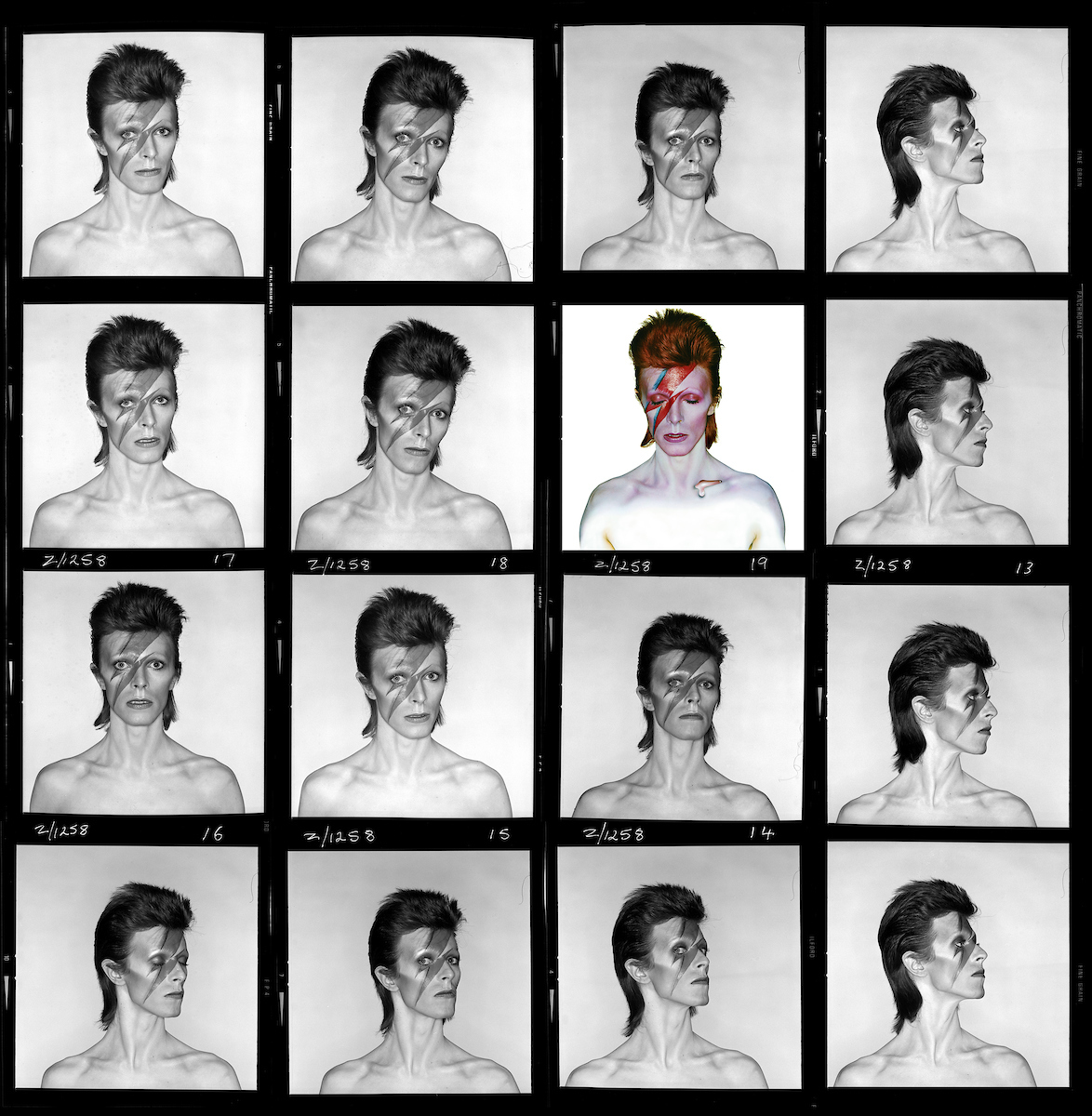

Aladdin Sane contact sheet, 1973. Photo Duffy © Duffy Archive & The David Bowie Archive

There should be no manipulation of the image without permission from the copyright holders.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock the last five years, you’re probably aware of “David Bowie Is,” the traveling retrospective of a man most famous for his chameleon-like approach to music. While the show will give joyous heart palpitations to any Bowie diehard, its pleasures are greater than glitter and fan-service. The name implies something biographical, like the exhibition, will offer insight as concrete as the things on display. Instead, nearly 500 objects (about 100 of which are unique to this installation) are thoughtfully curated to give an impression of an elusive man whose output was so diverse, he’s impossible to define.

Much like Bowie, the exhibition was born in London. It debuted in 2013, at the Victoria and Albert Museum with an uncertain future because it wasn’t your typical art show. Even when it crossed the pond to MCA Chicago a few months later, critics wondered why a rock star was being given an entire floor in a contemporary art museum. Perhaps to no Bowie fan’s surprise, the show performed much like the man: unpredictably but magnificently. Amidst record-breaking sales, the Brooklyn Museum gives it its final send-off, putting his drawings, jumpsuits, and music videos to rest in the same city where Bowie lived out his final days.

Tickets include temporary use of Sennheiser headphones — clunky little earmuffs with a retro vibe that act as a time machine as much in their aesthetic as the audio they deliver. Approaching different parts of the show activates various sound clips, which controls your pace through the experience. Linger too long in any one section and you might hear a repeat of Bowie ranting about being persecuted for having long hair or a second helping of his “Saturday Night Live rendition” of “Man Who Sold the World.” In some ways, these loops feel luxurious — like being stuck in the groove of a wonderful record or a time echo.

Wireless devices interfere with the audio, so cell phones must be turned off before entering “David Bowie Is.” In the internet age, it’s rare to have an uninterrupted, collective experience — especially one that can’t be broadcast on social media. Similar to taking in a concert in 1974, viewers have to live in the now, cocooned in something that stimulates multiple senses but for a fixed amount of time. I could liken it to a movie, but that ignores how visitors’ bodies move through the show, that people are dancing in a museum and everyone understand why.

David Bowie is, March 2, 2018 through July 15, 2018, installation view. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

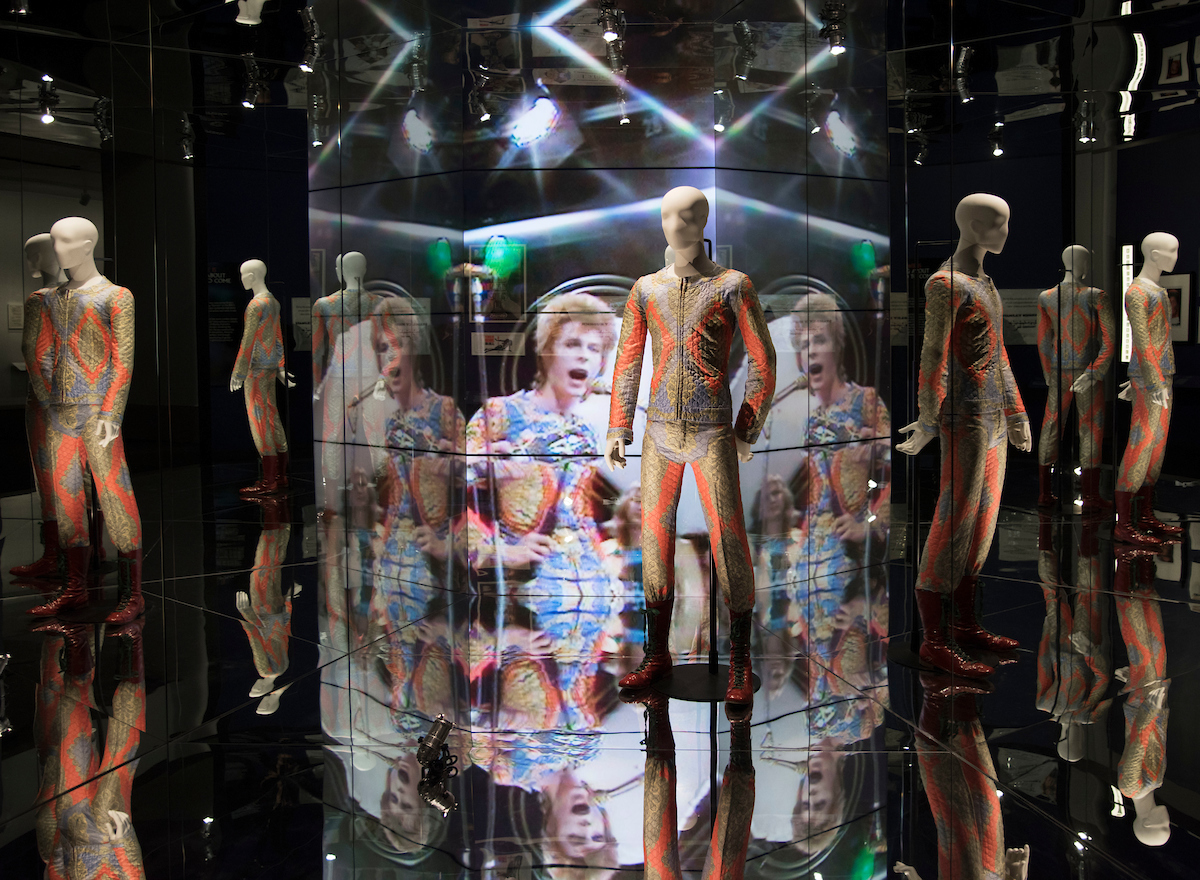

Coupled with stunning visuals — everything from set designs to fan art to original costumes — the audio makes “David Bowie Is” an immersive, multimedia experience similar to the work Bowie made. Most people pigeonhole Bowie as a musician, but he was the essence of an interdisciplinary artist. From organizing a performance art festival to collaborating with Nam June Paik before MTV, the medium Bowie most often played with wasn’t music so much as time. He just did it in a way where he was trying to reach a wide audience.

The show opens with relics of Bowie’s upbringing in Brixton, a London neighborhood and post-war nexus of public housing scarred as much by economic inequality as WWII bombs. Though Bowie had an early interest in music, he took to painting, too, and dropped out of school at 16 to work in advertising. By his late teens, he was involved in the London performance art scene, studying dance, miming, and avant-garde theater under teachers such as Lindsay Kemp. Since childhood, Bowie couldn’t resign himself to being any one kind of creative, but his upbringing imparted a sense of populist urgency.

By the mid-60s, Bowie’s proximity to the London avant-garde had left him increasingly dissatisfied with underground culture — something “David Bowie Is” hints at but I think is essential to understanding his output. In interviews, he described the underground as a middle-class institution that wasn’t really helping the people most in need. Populism was important to The Man Who Fell to Earth because, though he never quite saw himself as of this world, he always wanted to communicate with many parts of it. That’s why he gravitated towards film and music, maintaining a diverse visual practice but never comfortably settling into life as a capital “a” artist.

After meditating on Bowie’s earliest days, the first leg of the exhibition ends with the release of “Space Oddity.” That album was his first big hit but hardly what catapulted him into fame. Turn a corner, and you’re right in the church of Bowie, worshipping at the altar of Ziggy Stardust, Bowie’s best-known persona and the character that launched him into international superstardom. From there, the show stops being chronological and starts being a winding, meditative journey, showing Bowie as a translator of influences, ideas, and approaches. For instance, in goes Hugo Ball’s Dada performances and Tristan Tzara’s “The Gas Heart” play; outcomes Bowie’s “Saturday Night Live” tuxedo — which was then filtered through his SNL backup performer Klaus Nomi to become Nomi’s signature look. Bowie was masterful at being influenced and influencing.

David Bowie is, March 2, 2018 through July 15, 2018, installation view. (Photo: Jonathan Dorado, Brooklyn Museum)

My only complaint about the Brooklyn Museum’s show is how most of Bowie’s outfits are displayed. At the MCA, his garments were so close you could almost see him breathing in them. As an idea, Bowie is superhuman, but seeing his clothes right in front of you — that crocheted one-legged jumpsuit from the Ziggy Stardust/Aladdin Sane tours or the ice blue Freddie Buretti suit from the “Life on Mars?” video — you felt like you could wrap your arms around all 26 inches of his waist. How extraordinarily real he seemed.

In contrast, the Brooklyn Museum puts many of his clothes above eye level. Stare into the padded crotch of a white silk romper. Struggle to see the details of a glittering turquoise lightning bolt jumpsuit being exhibited for the first time since he wore it exactly once in 1973. Here, David Bowie is larger than life. The part where he feels most human is some never-before-seen footage of him trying way too hard (and failing) to impress his hero, Andy Warhol. It’s a quiet snippet, easy to overlook — but well worth hunting for.

At the show’s climax, there is a large room with rows of benches where visitors cast off their headphones to take in both rare and never-before-seen performance excerpts projected onto three walls. Sometimes, each wall plays something different, but in one rapturous moment, two walls show the same clip from Bowie’s final night of the Ziggy Stardust tour. The other shows a closeup of his fans riled in wonder, awe, ecstasy. Their tears are your tears. Will there ever be a more convincing facsimile of a nearly 50-year-old concert?

Since Bowie’s death in 2016, the show has been adapted to include process notes and ephemera from “Blackstar,” his final album. One of the successes of “David Bowie Is,” is that it resists memorializing him. On your way out, there’s a chart— “The Periodic Table of David Bowie” by Paul Robertson — that loosely shows, not only who some of Bowie’s biggest influences were, but who Bowie influenced. If David Bowie is any one thing, he’s timeless.

“David Bowie is” is on view at the Brooklyn Museum, 200 Eastern Pkwy, Brooklyn, NY, through July 15.