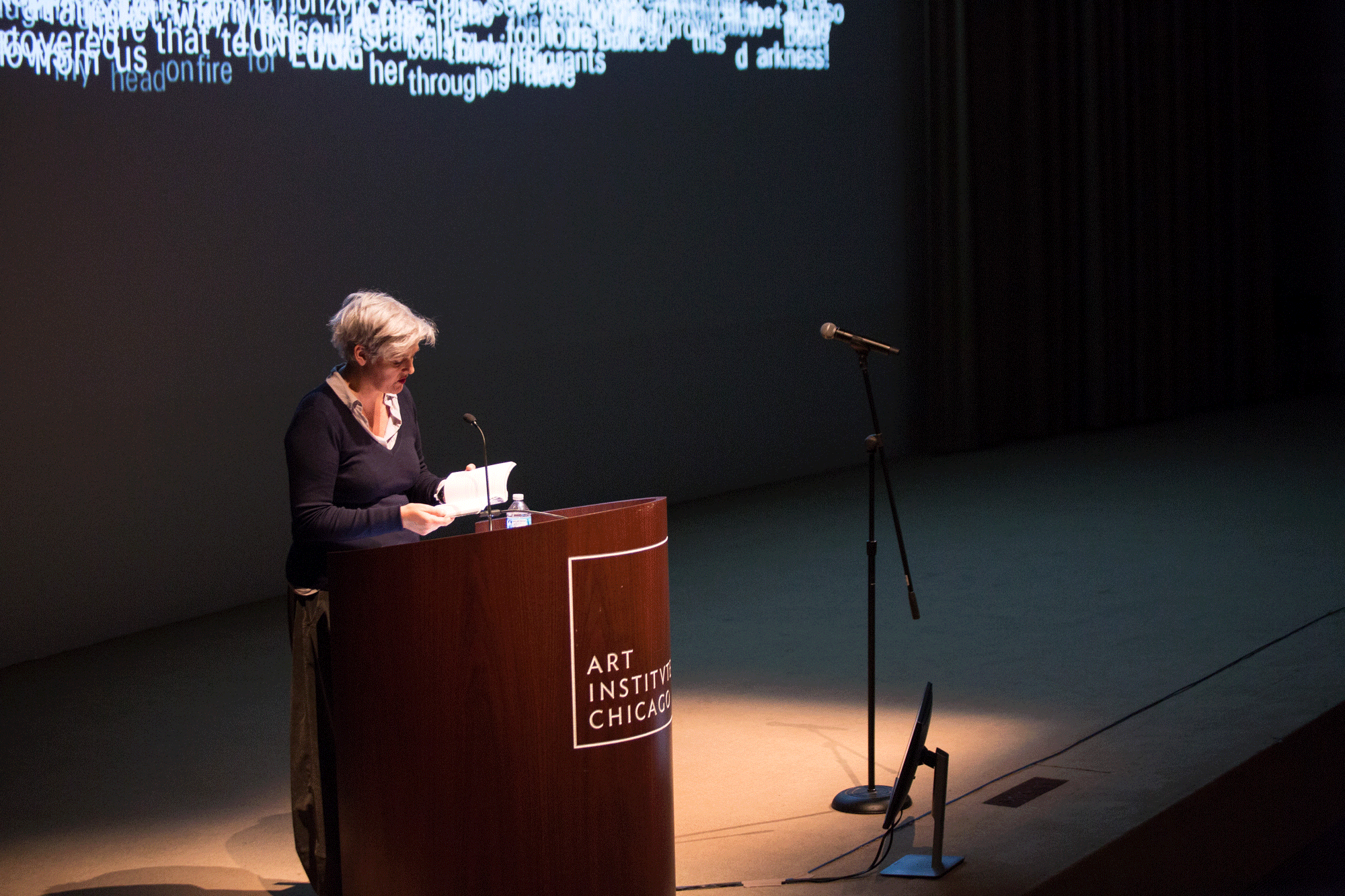

Photograph by Farah Alhaidar. © 2016 School of the Art Institute of Chicago; All Rights Reserved.

Artists Caroline Woolard and Caroline Bergvall both visited the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) on the Tuesday evening the week after the 2016 U.S. presidential election. In the space of six days, emotions campus-wide cycled from shock to grief to rage to fear to hopelessness to broken-heartedness. On November 15, the moods in both the Rubloff Auditorium and the Nieman Center were palpably vulnerable.

“This how it feels to be here right now,” Bergvall prefaced before reciting her work, which culminated in breathing out a lengthy string of “oh-my-oh-my”s in one long, drawn-out exhale. Rising to crescendo and falling to a whisper, the artist modulated volume and speed as she sculpted her breath through her body and into the microphone, words dissolving into a thread of unbroken sound.

“How does one keep one’s body as one’s own?” she asked.

In her practice, Bergvall plays with a variety of formal strategies, layering sounds and languages, to call the audience’s attention to the word as a placeholder for meaning. If I were to write the above paragraph in three languages, interpolating, say, English, Spanish, and French as on a shampoo bottle’s label, perhaps you would pause long enough to see the words, even for a split second, as abstract symbols and not immediate, unalienable truths. There’s a synaptic space in between word and meaning.

Bergvall probes questions of language, liberation, and the body through projects like “Drift” (2013 to 2015). In the piece, Bergvall, through layered words and languages, juxtaposes the ancient literary journeys of maritime poetry and mythos with the current refugee crisis, giving voice to the not-loud-enough stories of refugees fleeing political oppression by sea.

Building off Bergvall’s question about keeping one’s body as one’s own, comes another artist’s question: How can artists problematize extractive systems and work towards societal healing through solidarity economies?

Enter Caroline Woolard; same Tuesday evening, different SAIC stage.

“I expected to be in a lecture hall. This is already different. This is interesting,” Woolard said of the corner of the Nieman Center, where a few dozen audience members gathered.

Most of the time, Woolard pointed out, when artists gather in academic spaces, “we’re not practicing the practices that make up the work.” She continued to explain that most of the time, we’re not making art together. Rather, we’re sitting in chairs looking at images — visual illusions of purported projects — and talking about these illusions using circumscribed language.

“Be wary of the lecture, be wary of the lecturer,” Woolard warned, with a smile.

To model a radical transparency, Woolard engaged the content of her artwork in the form of the talk itself. (Content, in this case, is the overarching theme of solidarity art economies; for example, the barter economies of Woolard’s collaborative project “BFAMFAPHD.”) The talk became a consensus-based meeting, with intentional framing at the outset, including naming of identity-based positions in the room. Woolard discussed race and class privilege and a commitment to a constant process of unpacking, citing anti-bias resources like “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack” by Peggy McIntosh.

“I like to make agendas; I participate in many groups,” Woolard said. “I’m going to time myself.”

She projected an itemized list on the screen, charting the scope and duration of the participants’ time together. Woolard then held a vote: How would each audience member like to prioritize the content of the presentation? Three choices were listed: Technique, Economics, Feelings; majority wins.

With candor and revealed vulnerability, both Carolines stood firm in their art practices. They demonstrated what it can look like to witness artists standing up despite a week when the very ground underfoot feels uncertain.

“Being lost is a way of inhabiting space by registering what is not familiar,” Bergvall said. Bergvall’s message was a plea for artists to continue to oscillate inside the unmapped trajectory. She hopes creators will commit to vigilant attention and presence in the vibrations and in momentary landing places; this lostness is a site and a starting place.

Both Woolard and Bergvall posed questions and structured frameworks towards societal healing through new systems of interaction — be they lingual or economic. They were two distinct role models of active artistic courage during a dark week.

The presentations both modeled ways of being an artist in the world, starting with the room we find ourselves in right now. The Carolines are walking the walk.