27-year-old Catherine White says it’s normal to think about our bodies and their mortality. “Occasionally you might find yourself thinking, ‘Wow, one day I’m going to die,’” she says. Behind her, on a bench cluttered with stacks of paper, sits a cluster of bones with metal rods sticking out of them. “But I don’t think this place is a very gory institution,” she adds. “In fact, sometimes our visitors wish it was more gory.”

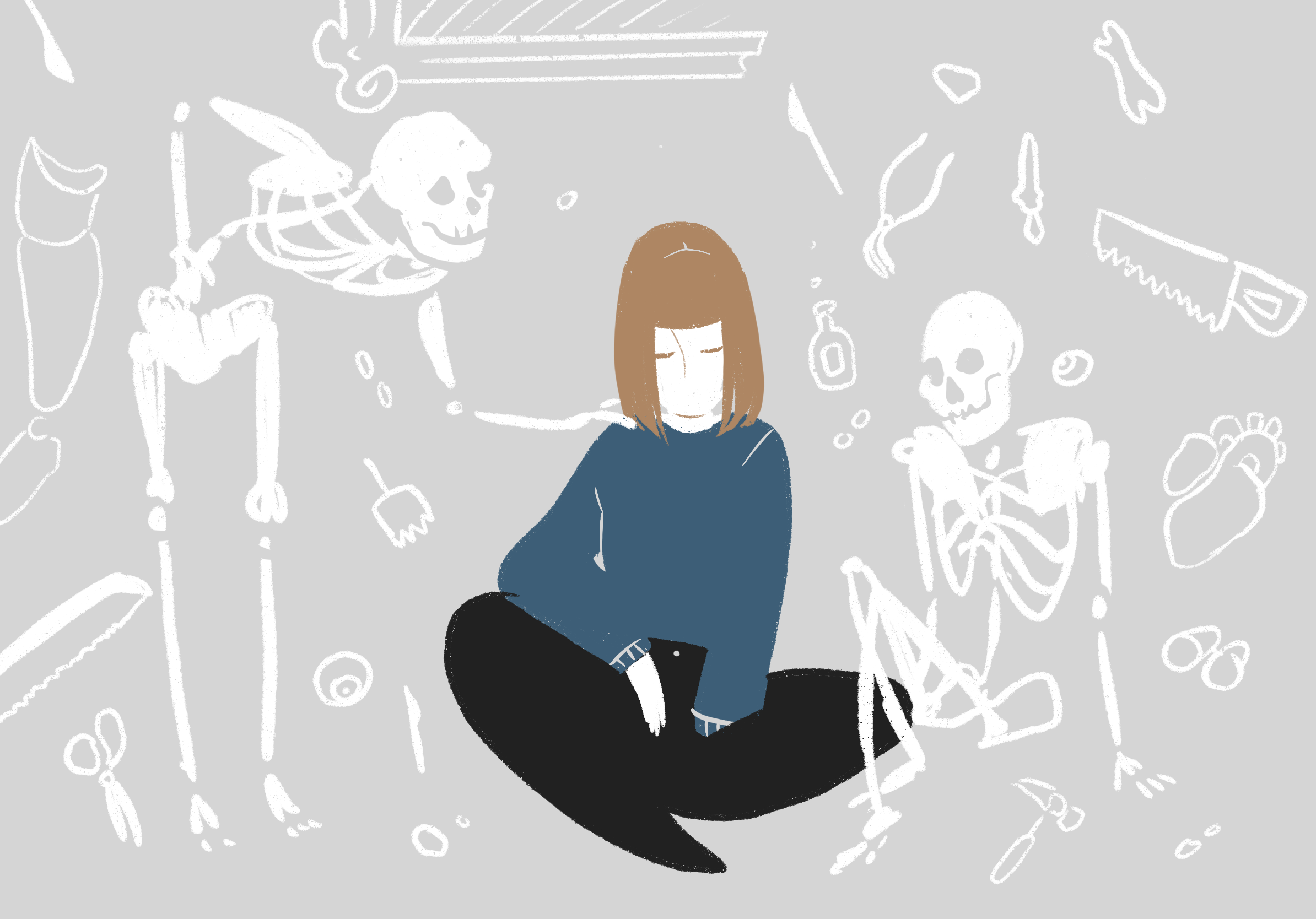

White, Assistant Manager of Education and Events and one third of the full-time staff at Chicago’s International Museum of Surgical Science, sits cross-legged in the office she shares with the rest of the museum’s employees. The small room is academic in a way that feels prestigious but ominous, like a haunted boarding school. Papers and books are everywhere — shoved on top of each other on shelves, tossed onto empty desks, stacked on the floor. The sound in the room is dampened by the worn carpet, though not enough to keep the hinges on the room’s heavy wooden door from shrieking whenever it is opened.

The museum feels this way, too. It resides in the Eleanor Robinson Countiss house, one of the few remaining lakefront mansions in the city. It was originally modeled after Marie Antoinette’s 18th century playhouse — marble staircases, stone fireplaces, and enormous French windows spilling early afternoon light onto the polished floors. One could imagine living here, entertaining here. A gloved hand trailing down the banister, high heels clicking on the cold stone steps.

Like all once-grand houses that have been gutted and had their function changed, the Eleanor Robinson Countiss house feels ghostly now. Whisperings of its former life linger in every room. What could have been a parlor is now empty save for six looming statues dotting the perimeter of the room — pioneers of surgical science frozen in place and forever staring. What was once perhaps a bedroom now houses a case of artificial eyes; in another bedroom, there’s a skeleton of real human bones. The grand, silent hallways on each of the mansion’s three floors have been decorated with massive paintings showing gruesome scenes of the early days of surgery. In one, a pale, naked man is held down by four other men as a fifth saws his leg off.

The mansion’s multiple floors make it easy to find oneself alone in these rooms, with the loud echo of one pair of footsteps implicitly encouraging each visitor to step more delicately, should someone — or something — hear them. It’s difficult to remember that this space is a museum and not the home of a late eccentric who died under mysterious circumstances. Walking through the mansion feels like a live-action game of Clue, like it’s the visitor’s job to deduce in what room and with what object someone was brutally murdered.

Catherine White is unbothered by all of this. “It’s a part of life, right?” she offers, coolly. “If we can be a place where people can sort through those ideas in a healthy and educational space, I think that’s good.” Back in the shared employee office, her desk is comparably neat— some trinkets, a tube of hand lotion, her computer. A shelf sagging under its weight threatens to collapse above her.

As the educational coordinator, Catherine works with student groups, guiding children through the museum on tours and conducting demonstrations with them. Catherine mentions that the most popular educational program outside of the tours is the amputation demo. In it, two children are called up to be the doctor and the assistant, and a third acts as the patient. The children then use a replica of a Civil War amputation kit to mimic what a battlefield amputation would be like.

“Are you washing your hands at that time period? No. Are you washing your tools at that time period? No,” Catherine says, her voice changing: educator mode. She begins listing the kinds of things that are brought up during the demo: “How fast was a surgery done? Back then, it would just take 5, 10, 15 minutes. What does it mean if you go faster? You’re not being very careful. Maybe you’re making a mistake, maybe you’re shredding the muscle or hitting an artery.” She says all of this easily, like reading a grocery list aloud.

She adds that the kids love it, too; they think it’s cool. “I think it brings history to life in a way that’s exciting,” she offers. To her, this museum serves the same purpose that every museum should: to teach visitors in a way that feels both visual and immersive. And sometimes, seeing something shocking, even unsettling, can be an effective way of learning.

Catherine experienced this at a very young age. “I’ve always been a big museum dork,” she says. She started going to museums with her family at age four and was smitten from the start. Her parents were members at the Field Museum, among others, and would take Catherine and her two brothers to members’ nights. Her first museum memory was when she was four or five at a 1996 exhibit on bats at the Field Museum. “I remember seeing what, to me, was a giant bat replica that was about the size of me. It really scared me, but it also really drew me in,” she recalls. “I was like ‘What is this?! I’m scared, but I want to learn more.’”

She would have her birthday parties at museums, sleepovers at museums. She and her family would visit museums on every trip, and any museum was a viable choice — anything from the Art Institute of Chicago to the Spam Museum. Catherine mentions one collection in particular: a conglomeration of hundreds of types of nuts from around the world, collected and curated in the home of a woman known as the Nut Lady. After the Nut Lady died, one of Catherine’s undergraduate professors took over the collection and continues to preserve the small museum.

“I like learning, and I like school,” she tells me. “I was one of those kids who was like, ‘I want to be a ballerina, explorer, writer.’” That’s not surprising; she seems like the type. It’s easy to imagine her like that — the kid who wasn’t afraid to pick a cicada carcass off a tree to inspect it, to the abject horror of the other children.

Working at the Museum of Surgical Science is White’s first job out of graduate school, and a job she started the day after defending her thesis (she graduated from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Art Education program in 2018). She’s careful not to say if or when she might leave this museum, but she says several times that she doesn’t want to shoehorn herself into one particular discipline within museum work. “I’m very afraid of stagnating intellectually,” she admits. “I don’t love just sitting down and reading a book and not having anyone to talk to about it.”

Catherine mentions that she didn’t come to this museum with prior knowledge of surgical history, but that doesn’t seem to matter. She thought it was interesting. That seems reason enough. And talking about the subject, Catherine is enthusiastic to the point of sounding defensive. “People think museums are boring, but they’re not. They’re fun,” she says, somehow combining sincerity with defiance. “Where else would I learn about nuts? I guess I could Google it, ‘different types of nuts in the world.’ Or is it more fun to go see thousands of nuts in someone’s living room?”

Seeing her in this space — legs crossed, arms crossed — it’s easy to feel guilty. To feel guilty for flinching when she explains how the Field Museum let her touch the spiders on members’ nights. She glances back at the pile of bones behind her. This deeply, deeply haunted museum is also incredibly fascinating. She’s right: People do want to be grossed out. That fascination is a part of learning. She offers to show the amputation kit she uses for the demos, should that be of interest. Despite all these thoughts, I decline.