“It feels like election night,” a friend joked as the nominees were being read for Best Picture at last night’s Academy Awards ceremony. Though we all laughed at the exaggeration, there was much at stake. The enduring image of American popular media during the first year of a troubling administration; the icon of our culture at a truly difficult time; the evidence of our resistance to an oppressive political regime built on hatred, lies, and bigotry — with that and more on the line, one might forgive my friend her anxiety.

As scenes from a long list of beautiful and powerful films were shown, it was hard to shake the feeling that, in the end, it would come down to two: Will it be “La La Land?” Or will it be “Moonlight?”

It was a prizefight. Hyped (over-hyped, some might say) for months by an ever-growing number of angry thinkpieces (I wrote one), it was easy to see this award as, well, black or white. “La La Land” was being praised as an escapist homage to the joys and struggles of classic Hollywood. “Moonlight” was being held up as Hollywood’s first truly intersectional film, telling a story that needed to be told and not a second too soon.

What happened was itself pure drama. I confess that there was something poetic and fitting about watching a predominantly white cast and crew physically make way for more deserving people of color. It was, in its way, the antidote to “La La Land”’s troubling but largely-accurate worldview. Sometimes the right people win.

We were told to see “La La Land” as playful fantasy, but its central problem was that it wasn’t fantasy. It was reality being sold as fantasy, and some of us weren’t buying. What many saw as a nostalgic tribute to a famous city, we saw as something more insidious – a reinforcement of the kind of mediocrity you can peddle in that city if you’re just the right kind of pretty and pink.

Part of the problem that “La La Land” encountered was the difficult-but-promising truth that it has become increasingly hard to sell a white man as “everyman” in a country where people of color are the fastest-growing population. And it’s hard to sell Ryan Gosling as a “dreamer” when our real dreamers today look a lot less like John Lennon and a lot more like John Legend.

When you take the reality of white dominance and push it as romantic fantasy, you’re bound to get pushed back, and this is where “La La Land” took its fatal heel-step. It was a backward-looking film for a forward-looking time.

But where “La La Land” strove to create fantasy out of reality, “Moonlight” strove to create reality out of fantasy.

In many ways the more “realistic” film, “Moonlight” actually creates a beautiful but mythical world where the seeds of love can grow anywhere, anyhow. It’s a world that doesn’t exist yet. Yet. It’s a world that needs to be dreamt before it can be made. “Moonlight” had the audacity to dream it.

When our favorite film loses, we kick and fuss and say that the Oscars are dumb anyway and none of it matters, but here’s the thing: It does matter. It matters for the filmmakers, certainly, who get mainstream recognition, exposure, and validation, and whose careers are very much on the line; but it matters, mostly, for everyone at home who gets to see just what kinds of films and just what kinds of people get rewarded. For a moment last night, the story – the world – looked the same. It looked like “La La Land.” But then, suddenly, it didn’t.

It looked like a dream.

It looked like fantasy.

It looked like “Moonlight.”

Something important happened last night, and it happened at a dumb awards show. We were told, as we too-infrequently are, that the nostalgic narrative of white success is not the only narrative that gets rewarded. That it is not the only narrative of value. That it is not the only narrative.

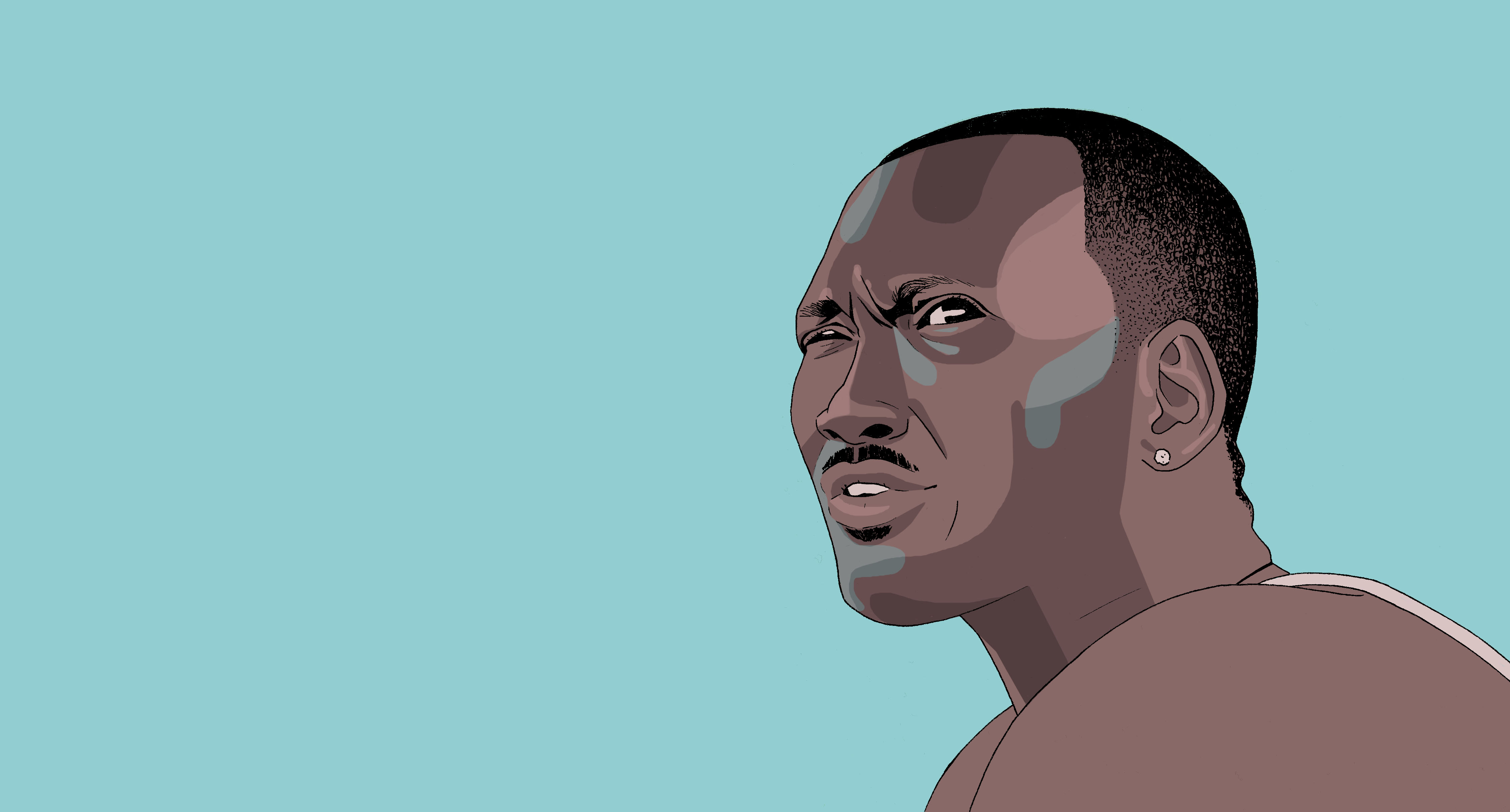

Moonlight dreamt the world we need and, last night, it took a massive step toward making it. Mahershala Ali became not only the first Muslim to win Best Actor in a Supporting Role, but the first Muslim to win an Oscar at all. Moonlight became the first all-black cast to win Best Picture, as well as the first queer-centered film to win Best Picture. Barry Jenkins became the first black man to be nominated for Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay in the same year. Joi McMillon became the first black woman to be nominated for achievement in Film Editing.

Just two days after the Huffington Post published an article about how on-screen representation influences psychology, seeing a stage full of people of color accepting Hollywood’s highest honor is not only powerful, it is vitally important.

The right film won last night. “La La Land” and “Moonlight” were both beautifully shot, commandingly acted, emotionally moving films; but in a dark time, we need to look forward, not backward. We need to turn fantasy into reality, not the other way around.