From Nov. 16 – Dec. 16, 2019, the School of the Art Institute (SAIC) held their annual undergraduate exhibition in the Sullivan Galleries. The first thing I learned was that I grossly underestimated how much time I should have budgeted for the event — with over 120 students’ thesis projects being honored for the fall semester, even spending a mere minute per piece would have taken two hours. The second thing I learned was that the exhibit grants more power to the viewer than it does to the artists.

The random lottery system for claiming a space in the gallery ensures that no artist was given priority over others, but it also caused the exhibit to sacrifice a cohesive theme among the menagerie of artworks, and sometimes diluted the presence of the artist itself. Smaller artworks were swallowed up by the wall’s expansiveness, and other installations were hidden behind corners of dead-end hallways. It was up to the viewer to be an explorer. No two pieces are alike, and we had the power to wander as aimlessly or as purposefully as we desired.

In truth, the experience can be overwhelming. A taxidermied snowy owl, a pointillist herrerasaurus, a white mouse rocking red retro glasses and sunbathing underneath an umbrella, a rock-climbing wall shaped like a starfish, a television playing Ann-Margret singing “Bye Bye Birdie” superimposed with pop culture memery like the video of the pika singing Freddie Mercury’s 1985 Live Aid “Ay-oh!”; DnD dice resting in a glass bowl of brown pebbles, knitted and crocheted clothes that the audience was free to wear, a triangular prism depicting citizens walking along floating circular platforms in the year 3020, a potted plant hanging upside down and its white flowers dipped in blood-red water . . . it took time to understand why I was drawn to certain pieces.

Two in particular caught my eye. Moises Salazar’s “Cuerpos Desechables: Detención” and Emilia Vidal-Hallett “stand%ing re%serve.” Some artists chose to leave a descriptive explanation for their art practice, others guarded their secrets — but these two pieces spoke for themselves. Every visitor to the Undergraduate Exhibition will have had something that connected to them, and for me, Salazar’s and Vidal-Hallett’s creative and instantly recognizable approach to crucial contemporary social justice issues appealed to me.

This is how I describe these pieces to you; this is how I respond to the SAIC’s Fall 2019 Undergraduate Exhibition.

Moises Salazar: Cuerpos Desechables: Detención

The human bodies of Salazar’s sculptures are adorned with bright colorful strips of overlapping paper, as if they are plastered with thousands of orange and green and red and blue and pink Post-It Notes. They are piñata people. But the colorful whimsy of their garments acts in stark contrast to their body language. There is no merriment: they huddle on the floor with heads bowed in exhaustion, some leaning against their neighbor for support and others wrapping their bodies in wrinkled tin-foil blankets. They look as if they are hiding from too many kids with too many baseball bats. The view from nearby windows is the city of Chicago — claustrophobic streets and looming skyscrapers — only serves as a reminder that their respite is temporary and insecure. They are the homeless immigrants; they are the desperate refugees. We are the onlookers.

Emilia Vidal-Hallett: stand%ing re%serve

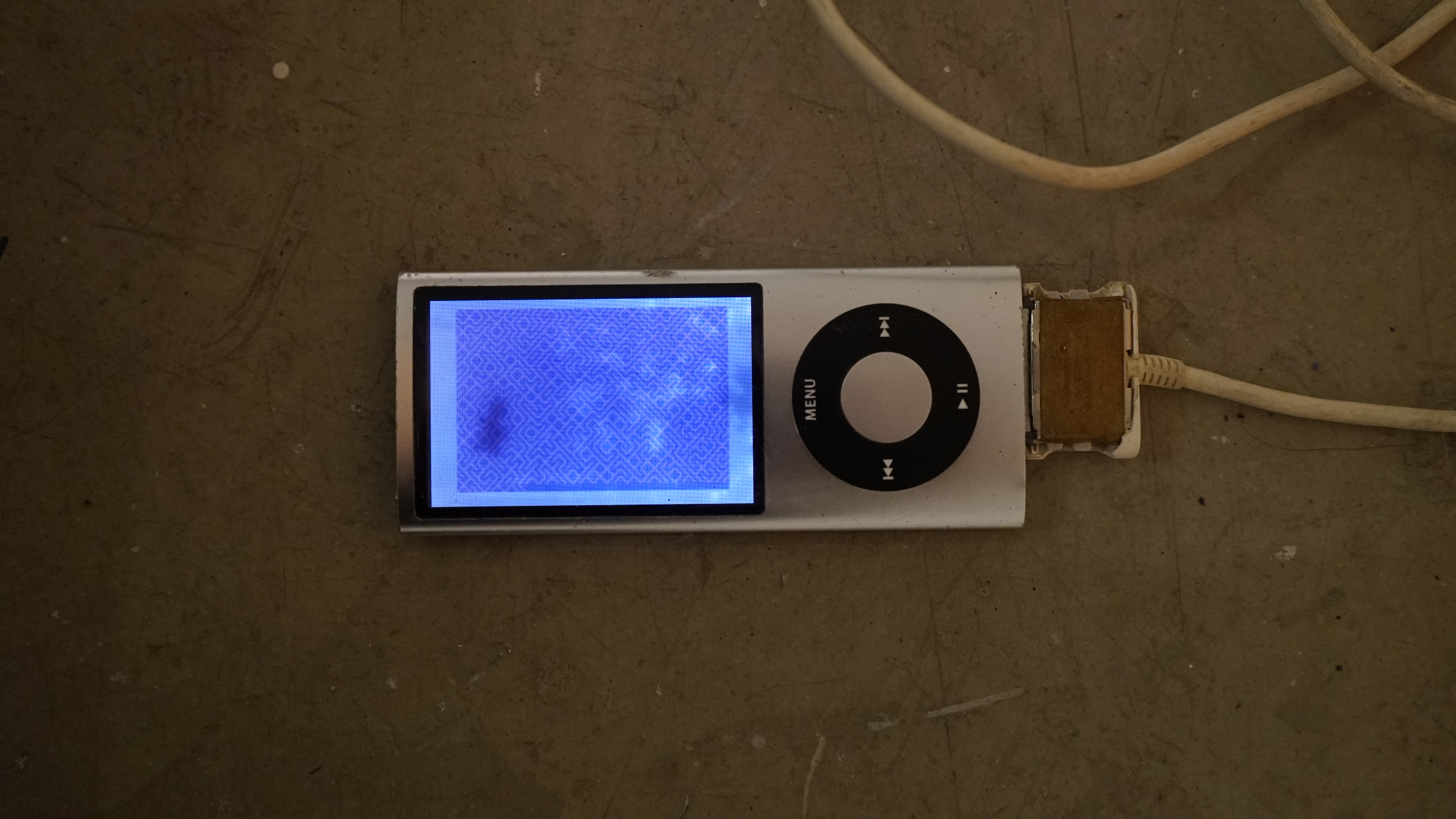

Vidal-Hallett’s installation piece features an electronic bird powered by archaic Apple products. Streaming from iPod Nanos and antecedent iPhones, charger cords connect to a central unit, which is plugged into a wall outlet. The tiny screens do not display a music playlist; the screens scroll through bars of broken code like long Tetris blocks stacked on top of one another. A video camera is pointed at the cords, and the nearby wall presents a close-up projection of the cords in alternating blue and green glows. The projection is a fixed image; a passerby waves their hand in front of the video camera, but the image does not change. Above these devices, a contraption suspended in the air churns its gears to lift the edges of a metal sheet — like a squeaking, squawking bird trying to take flight — uselessly but consistently flapping its wings, straining against the wires that hold it in place. It could be a statement on Apple itself and the mechanizations of corporate greed, but in truth, we know we feed into technological obsoletism. Without us, Big Tech has no power. Without us, the world would still be using iPod Nanos.