When Manuel and Patricia Oliver remember their son Joaquín’s last day alive, they each pull a necklace out from inside their shirt. Each necklace carries a transparent container with a small yellow flower taken from the bouquet he gave to his girlfriend for Valentine’s Day.

“Guac,” as the 17-year-old was known by his friends and family, was killed on February 14 of this year during the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. Now his parents travel around the country to keep his voice alive.

“We carry him with us everywhere we go,” Manuel says, clutching his necklace. “He still has so much to say.”

An artist by trade, Manuel has geared his art towards activism after his son’s death. In every city he has visited with his wife since the shooting, they have worked on a new piece for “Walls of Demand,” an ongoing series of 17 murals usually painted in front of live audiences at protests against the National Rifle Association.

The mural and installation the Olivers created for the National Museum of Mexican Art, however, has a different feeling from their previous work. Earlier pieces show an outpouring of rage as Manuel paints the words “We demand a change” in black ink and a roller, then, with a hammer, punches the surface 17 times, one for every Parkland victim. Now, for the Pilsen museum’s Day of the Dead exhibition, open since September 21, the work is a celebration of Joaquín Oliver’s life.

Originally from Venezuela, Manuel and Patricia had never participated in this Mexican tradition before. While not a typical Day of the Dead ofrenda or altar, their piece serves a similar purpose to one. Titled “La Lucha Sigue” (The struggle continues), the offering gathers some of Joaquín’s belongings to remember his most exceptional qualities.

“For this piece, we didn’t want to leave the activism out, but we did want to remember him as the joyful and vocal boy he was,” Patricia says. “If our son were alive, he would be protesting with his classmates. That’s why we do this, so he can still have a voice through us.”

Perhaps the most recognizable part of any altar is the marigold or cempasúchil flower with yellow petals, believed to guide spirits to earth on the Day of the Dead. Though the piece has no marigolds, it has flowers of different colors all over its surface, most of them emanating from a megaphone that Joaquín holds in a black-and-white stenciled photograph.

Its top section in particular concentrates the yellow hue of a row of 17 sunflowers, a tribute to all the Parkland victims and a constant element in every mural of their series.

“Out of respect, we don’t show faces or names of any other victims, but we always remember them with sunflowers,” says Manuel, “it’s the same color of the last flowers our son held.”

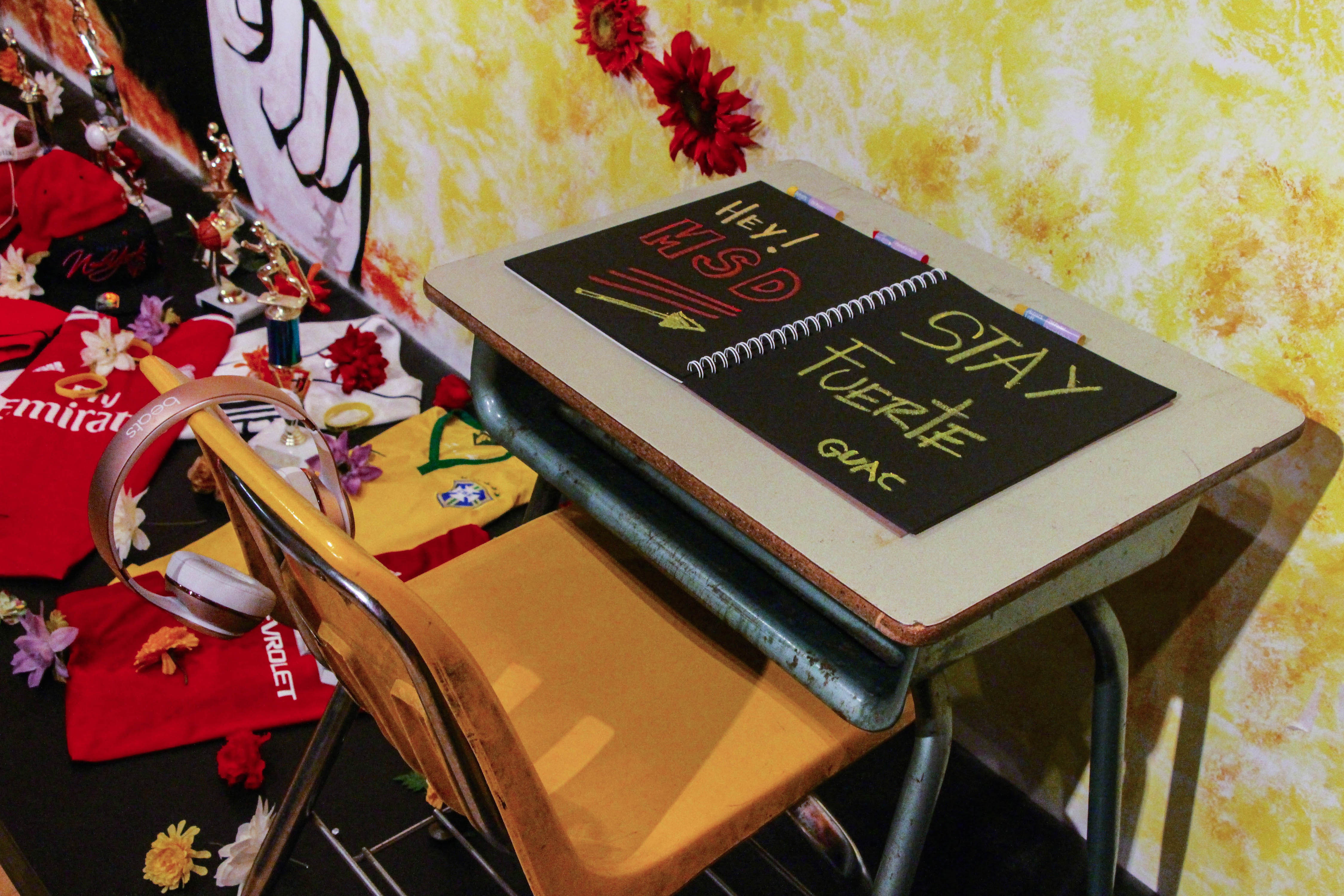

Several of Joaquín’s sports jerseys and baseball caps cover a section of the floor right in front of the mural. Among them rise a few baseball and basketball trophies.

“He was a huge sports fan,” Joaquín’s father remembers. “He celebrated every victory of La Vinotinto [the Venezuelan national football team] and was very proud of his heritage.”

Joaquín not only supported professional teams, Manuel adds. He also went to every sports game he could at Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

“He cheered for everyone, that’s why so many people knew him and loved him,” he states.

On the back of a school chair hangs a Beats headset that was often over Joaquín’s ears or around his neck, Patricia recalls.

“He was a teenager, so he loved rap, he was a big Frank Ocean fan, but I loved that he would listen to all kinds of music,” she says. “He would often listen to The Ramones with his dad, and when he wanted something from me, he would woo me by playing my favorite songs.”

At the far right of the mural is a metallic desk, one of a series of ten sculptures Manuel helped create in the aftermath of the shooting. The figure of a little girl cowers underneath it. Words are etched onto its surface in the same style as messages written by bored teenagers at school. Their content, however, is a list of alarming statistics: “twenty-two kids are shot every day in America;” “Nearly 60% of teens say they are worried about a shooting happening at their school;” “Black children are ten times more likely than white children to be fatally shot by a gun.”

Next to the first desk is another one, Joaquín’s. It has been empty since February, but that, says Patricia, will not stop her son from continuing to cheer for his classmates.

“Joaquín was such an intelligent boy. He was perfectly bilingual and he loved to read and write in both languages,” Patricia remembers.

On the desk is a black notebook with a short message scribbled with crayons: “Hey, MSD, stay fuerte.” Signed, “Guac.”