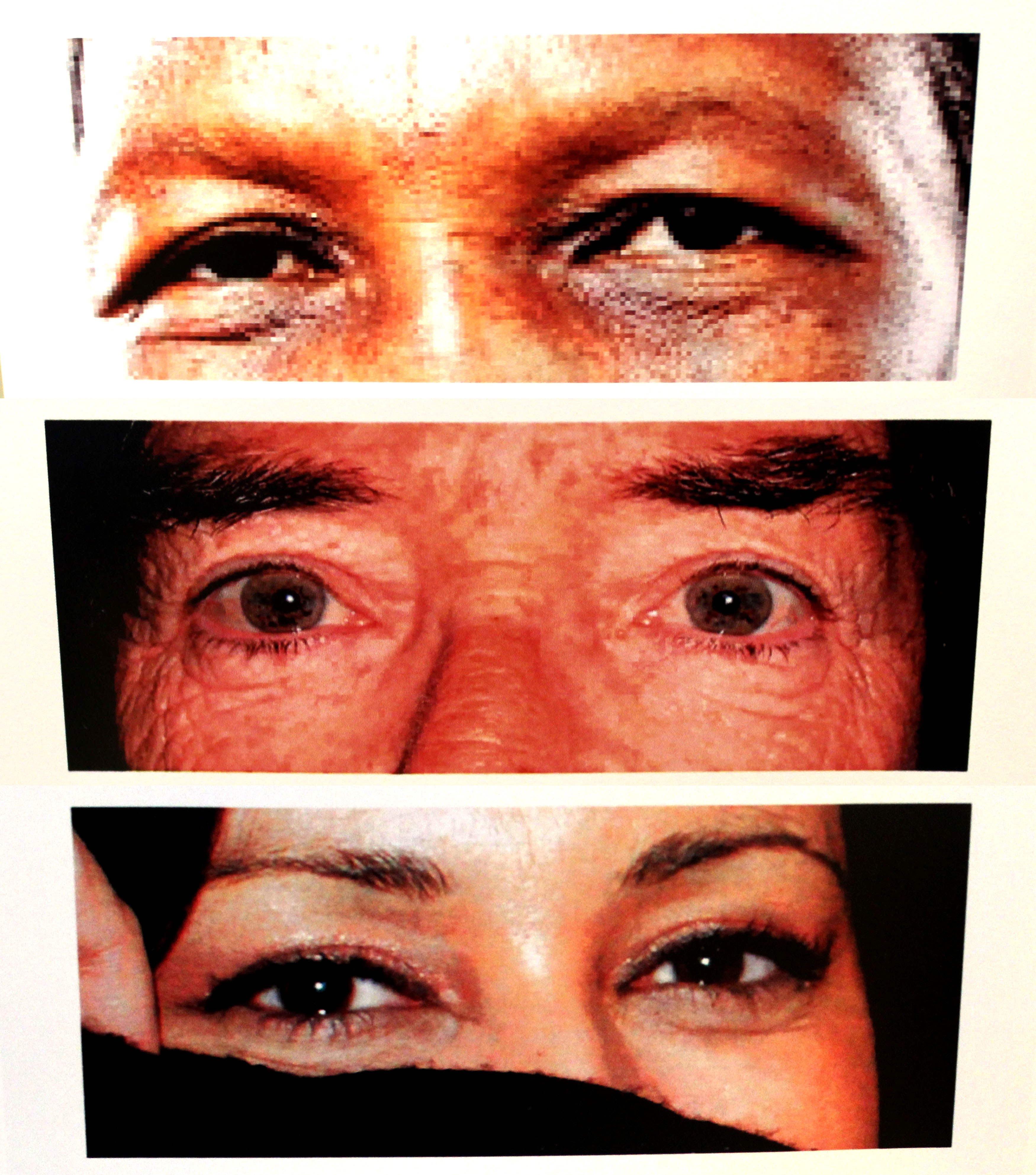

Several dozen letter-sized sheets of computer paper hang on filing cabinets around the perimeter of the Joan Flasch Artists’ Book Collection and Archives reading room, in a recreation of Yoko Ono’s 2013 “Arising” installation. The papers contain images of the eyes of women who have contributed written testaments of harm — young women, women in glasses, women with wrinkled eyes, some with stated first names, others without. The testimonies are handwritten and typed in a variety of languages. Some hang crooked by their magnets, jostled from the opening and closing of metal filing cabinets.

In the project’s original iteration, “Arising” invited women of all ages, across the world, to send Ono a photograph of their eyes and a written testament of harm they had experienced solely for being a woman, and/or a clothing item for the accompanying installation. To this day, the exhibition is considered ongoing and participatory.

When I enter the reading room, the small space is already filled with a class of students. A projector screen descends, and a video starts. The sound of strumming guitar chords and Ono’s loud vocal trembles fill the room. I recognize a track from Ono’s 1994 album, “Rising,” which she recorded with her son Sean. In 2013, she told an interviewer for Whitehot Magazine that she instructed her son and his bandmate, both teenagers at the time, to play a single, repeated harmony throughout the entire track. There was no editing and no rehearsal. She focused on producing sounds she felt only women could make. The result, she said, is “based on the voice of a woman who suffered a lot. That woman is me.”

Sharing the space with a class, I’m not sure if Ono’s yowling is welcomed or considered a distraction. Beneath the sound, a professor quietly tries to teach. A pile of silicon women bodies burn on the screen. Watching feels voyeuristic, as the gaze of the camera shifts around the pile. Are these my eyes? Did I set this fire?

Soon, the bodies are engulfed in flames, and Ono’s voice becomes more powerful. She grunts: “Have courage, have rage, we’re rising,” the ashen bodies now a crumbling mass of anonymous limbs, breasts, and torsos.

A pile of donated clothing items sits on the floor in front of the screen. I spot folded Levi’s, a lightly used shoe with the shadow of bare feet barely visible on the inner sole, and plaid dress pants soon to be buried beneath something else. A pile of crumpled bodies, a pile of clothes — what does a pile signify? It all feels too small. I wish the pile took up more space. I wish it climbed so high it touched the ceiling. I wish there were so many contributions that cardigans, blouses, and slacks tumbled out into the hallway blocking the entrance to the room altogether. A student asks the professor what the pile means. She replies: “Lots of bodies, lots of chapters, lots of evidence.”

I quietly walk the room, staring into the eyes, moving around other people who, in trying to utilize the space, are ignoring Yoko Ono and ignoring the eyes. The room’s setup makes the art inaccessible. Some eyes are behind tables and chairs, out of reach during my visit. Frustrated, I reread the ones I can get to several times. Are the eyes seeing me or am I seeing them? Are they seeing me seeing them?

I wish these women’s eyes were to scale; they feel too small. There are women whose eyes are smiling. Some women are looking up or looking through me. I wish I didn’t have to look down at them. I wish I could meet their gaze. I imagine there are so many eyes they run out of paper and ink. I imagine the eyes are the size of hot-air balloons, flying through the sky. I imagine the number of testaments grows so big, so tall, that they hang from power lines, line the city streets, clog up storm drains until they can no longer be ignored.

The professor is now talking about artist book paper types, hidden pockets, vellum, and envelopes. I’m unsure if Ono is belting a lament, a ballad, or a rallying cry. I feel distracted in this space, the eyes disjointed from the video screen, the video screen disjointed from the pile of clothing on the floor.

I am invited to contribute my own testament. I look into the eyes of one woman who writes: “How can one measure the harm done by traumatic experiences?”

Where would I start? How would I fill my A4’s worth of blank white space? Which filing cabinet would my story be stuck to? And when the exhibition closes, will my page be dumped into a recycling bin? Will my eyes travel to the curb, waiting patiently for pickup? Will they be mashed and shredded by pulpers at the recycling mill, decontaminated and pressed into a brand new ream of white computer paper? Will another set of eyes take the place of mine?

This recreated installation is billed as a “[transformation of] a space normally reserved for research and teaching into a meditation on human experience.” While the willing participation of women from around the world to reveal some of their most painful, dark, and vulnerable moments is the essence of “Arising,” what gives it its power is the trust involved in telling the truth. The way we decide to publicize these intimate testaments is crucial. Unfortunately, these women and their truths fade to the background in this small, multi-purpose room. Transformation implies metamorphosis. It demands more than alteration, and certainly requires more than computer paper stuck to filing cabinets with magnets.