It’s nighttime in Ferguson, Missouri. A man runs down the middle of the street, dressed in an American flag t-shirt, his hair flowing behind him in a street-lamp-lit wave. In his hand glows a bright red ember, a lit canister of tear gas. His arm is positioned to throw it back towards what is likely a line of cops in riot gear. There is a passion in his stance, a strength in his determined expression. This image became the iconic photograph of the Ferguson protests that followed the police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, stoking an ongoing protest against police brutality.

This photograph served as a visual focal point for much of the social media presence of Ferguson, but it came at a deep cost. The man pictured in this photo, Edward Crawford, died in 2017, allegedly of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. But those close to Crawford believed that his death was not a suicide, and there has been speculation on social media that his death was in fact intentional, and motivated by his activism. Whether his tragic death was a result of the psychological stress put on him by his position in the movement, or yet another racially motivated killing, it’s worth considering how Crawford’s presence in this photo contributed to his passing. His life as well as his presence in the visuals of the movement was valuable and important.

“This young man represented so much for Ferguson,” Missouri State Senator Chappelle-Nadal told the Washington Post in May of 2017. “On a global level, he is the individual who represented the Ferguson movement and what we were doing with our activism.” While this iconic image was impactful on an interpersonal and movement-based level, it points to photojournalism as a weighty practice that comes with deep questions of responsibility and morality.

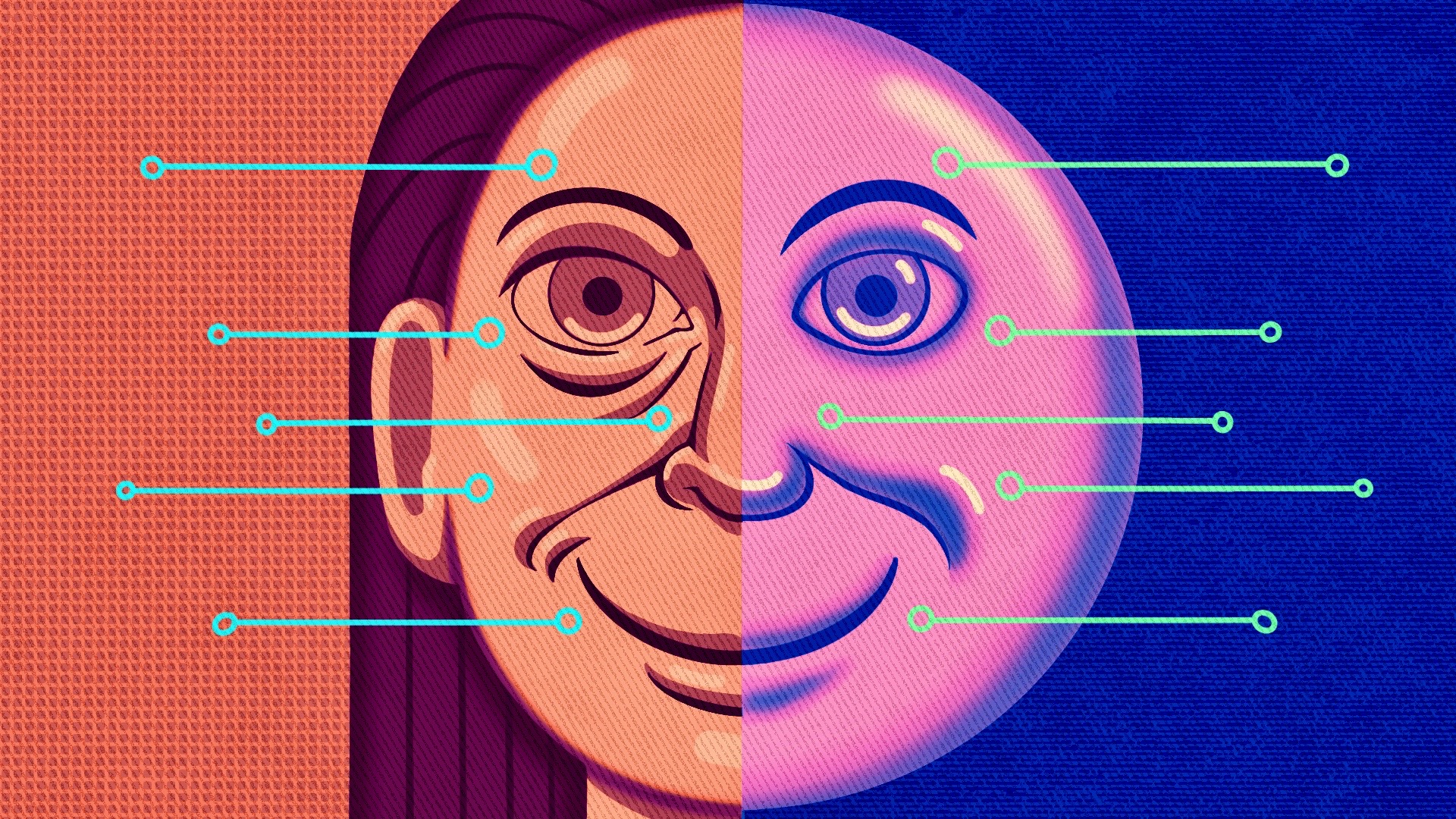

Artists are often fueled by a deep desire to express the truth of our present human condition. And in a time when the world is in deep unrest and protests flood streets across the globe, it can be understood that one would want to photograph these historic happenings. But what are the true costs attached to each of these images? Photos can be used to track down and target individuals, and with the increase of surveillance created by social media and modern technology, it is easy to find someone based solely on a photo of them. They can also invoke a strong sensory experience that many may find triggering, and can become easily exploitative of a BIPOC individual’s pain. When documenting a topic as sensitive as this, safety and care must be a top priority.

In May, the FBI tracked down a Philadelphia protester by examining a t-shirt she was wearing in footage taken by a television news crew, as well as Instagram photos of her allegedly setting fire to a police SUV. They then used Etsy and LinkedIn to match the protester with the footage, and arrested her. Photos provide evidence and may be the reason someone fighting against the police is led directly into their hands.

Besides potential legal repercussions, protesters in photographs can be found by white supremacist groups who wish to harm them. Activists — especially BIPOC activists — are often targeted for speaking up, and photos provide a paper trail of who is involved in the movement. When any identifiable mark is present, a pictured person can be found. Be it a tattoo or a bracelet, it is difficult to keep anyone truly safe once they have been documented protesting. One can use a blur effect, clone stamp tool, or a variety of other Photoshop procedures to obscure identity, but even this can often be decoded by experts.

Many people will take photos of actions, and having these images on your phone could possibly link you to certain movements and people, and still potentially provide this same dreaded paper trail. When saving photos one takes, if they simply want them for personal rather than posting reasons, they should be aware that those photos could still be accessed by someone you don’t want seeing them. This adds to the weight of the decision to take photos.

As with all important moments in history, documentation is inevitable. The way we document matters just as much as who presents and collects this documentation. With the Black Lives Matter movement, it is essential that we amplify their voices, and prevent white artists from turning their trauma into a portfolio piece. Black photographers have an authority on this topic, and it is important that white artists step down and lift them up.

Katia Jackson of Katia Sentry Photography is a Chicago-based photographer who documents the movement. “I’m a Black woman and I am a photographer, so it is important for me to share what is happening and share these stories,” she says.

But Katia also recognizes the importance of taking safety precautions when documenting the people involved in the movement. “I try not to shoot faces directly,” she says.“I just try to kind of position myself or get angles so that I’m not just shooting people’s faces, and I have had to like blur them or shade them.” She adds, “masks help conceal the identity of the protesters as well, because it shows the mutual respect we have for one another during the pandemic.”

Consent also comes into play when photographing protesters, and Jackson explains that during one-on-one interactions or whenever given a calm moment and opportunity to do so, she asks before taking photos of people’s signs and things of that nature. “I want to protect people protesting. That’s my top priority.”

Of course, even with these safety measures, nothing is 100 percent guaranteed to not be harmful, and it could be argued that protests are too dangerous to document at all. But this is an opportunity for Black people to tell their stories.“This is my freedom of speech … This is my movement, these are my people, this is my community. Nothing’s gonna stop me from being out there,” Jackson told F.

When documenting protests, it is important to consider how our images influence the movement. Others’ safety is paramount, and a camera can become a weapon. It’s a personal and individual decision, but when photographing protests, consider the harm you could do, what your voice means, and ask yourself if you should truly be behind the camera.

Great thoughts about how to photograph protests and protecting the protestors by not capturing their faces — great way to help protestors evade face recognition technologies