Wrightwood 659’s first show devoted to queer art, “About Face: Stonewall, Revolt and New Queer Art,” is an ambitious new exhibition that aims to to challenge how we think about gender, sexuality, and identity politics. Curator Jonathan David Katz, PhD, who is Visiting Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at The University of Pennsylvania, describes the show as “about our common humanity.” But although public programming accompanying the exhibition has provided a platform for a diverse group of artists, the exhibition itself is overwhelmingly dominated by male artists.

The show commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, a major catalyst of the gay liberation movement. When police violently raided a shabby bar called the Stonewall Inn, located in Greenwich Village, New York City, on June 28th, 1969, the queer community responded with protests and mobilization. There had been recurring police raids on gay bars in New York City before this, but this raid started an uproar in the queer community and is historically considered the first time queer people fought back in large numbers against authority. But Katz wants one thing known: Stonewall wasn’t the start of queerness. In fact, the exhibit challenges what Stonewall actually represents. Queerness had been around for a long time before Stonewall, but Stonewall was a catalyst for larger themes within the queer community that were long repressed by most of the community: sexual freedom and public displays of homoeroticism, which are recurring themes throughout each chapter of the exhibit.

Taking place in Chicago’s Wrightwood 659, the show is embedded in the work of art that is the architecture of Tadao Ando, a Japanese “starchitect” whose designs play on the use of natural light and building as sculpture. It takes up all four floors of the building, with sections devoted to the five curatorial categories that Katz has organized the art into: “Transgress,” “Transfigure,” “Transpose,” “Transform,” and “Transcend.”

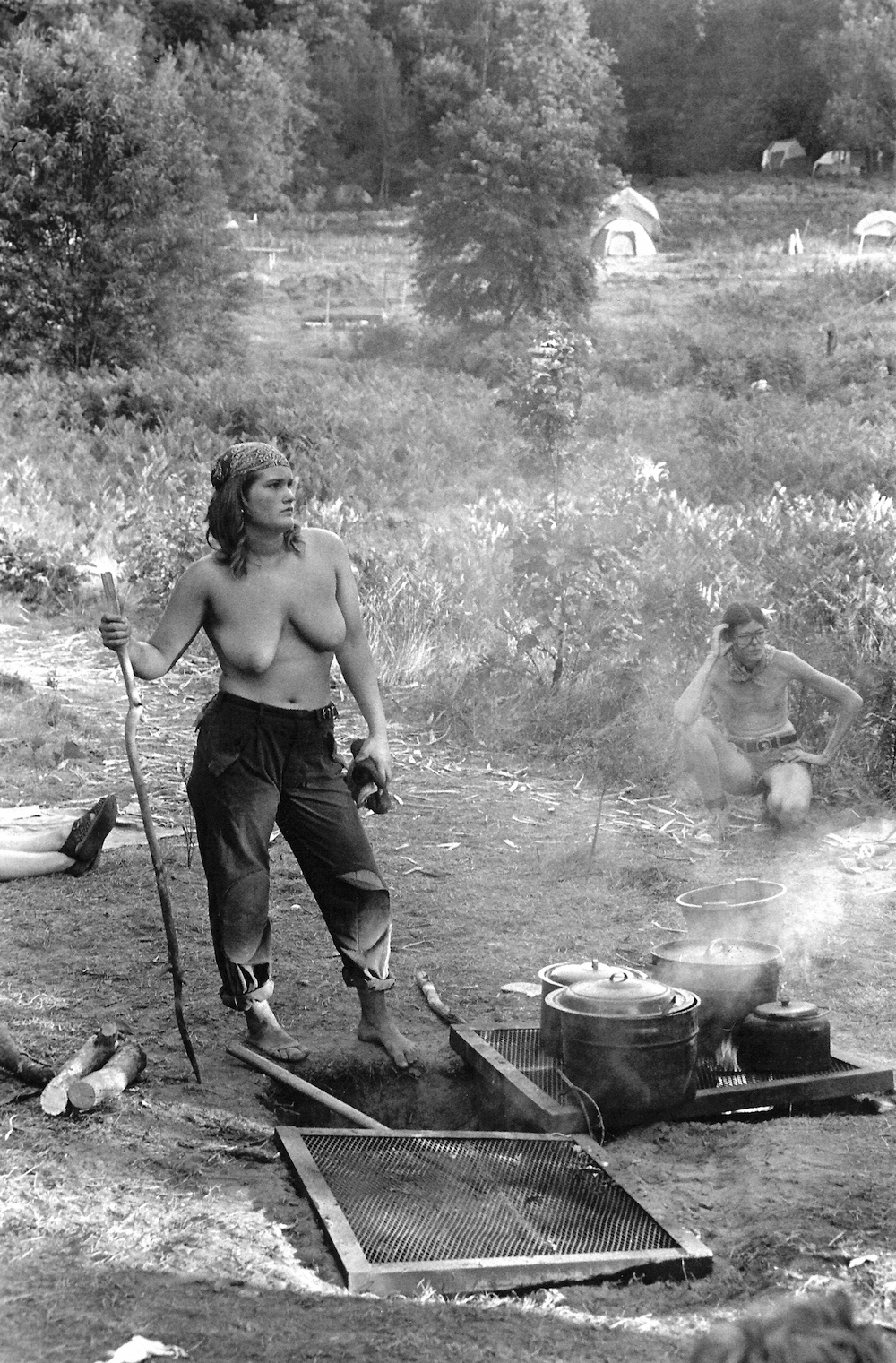

In “Transgress,” which means to go beyond the bounds of, Joan Biren’s photographs of happy, natural women in rural, peaceful environments stands out as a powerful statement of what it meant to be a lesbian in the 70’s and 80’s. Biren’s work is a delightfully revealing group of photojournalistic portraits of female couples and groups of friends from an earlier era. This is something younger generations like me can appreciate, given that most of us have never seen queer narratives from the 70’s and 80’s. Biren’s work is also special in that her subjects are not afraid to show off their happiness, sexual freedom, or loving disposition towards their friends or significant others. Looking at each of the photos, there’s a feeling of being transported to a peaceful place where anyone’s fluid sexuality and gender expression is supported, and expressing one’s sexuality or gender is freeing instead of oppressive. In one photograph, women stand on a porch, talking, laughing, and having a good time, wearing whatever they please. In another, a woman stands topless, wearing worker jeans and sawing a slab of wood. In another, a lesbian couple peacefully embrace each other on the grass with their eyes closed, facing each other. Joan Biren’s work is remarkable; it reminds us that the queer community as it was then had taken on similar aspects of today’s queer community, and queerness existed long before it took on a different name. It wasn’t accepted, but they existed in plain sight. They loved, they existed, and they conquered those times by being in the company of those who accepted and adored them, going beyond the bounds of heteronormativism.

In the subsection titled “Transfigure,” which means to transform into something more beautiful or elevated, Zanele Muholi’s large-scale black and white portraits depict the multiplicity and complexity of the artist’s self. Muholi’s practice shows how queerness is multi-layered, dealing with more than same-sex attraction. In one self-portrait, titled ”Phila I, Parktown,” Muholi looks at the camera, wearing dark disposable gloves that have been inflated and fashioned into a headdress. The differing textures of these gloves – some are completely inflated, while others are starting to wrinkle – suggests a material other than what “balloons” normally conjure. This image is one of more than 90 self-portraits in their practice as a whole that depict the artist’s various personas. Muholi has said their work is “visual activism” aimed at exploring identity in relation to the LGBTQ community in South Africa. Muholi’s work has an immediate visual magnetism because of each photograph’s high contrast values, especially the subject’s richness in relation to its stark background.

In “Transpose,” meaning to cause two or more things to change places with each other, Sophia Wallace’s photography challenges ideas of masculinity by showcasing narratives of gender expression that point to female masculinity and male effeminacy. In “Untitled (Truer, No. 11), 2008,” Sophia captures a moment showing the artist with her partner in their bedroom. Her partner is lying comfortably on the bed while Wallace sits on the floor with her arms and head resting on it. The couple looks up at the camera with a relaxed confidence. Their room, a place of intimacy, is framed to include only a bed; it’s a touching photograph that communicates the story of a queer couple in a small apartment.

These queer subjects, as photographed by Wallace, confidently state their experiences and occupy space in the world. In “Untitled (Modesty),” 2010, sad blue eyes stare at the camera, a man wearing a blue niqab (a veil that covers the face, showing only the eyes) stands in front of a blue backdrop. It’s a melancholic piece that is undoubtedly captivating, but what makes it so unique is that we quickly become aware of how the niqab doesn’t pertain to the subject, as he is standing shirtless with a headdress that’s meant to accompany a fully covered outfit. Nonetheless, seeing a shirtless, masculine-appearing body juxtaposed with the niqab and his gentle disposition sets off a curious and evocative form of communication between the subjects and its audience, especially when the photographs’ subjects are to scale and looking at the camera (or the audience). Experiencing Wallace’s photographs in person is like taking a deep breath of fresh air in the morning and looking at mountains covered by lush forests from your front porch – it’s refreshing, pure, and absolutely stunning.

In “Transcend,” meaning to go beyond the range or limits thereof, Gail Thacker’s 665-type Polaroid film images portray her surroundings, friends, and lovers. One of these is performance artist Mark Morrisroe, pictured on his hospital bed before he died of complications of AIDS. Morrisroe gifted her a large quantity of the 665-Type film before his death; the film type was initially released in the late 70’s as an industrial version of the Type 100 pack film. Thacker altered the polaroids by sealing them in plastic bags, unrinsed for weeks or months at a time, and sometimes leaving them outside, allowing the pictures to produce unexpected but mesmerizing tonal shifts as they aged. These polaroids, as a result, undergo a process of degradation which parallel the effects of the HIV infections many of her subjects lived with. The grittiness and fast-aging effects that the chemically distressed polaroid images portray opens up an emotional quality to accompany each subject’s personal battle with what was then an untreatable disease.

As a queer non-binary individual, I can appreciate the grand gesture of including over 40 queer artists in a very special place and work of art by Tadao Ando, but I did not sense the representation that I expected from this show. White cisgendered gay men have had ample representation within the queer community, and in some ways within the larger art community. In a study of 820,000 exhibitions across the public and commercial sectors in 2018, only one third were by women artists. And a data survey of 18 major U.S art museums found the artists represented in their permanent collections were 87% male and 85% white. When you’re preaching inclusivity, in any situation, the results should point towards inclusivity of all kinds, not just sprinkling a few queer women or transgender artists here and there like salt on a bland dinner. If it’s anything that this show confirmed, it’s that the queer art world, as curated by Katz, is still very much a man’s world.

It’s a shame Jonathan David Katz didn’t include artists who aren’t white cis-men like Rashayla Marie Brown, Patricia Cronin, María Elena González, Harmony Hammond, Sharon Hayes, Deborah Kass, Greer Lankton, Brianna McIntyre, Alice O’Malley, Keijaun Thomas, or Del LaGrace Volcano in addition to the few artists mentioned in this article. That would have been a great show! Especially if the cis-men presented cut across generations, nationalities, religious backgrounds, and included men with HIV, men who embraced the drag community, Asian, Black, First Nations, Latino, and South Asian men in a genuine effort to reflect a representative sample of the queer spectrum in a finite space. Maybe we’ll get to see a show like that one day!