I was thinking about John Cage’s approach to curating at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

In order to review the MFA shows (the high-residency MFA, on view April 29 – May 15, the Low-Residency MFA show, July 11 – 28) I printed out the name of every artist and cut them into strips.

I piled the names into the palm of my hand and pulled nine from the pile.

Then I spent six minutes looking and thinking and scribbling in the presence of each artist’s work.

Then I spent an undelineated amount of labor and time pushing the scribbles into six reasonable (?) lines per artist.

Criticism, by definition a practice of judgement and valuation, has here been ceded to chance.

Celeste Cebra (MFA Photography, 2019)

In these four large, appealing photographs, minimalist trash and household items are stacked and balanced into precarious, fairy house-like structures.

The palette is polar: mostly white and and translucent, with darts of sudden color.

There’s a wavy glass brick and plastic straws; empty Modelo bottles, their gold labels glinting; the cover of a light switch, then miscellaneous plastic and organic objects — a claw-like pinecone or some other dried spine, a husk (corn?) fluted into a small purple vessel (a lighter?).

There is a progression between the four images — objects are added from left to right, then crushed and encased in ice — but I want there to be more rules for the progression.

And I want the structures themselves to be bigger and more complex, a la Rube Goldberg.

But this is one of my flaws, always desiring something on the brink of failure.

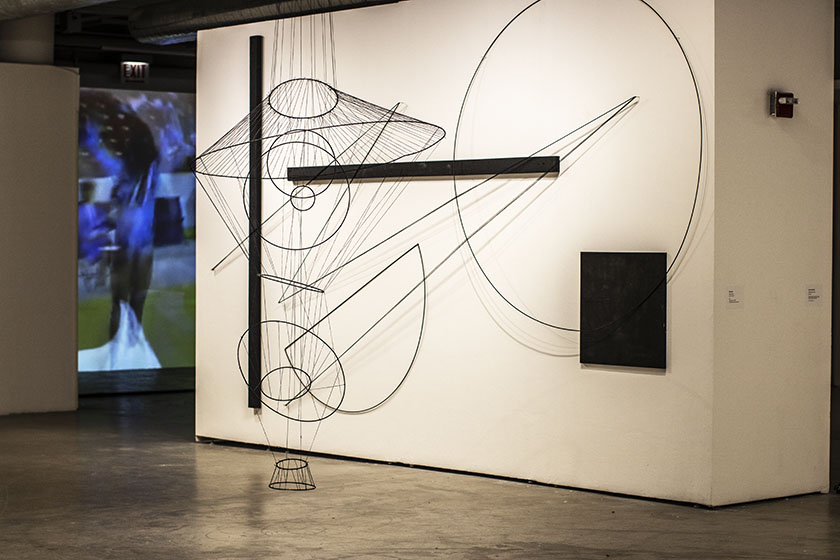

Nneka Kai (MFA Fiber and Material Studies, 2019)

The shared language of these two sculptural pieces is the lines of their taught black string and their clean geometric forms.

One sculpture, made of different sizes of wire hoops, connected by vertical black threads, hangs from the ceiling.

It’s like a lapsed birdcage turning into a hoop skirt, or a hoop skirt flipping into an enormous lampshade, or one wonderful model of the universe.

Or maybe a spidery take on a costume from Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet.

The wall piece, which clings flatly to the wall, the threads running between the shapes, is significantly blander.

It’s like a belated Bauhaus experiment commissioned for a bank lobby.

Soledad Fátima Muñoz

Displayed beautifully in an arc of windows that looks out onto State and Madison, Muñoz’s cascade of woven faces emits a low buzzing from the speakers that encircle them.

The faces are cotton and copper wire, and they are so beautiful that I could have laid down and lingered there forever.

One medium (the photograph) translated into another is the lossiest; the faces are made of static, and they have 70’s moustaches and center parts.

They are the disappeared, hanging from the ceiling.

But, beauty can be a problem: too many components risk distracting from the historical context and intended meaning, and that explanation — the connection between the University of Chicago’s economics department and U.S.-backed Chilean dictator Augosto Pinochet — happens in the wall text, rather than in the work itself.

The gallery attendants bark and shriek on the other side of a gallery partition, and it is amplified; is this a monument or a warning?

Kurtis Kujawksi (MFA Painting and Drawing 2019)

Three large oil paintings showing quasi-mythic scenes: a tree-person looming over two lovers; a dancing couple adrift on the hem of an orange dress; a sailor gazing at a jolt of light in a storm.

Each painting is accompanied by a song written and performed by the artist, which plays from overhead; the premise could work eventually, but here it’s gimmicky.

The blue outlining on the pink bodies is beautiful, and the black boots are shapely and fine — you could dissolve everything else, but keep those boots how they are.

The compositions were invariably slightly off, and the colors looked straight from the tube.

I am not convinced that all these brushstrokes know what they’re doing, besides making a surface look painterly.

It would help to treat canvas like a finite resource, a rare earth mineral that could at any minute run out: it is okay for paintings to be small and executed with great care.

Efrat Hakimi (MFA Painting and Drawing 2019)

There are two barriers, like the metal ones around the base of the monument, but here they are made of paper.

There is an embossed gynecological instrument.

Marion Sims, father of modern gynecology, experimented on enslaved black women whom he kept chained in a stable in the back of his estate; but there are still monuments to honor him, just as there are still monuments to Christopher Columbus, Thomas Jefferson, Robert E. Lee, Frank Rizzo, and so on and so forth.

Whose bodies were embossed, scarred, infected, disposed of, and forgotten in medicine’s name?

A two-channel video, which captures the removal of the Sims monument in New York’s Central Park, lingers beautifully on all the mundane details of the task: closeup shots of workmen’s boots as they sweep the dais, the statue’s head covered by a quilted cloth as it drifts away on the bed of a truck.

The negotiation of history and controversy is here made mundane: after the protests and the public hearings and the op-eds, there are the newscasters practicing their lines and the sound of the drill saw as the statue is removed from its base.

Betelhem Makonnen (Low-Res MFA 2019)

The work hovers around self and identity and perception, but when will it come down to land?

In a video, the artist stacks mirrors against the wall, repositions them, examines their reflection.

The use of mirrors is mildly interesting, but the studio is overly recognizable as a studio, and it’s hard to compete with other artworks in the mirrored artwork hall of fame (Cannupa Hanska Luger’s mirror-shields at Standing Rock, Joan Jonas’ various reflective performances).

The photographs, of the artist’s earnest and puzzled face, are printed on clear film, displayed rolled into a tube and backed by a mirrored ground.

But the construction is too cheap and fast, or not cheap and fast enough.

The artist’s book, at the front of the exhibition, is an interesting weave of memories from the artist’s childhood in Ethiopia with snatches of theory.

Milo Carney (Low-Res MFA 2019)

Why did the artist do this?

A chain link fence with ugly and unredeeming vinyl banners tacked to it cuts off a corner of the gallery.

So what?

The banners, apparently drawn up in MS Paint in 6.66 seconds flat, vaguely reference capitalism (images of storefront signage, images of price tags) in the least compelling ways possible.

They apparently aspire to be both socially relevant and flippant, but with phrases like, “Curiosity killed the cold turkey over spilled milk,” “No such thing as a free lunch,” and “Everything is happening at the same time,” they fail at both.

What can you do that Mark Bradford or Andreas Gursky has not already done?

Alison Kudlow (Low-Res MFA 2019)

First there is a fantastic ceramic and glass crater the size of a bathtub, with rings like the rings of a tree or a pit mine.

Then there are forms clustered on floor: stacked white porcelain forms like cow skulls.

The work is about time and mortality and grief and the passing of the artist’s younger brother.

There are glass pieces hanging from the ceiling.

They show their own weight beautifully, like plastic bags holding water hung from the ceiling by each corner.

For work about the entropic (and fairly picked-through) subject of time, the artist exercises a lot of control over their mediums.

Daniel Salamanca (MFA Painting and Drawing 2019)

The artist is one unit of the “Carbon Copy Collective,” a group of seven students in the Painting and Drawing Department who intermingled their works in a larger space in Sullivan Galleries — an admirable but somewhat jumbled attempt to build a collective lagoon in the swamp of cubicle-like solo projects.

There is a small red projection of a cityscape.

It is the sunrise, in real time, I think.

For a long time nothing happens, then “6:47” flashes on the screen, then, “The world is going to end on a red flood.”

My interest in its quiet beauty began to dissipate when I recognized the view as shot from an upper floor of the MacLean building, where the department’s studios are located.

Across the room, above a doorway, a charming, winking little painting that resembles the ubiquitous red and white “STAIRS” sign, but this one, instead, reads “STARS.”