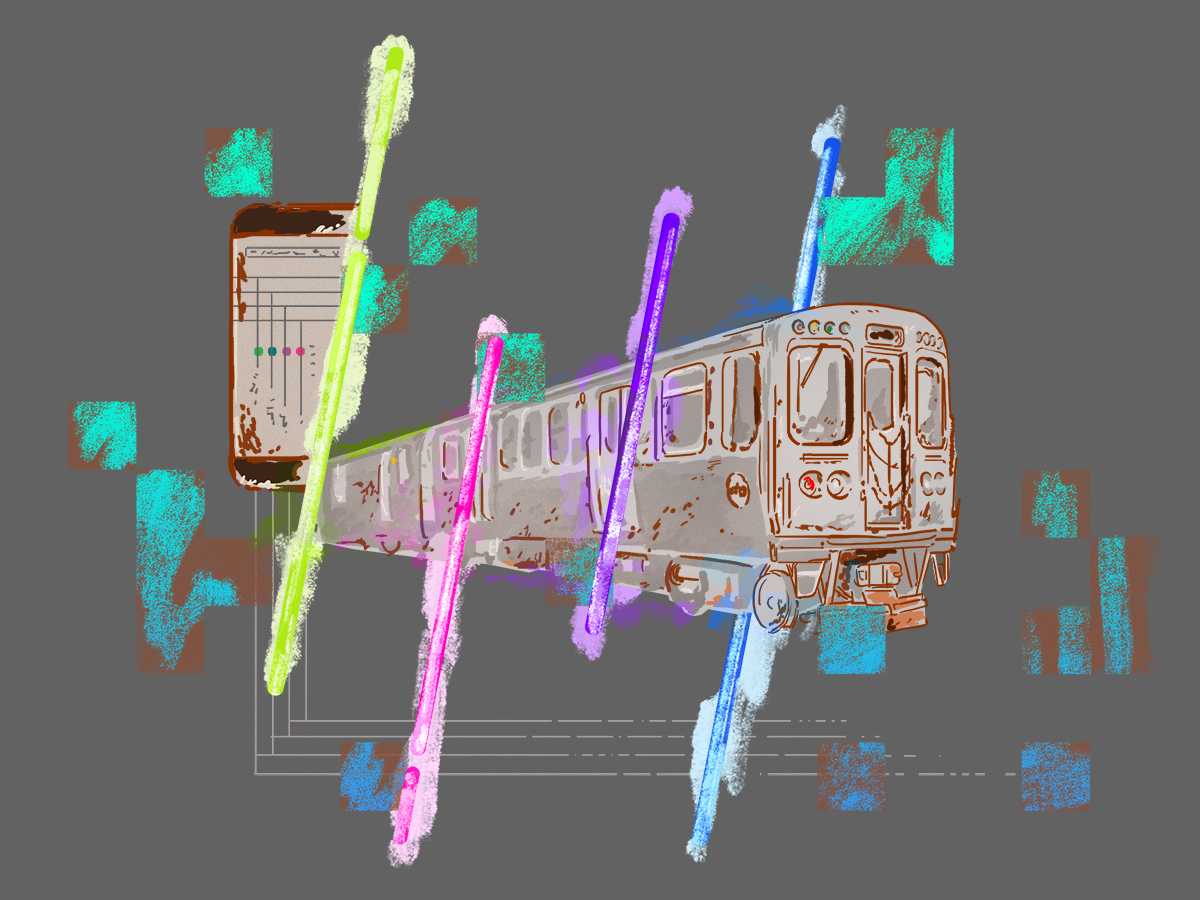

The 21st century offers humans the ability to be present in two realms at once: the physical and the digital. The Wabash Lights, a new public art installation set on the underside of the CTA tracks on Wabash Avenue, aims to bring those spaces closer together.

Creators Jack Newell and Seth Unger started the project over a year ago. Unger, a designer, and Newell, a filmmaker, both hail from Chicago. When discussing the project, a major point of inspiration was to make an installation that was part of Chicago’s identity.

“When we were conceptualizing this project, [we asked], ‘what are the iconic parts of Chicago that celebrate this idea of pride in the city?’ The thing we kept landing on is the elevated L tracks; we’re not the only city in the world who has them, but for some reason they are iconic to Chicago,” Unger told F.

Walking across Wabash between Monroe and Adams, you can look up at the tracks and see the glow of four tube lights three feet long. These lights are the “beta test” for the larger installation.

“What we funded with the Kickstarter was essentially a ‘proof of concept,’” said Newell, who was programming lights on Wabash just last week. “What we’re testing now is boring but important stuff. Like, how does the vibration of the L affect the lights? How does weather? What programming plays best?”

Materials and labor are the biggest allocations of the Wabash Lights project’s budget resources. Large-scale public art installations accrue costs in everything from city road closures to continually testing tech durability.

“That’s kinda the whole point of the beta. The Lights are LED lights in plastic diffuser tube casings that are fairly robust,” Newell said. “But sections of lights have gone out, so we had to send them to Phillips and find out what happened with them.”

“We know going forward that a part of the project will be maintenance. The beta is giving us an idea of what that [maintenance] is going to look like down the road,” added Unger.

The Wabash Lights are an LED installation similar to the Bay Lights in San Francisco. Both projects merge art and infrastructure in a way that complicates the difference between the two.

Newell and Unger come at the Wabash Lights from an artistic perspective, but the more they speak with collaborators about the scope of the project, the more the art blends with other facets of human living such as design, architecture, infrastructure, and public engagement.

“Art and technology have always been intertwined. Science too. We’re doing things that the technology, right now, wasn’t built for,” said Newell. “We’re pushing it in ways it hasn’t been pushed before. And that’s good for technology; that’s good for art.”

“A lot of times, I think one of the reasons this project resonates with people is that we’re taking something very simple and making it into art. There’s nothing special about these lights. We’re just taking things that are readily available and using them in new combinations,” he added.

Unger said this simplicity is the key to both the physical and digital design of the Wabash Lights.

“Sometimes the simplest solution is the best and the most beautiful. I think the number one thing this test was about was turning the lights on for the first time and being like: ‘Is this impactful? Does this look like it did in our imaginations?’”

“The answer was ‘yes,’” added Newell.

What remains to be explored is how digital engagement accesses and manipulates art the public sees every day.

A digital app accompanies the installation, providing a tool for the public to make the physical installation their own.

“The app is where people can create, upload, and share with each other. The lights are their canvas,” said Unger.

The full LED installation would make space along the Lights for three modes of expression through the app. First, there would be space for real-time public programming where people can stand under the lights and manipulate them. Second, people would be able to schedule light displays for certain times. Finally, there would be a space for curated shows.

“The curated displays might involve bringing in artists, whether they be already established or students, to curate a show. They could think of [the installation] as an extra gallery space,” said Newell.

“Every time I’m down on Wabash messing with the lights, a number of people come up and talk to me. The thing that’s crazy about it is, they’re not shy. The art thing lowers barriers,” he added.

“This is the first permanent artistic thing that we’ve planted anywhere in the world. And hopefully not the last,” said Unger.

“Hopefully, not the last,” Newell agreed.

Keep up with the Wabash Lights project by visiting their website here.