I was about 20 works into the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s (SAIC) Spring Undergraduate Exhibition in Sullivan Galleries when I bumped into a friend, who promptly offered me a map of the show. When I opened it and saw six long columns of names and hundreds of numbers scattered around a layout of the gallery space, I realized that I had barely scratched the show’s surface.

The show, open through most of March, compiled the work of 290 senior BFA students, so it was bound to have something for everyone. And as I walked down the corridors, I found that a map was, oddly, a suitable metaphor for the art I found most compelling. I wouldn’t dare to pronounce an overarching theme for the exhibition, but a common thread in the art that most resonated with me was geography and, consequently, one’s place in the world.

The medium that engaged in this idea the most was fibers, as I soon discovered in “Miigwech to the Land Who Remembers,” by Ash Wolfe (BFA 2019). The piece, hung from the ceiling, was a long, vertical cloth with green and blue patches. These shapes, the wall text explained, formed a composite map of several Ojibwe reservations, including one with which the artist’s family is affiliated. The weaving vaguely formed grasslands, rivers, and lakes, with no intent to be accurate, a representation of the land’s constant fragmentation by different conquering powers. Yet as much as the piece showed fragmentation, its ultimate goal was to reclaim land; the entirely biodegradable work will be buried after the exhibition, so the seeds the artist planted within it can sprout.

I found a similar sentiment in a work by Carolina Vélez Muñiz (BFA 2019), whose art also dealt with indigenous themes. Titled “Ya se nos petatió: entre Los Reyes, Bacalar y Teotihuacán,” it combined two pieces, a woven blanket and a petate, a palm fiber mat traditionally used in Pre-Hispanic Mexican culture to wrap the deceased (the piece’s title alluded to a popular Mexican phrase that colloquially translates as “he/she kicked the bucket”). The blanket, according to the artist’s written instructions, showed an abstraction of a landscape that the viewer was invited to unfold and explore. Bright red and green color patches mixed with gray and brown surfaces, emulating festive decorations in a concrete jungle that could be anywhere between Mexico City and Chicago.

Speaking of concrete jungles, William Ten Eik’s (BFA 2019) piece was hard to miss. Several concrete blocks and electric fans formed a wall around 5 feet tall and 8 feet wide, mostly covered with several fragments of U.S. flags that together assembled an upside-down Star Spangled Banner. On its uncovered side, dozens of smashed toy cars were pasted on the building blocks, creating a miniature vertical junkyard. A commentary on the proposed U.S.-Mexico border wall immediately came to mind when I saw it, so I was quite surprised when I read the name of the piece: “Detroit.” In hindsight, I guess it was about a border town after all.

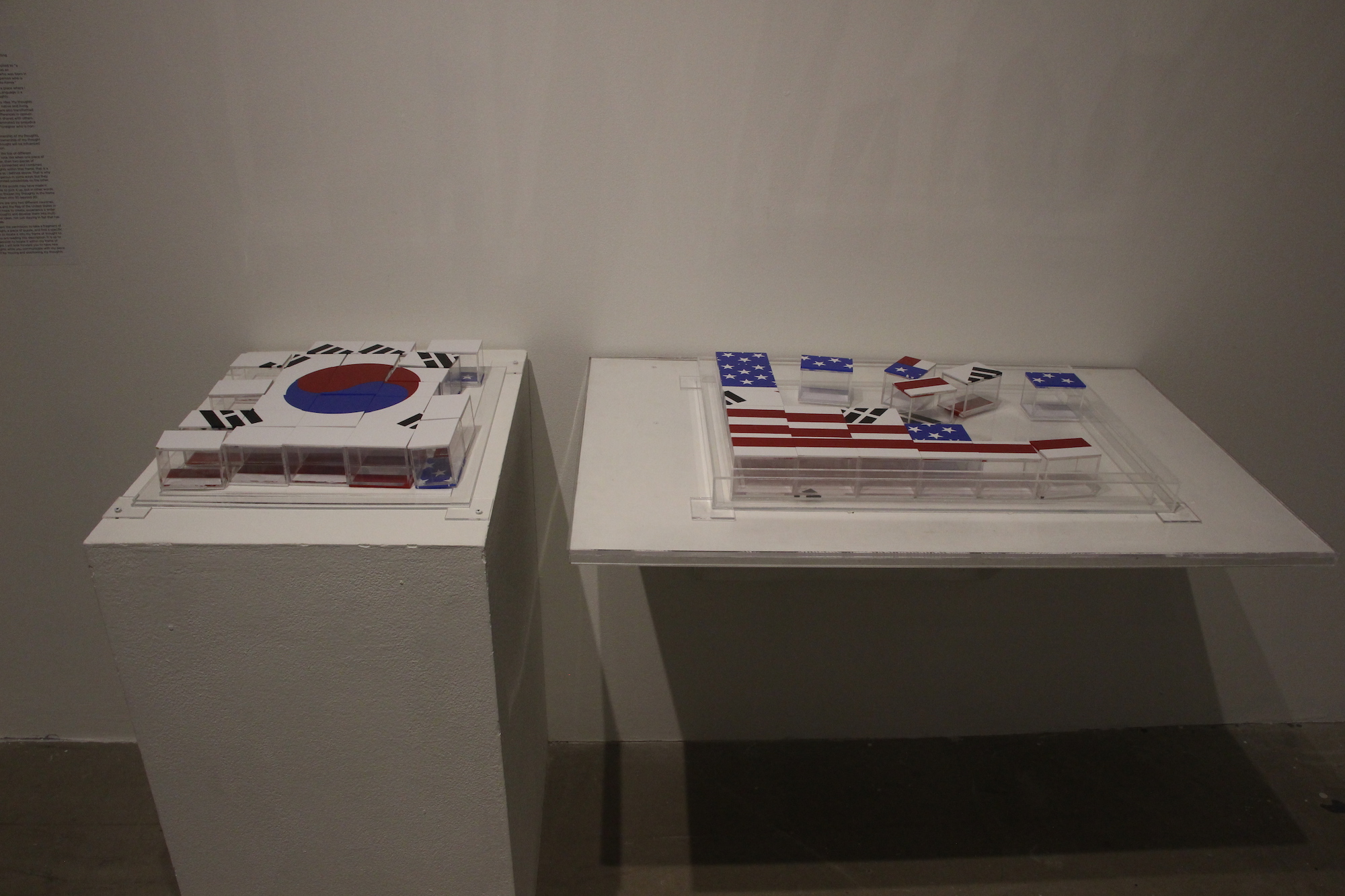

All of the works mentioned so far were in the relatively larger spaces of the galleries, either near the windows that look over State Street or in the wider, outer corridors. But the exhibition also rewarded those who ventured into the smaller rooms in the inner section of the space. In one of these I found another piece that powerfully touched on the theme of place and identity: Seung Ryul Victor Lee’s (BFA 2019) “The Frame of Thought.” The work incorporated two tables, each with a clear plastic frame, on which there were rectangular blocks. Each block showed a section of the American flag on one side and the South Korean flag on its opposite side, and the viewer was encouraged to move the pieces around and flip them. This resulted in one table showing a mostly Korean flag with the occasional white stars on a blue field appearing in the middle, or the Korean diagonal black lines combining with the Stars and Stripes on the other frame. After a prolonged exposure to another country, as the artist stated in the wall text, a person’s own thoughts blur geographical and political lines.

In such a large and diverse exhibition, showcasing work by students with so many different ideas, interests, and origins, it was easy to get lost and feel overwhelmed at the sheer amount of art within the galleries’ walls. But braving the show with a map in hand was gratifying, as I discovered while nearing the end of my visit. I noticed an artwork just a few feet away from the main doors: the photographic triptych, “I was there and I am here,” by Jeonghoon Park (BFA 2019). Printed on rice paper, the black and white pictures — the first two showed snow-covered twigs, the third one a crumpled-up beer can — managed to convey the beauty of a gritty, quotidian Chicago winter scene. The presentation on long, vertical frames suggested a traditional Asian approach, per the wall text. The photographic images then captured these objects in a painterly fashion, consequently encouraging a closer look.

Determining what we look at is simple: it is what is present, wherever we go. The way we look at things, however, is a lot more complicated, and it takes much more than a map to understand.