Seeking respite from the blistering heat, demonstrators stand or sit under canopy tents and other make-shift shelters at the corner of Fillmore and Homan. They have been staked out here since July 22, enduring rising temperatures and turbulent storms. Across the street from the controversial Homan Square police facility (a proven black site), they are protesting not only the misconduct at the facility, but the proposed Blues Lives Matter ordinance before the Chicago City Council.

The ordinance sponsored by Alderman Edward Burke, who represents the 14th district, comes in the wake of shootings against police officers in Dallas and Baton Rouge. Burke proposed a bill that would make any assault against a police officer, firefighter, or emergency medical crew a hate crime. Critics say the bill will distract from and possibly silence protests against police misconduct. Any assault (including threats and physical altercations) against an officer would become a federal felony resulting in up to six months in prison. The fine for offenses against officers would be raised from $500 to $2500 as well. A similar bill already passed in Los Angeles on Monday.

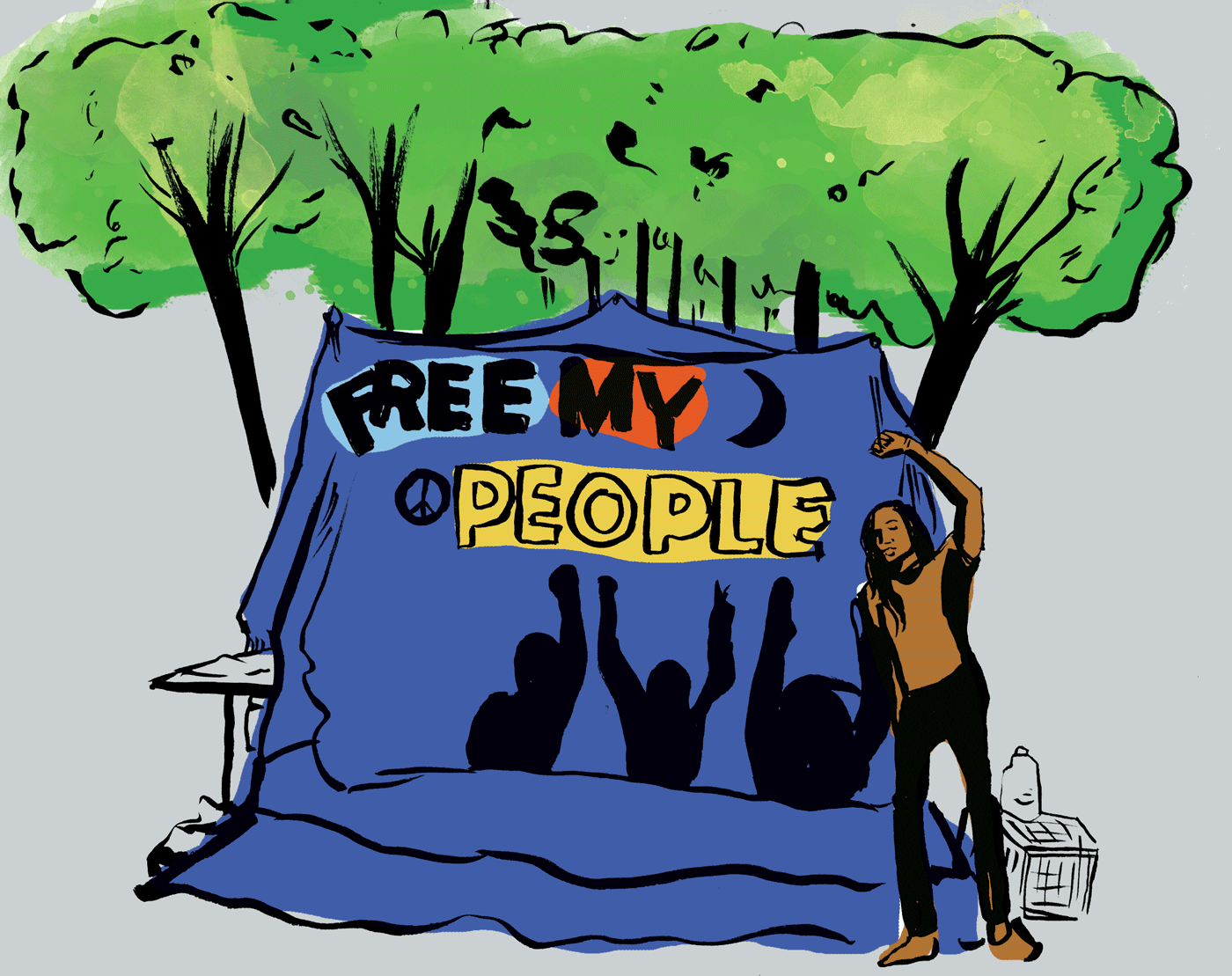

Local community members and activists from across Chicago — together forming the Let Us Breathe Collective — gathered in the empty lot outside Chicago’s Homan Square. They have christened the space “Freedom Square.”

“It’s going great; it’s beautiful,” said Bella Bahhs, the co-director of the Let Us Breathe Collective, in a interview on July 27 at the demonstration. “This is day six of our occupation, and we have engaged hundreds of members of this community. We have fed hundreds of people, and it’s necessary – it’s being proven necessary every single day. There have been kids out here with us since day one, and they are still here, showing that they have nothing else to do. We are providing resources for the community and the children of the community.”

“Freedom Square” grew out of a protest march the week of July 17 in response to the acquittal of police officer Dante Servin, who fatally shot Rekia Boyd in 2012. Several dozen marched from Servin’s house in Douglas Park to the corner of Fillmore and Homan, where the protesters chained themselves together and blocked the intersection for several hours. Police arrested 10 of the protesters on site.

Once the march and blockade finished, protesters gathered at the empty lot at Fillmore and Homan to discuss their next move. At first unprepared for a longterm sit-in, members of the newly formed Let Us Breathe Collective and Black Youth Project 100 returned on July 22 with tents, coolers, and a grill. Acting as a sort of pop-up community center, the demonstrators passed out bottles of water and food to passersby and have created a free-store with hygiene supplies and other items. Sleeping in their cars or in sleeping bags, the demonstrators have now occupied the lot for 12 days.

The occupiers of Freedom Square were quick to point out the overarching political goals of the demonstration.

“One of our immediate goals is to stop the Blue Lives Matter ordinance, which would make protesting police violence a federal felony – a hate crime,” said Bahhs.

Burke, however, argued last month that the ordinance was a necessary protection for the police officers of Chicago.

“Each day police officers and firefighters put their lives on the line to ensure our well-being and security. It is the goal of this ordinance to give prosecutors and judges every tool to punish those who interfere with, or threaten or physically assault, our public safety personnel,” said Burke in a statement reported by the Chicago Tribune.

Repeated attempts by F to reach the alderman’s press secretary for this article were unsuccessful.

Burke’s position is congruent with a growing number of Americans who view the police as a class of people in need of protection, especially in light of recent events. But are these so-called “Blue Lives Matter” bills really necessary for the protection of law enforcement?

“It’s a war on cops,” said William Johnson, the executive director of the National Association of Police Organizations, in an interview with Fox News on July 8. Blaming President Obama for the Dallas shootings and an “increase in violence” against police officers, Johnson continued to criticize the Black Lives Matter movement for vilifying police officers.

However, statistics do not support an increase in violence against cops. In fact, the FBI released a report in May detailing the decrease in felonious deaths of police officers in 2015, showing a decline of 20 percent from the previous year.

Seth Stoughton, a law professor at the University of Southern Carolina, discussed the perception in the American public that law enforcement are under new imminent threat with the BBC.

“There’s a widespread perception in the American public, and particularly within law enforcement, that officers are more threatened, more endangered, more often assaulted, and more often killed than they have been historically. But factually, looking at the numbers, it’s not accurate,” said Stoughton.

The story does not end with the “Blue Lives Matter” bill. Protesters are also at Freedom Square to bring to light the ongoing misconduct at the police facility where they’re stationed — a site the Guardian reported last year was a black site where law enforcement officials seek to lose arrestees, mostly African American, in the system.

The Homan Square facility does not maintain public booking records, concealing the whereabouts of detainees from lawyers and family members checking their closest police stations for information. Thanks to a transparency lawsuit by the Guardian in 2015, we know now that of Homan Square’s released 7,000 detainees over the past decade, 82 percent were black; 75 percent of the arrests were for drug-related charges for minor possessions or dealings of marijuana, heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamines.

The Chicago Police Department failed to release any information on those held at Homan Square who had not been formally charged with a crime, but the Guardian found seven such cases, including the case of Charles Jones, who they profiled.

Jones, who was detained at Homan Square on March 17, 2015, gave an interview to the Guardian detailing his stay at the facility. Handcuffed to “a ring around the wall,” he said he was held for six to eight hours without access to a lawyer or phone while police tried to extract information from him. “The only reason you’re brought to Homan and Fillmore is to extract information,” said Jones.

“Freedom Square” is near the Nichols Tower, where the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) recently received a National Endowment for the Arts grant of $75,000 to support new programs with the Homan Square Arts Initiative. The site now offers free community art courses, an artist in residence program, and civic-minded design projects.

When asked about possible ways SAIC could become involved in the demonstration, Bahhs and others mentioned the need for art supplies for the children of the neighborhood to use. Another way to help, she added, was simply to distribute the message of the peaceful protests to as many people as possible.

“They’ve been disappearing black folk [at Homan Square] for at least a decade. We want to make blackness visible on this side of the street and point out the problem and provide a solution. And that solution is ‘Freedom Square,’” said Bahhs.