In contrast to my weak domestic observations, the artist Julia Fish has spent three decades developing an encyclopedic knowledge of her own home, a 1922 Chicago storefront. The last decade of Fish’s work is surveyed in “Julia Fish: bound by spectrum,” an exhibition currently on view at DePaul Art Museum. Based on architectural details, like floorboards and door frames, Fish’s paintings animate space with intimacy. The show is delightfully cerebral. Her work is most successful when deploying intricate networks of fragmented lines and geometric shapes, which are the basis of her abstraction. It struggles when the work succumbs to swaths of empty space, effectively centering on single letters of the alphabet.

Convoluted titles like “Threshold — Matrix: harbour [ spectrum : transposed ] / for E and L” provide the only key to the real-life architectural counterpart depicted in the paintings. All three of the “Threshold — Matrix” paintings are 30 x 70 inches, a size that pushes the landscape orientation to its limits and becomes technological — not a painting, but a server panel or widescreen cinema. In the aforementioned “harbour” piece, Fish uses oil paint and transfer chalk on a rich grey ground that resembles a lush chalkboard. Marks appear Rainbow Brite on top of it, and little blips of line occasionally meet in a corner or assemble themselves into Tetris-like forms. In the midst of regimented lines and hexagons, Fish deploys a painterly style with the leftover residue of chalk, apparently smudging it away with a finger. It is captivating evidence of the artist’s hand in works that typically revel in showcasing her incisive eye.

The color of the marks in “harbour” moves through a spectrum of hues from cool blue to yellow, mimicking the mutability of natural light. Similar to this tidal refraction, Fish’s paintings are often irreducible to one vantage point. I follow the implied lines and imagine the seams of hardwood flooring, or the space between a baseboard and the floor, but the forms are resistant to interpretation. Instead, I am left contemplating the relationship between me and someone else’s home as an extension of painting’s figure-ground conundrum. Though it originated in Gestalt psychology, figure-ground no longer refers solely to the flickering that occurs between two profiles and a vase; rather, it signifies a perennial existential question about the relationship between an individual and a community, or an idea and its context. Viewing Fish’s paintings feels like trying to read a language of which I have little knowledge: Nuances in syntax evade me, but there is an expressiveness to the grammar that grips my attention.

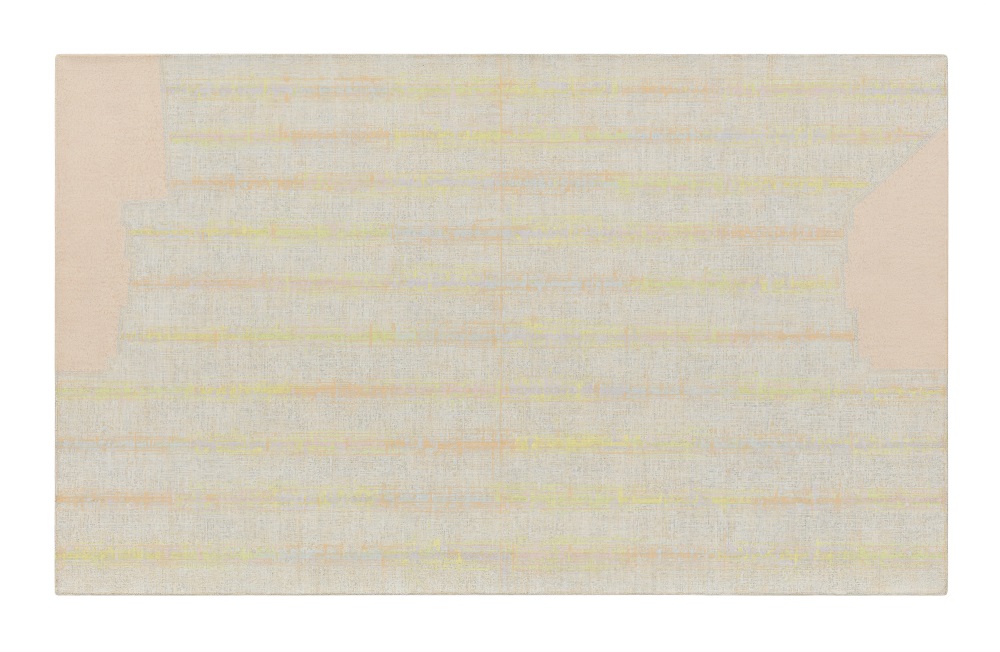

Also on display are six of Fish’s “Threshold” paintings. The wall text informs viewers that works in this series are “1:1 scale and based on the shapes created by doorjambs, doors, and flooring, such as wood, linoleum, and ceramic tile, as if looking from directly above.” Like nearly all the paintings in the show, each one is at least one-and-one-half times as wide as it is tall. Though they claim to have a direct relationship with reality, due to their dense patterns, which are surrounded by placid pastel colors, they appear to exist somewhere between an architectural plan and a microscopic image. Each piece depicts one shape that is bisected and rendered using two distinct systems: presumably, a description of one room as it meets another.

The show includes studies for the “Threshold” paintings, small works in gouache on paper. The studies depict thick shapes with contours, like a capital seriffed letter “I,” made up of a square grid of smoldering, closely related colors. It is the layout of a threshold that serves as the foundational shape for the paintings, in which Fish adds other architectural details. I found it difficult to abandon the association to a typeface design, especially because each composition leaves a hefty white border. What I typically find enjoyable about a study is witnessing an artist’s early process. The idea is still flexible when it is first transcribed into form. In “bound by spectrum,” the “Threshold” paintings are sophisticated and candid, while the “Threshold” studies are one-note.

Prior to seeing this exhibition, the paintings I was most familiar with by Fish were the playful but focused recreations of tile flooring made at the same time as her 1998 site-specific installation of die-cut vinyl on top of floor tiles, called “floor [floret].” The tile works are intriguing because they invoke seemingly contradictory painting conventions, offering themselves up as representational, but executed in the style of all-over abstraction. The wall text introducing the current exhibition declares that these paintings are “leveraging abstraction in service of representation.” This strikes me as imprecise. The text could easily flip the hierarchy, stating instead that the paintings use representation in service of abstraction. Fish’s work defies reductive categorization. The paintings do not yield easily, and it is this very stubbornness that I relish.