On October 16, Jodi, the Netherlands-based art collective comprised of Dutch artist Joan Heemskerk and Belgian artist Dirk Paesmans, spoke and screened their work at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Introduced by SAIC Film, Video, New Media and Animation Chair and glitch artist Jon Cates, Jodi exhibited a selection of their trailblazing explorations in net.art, artware, net games, and glitch from the 1990s to their recent explorations.

Guided by a mix between an anarchic and pioneer spirit, Jodi constantly transgress the lines of user-friendly graphics, introducing a very human scrawl into what aims to be the orderly realm of machines.

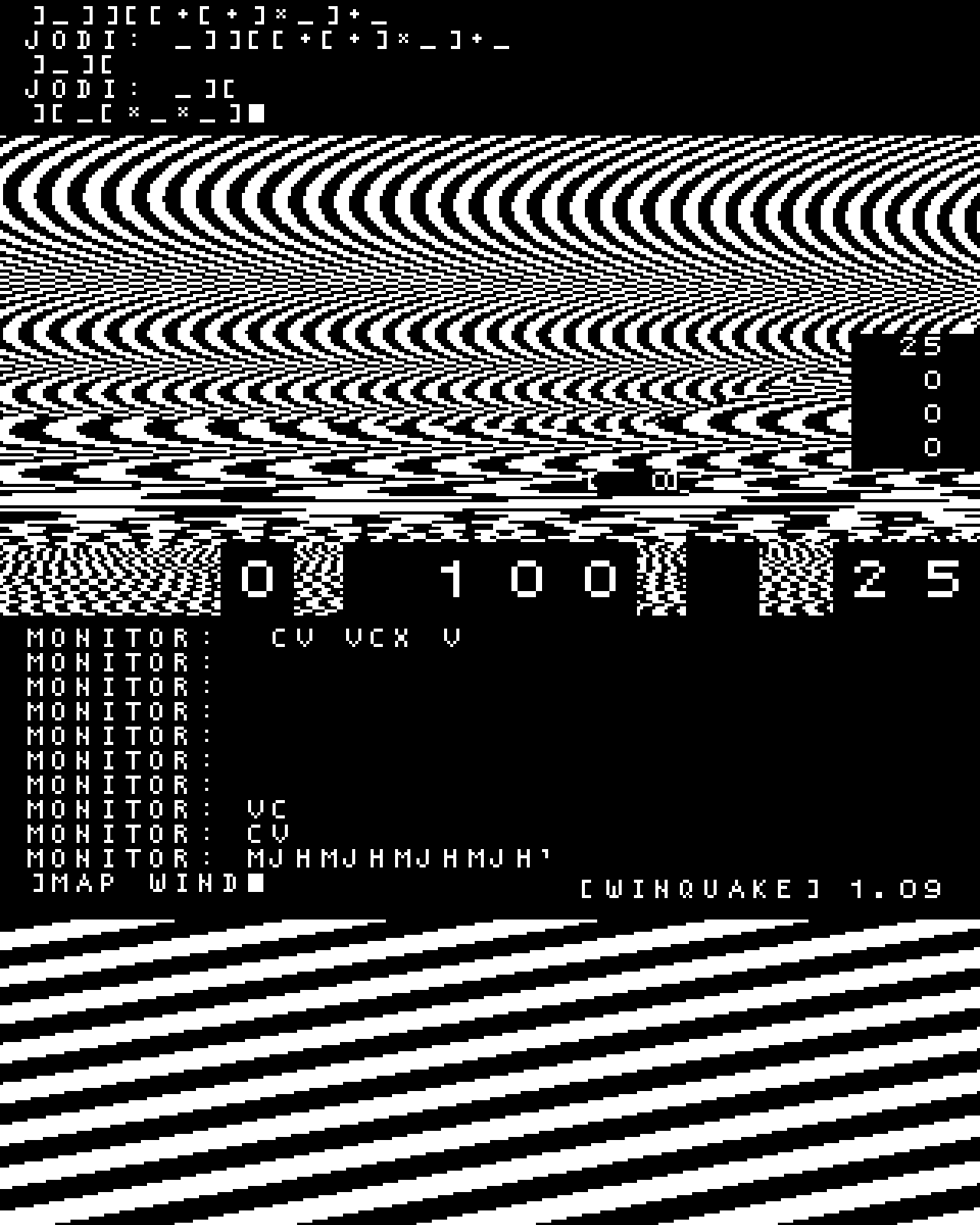

The lecture began with the screening of “Untitled Game,” Jodi’s modification of the 1996 video game “Quake.” Against a backdrop of crunching hisses and thuds, black and white lines blur and flutter, the patterns forming a dense, abstract field.

Another modification, “Arena,” displays a white screen on which programmed phrases like “YOU FOUND A SECRET AREA!” and “YOU GOT THE NAILS!” flash at random while a life count rapidly drops at the screen’s bottom. The piece ends with the disclosure that the character has been “EVISCERATED BY A FIEND.”

Jodi then presented an app they created, “ZYX APP,” in which “the user is the player,” said Paesmans. In a video demonstrating its use, a young man holding his phone spins in the midst of perplexed onlookers in a museum gallery. Next, he bobs back and forth in the street, the game clicking each time he hits a censor’s mark. A green box flashes when the player successfully completes challenges like turning to the right sixty times, or searching for North and standing still for sixty seconds.

Paesmans said of their app, “The player’s reaction is outside of the screen and the screen is like the command — the score, almost.”

Jodi then presented a video of themselves drilling into the screen of an iPad, the screen cracking and flaring with leaking green light. Asked whether this was an aesthetic experiment or an attack on technology in the tradition of Nam June Paik, Paesmans explained, “I’m a student of Nam June Paik’s, I was in class with him. I like destruction in art. I was inspired by groups that were doing that. At some point I found these groups of kids destroying their Game Boys, smashing their laptops. We collect work of this creative destroying of technology.”

Heemskerk and Paesman then presented a work in which they wreak havoc on a computer desktop. Paesman said that the duo were interested in “improvising on the desktop, the desktop as the main space to play with.” As error notifications bleep and folders multiply, the piece becomes a comical symphony of error, choreographed to provoke maximum irritation.

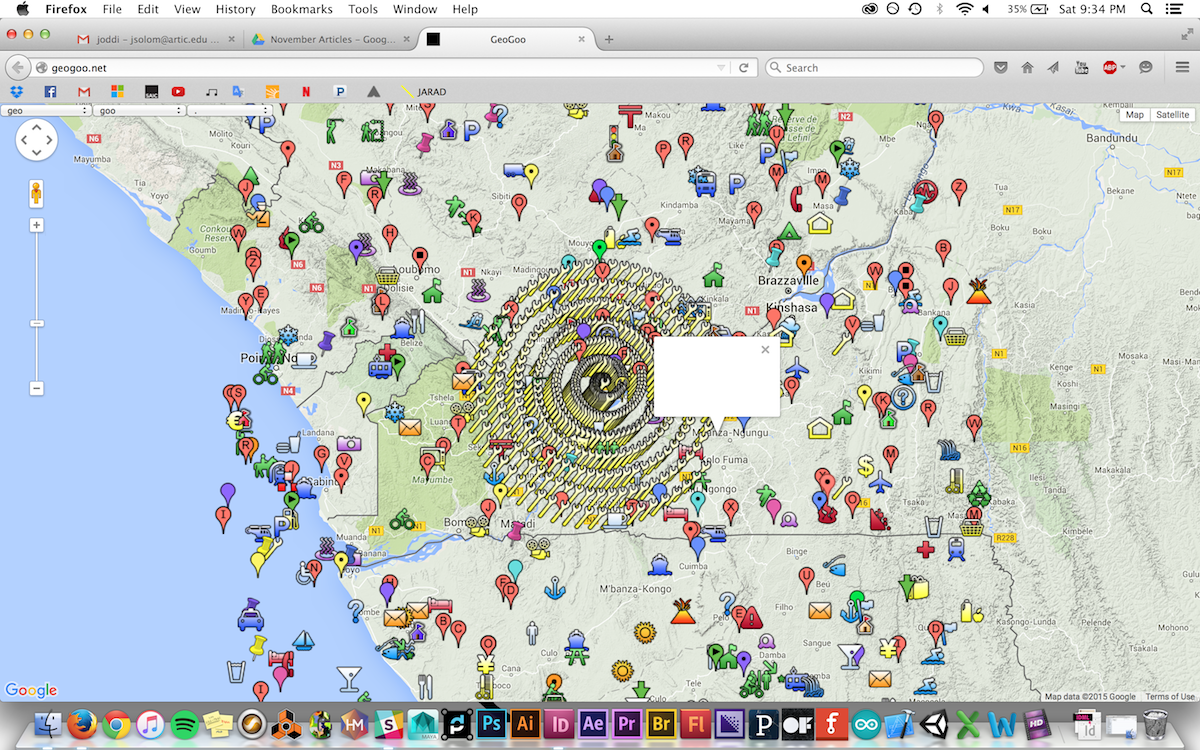

Next, Jodi exhibited “GEO GOO” (2008), in which the icons of Google Earth spiral swiftly across Google’s maps to form abstract, symmetrical designs. Euro signs, house symbols, and a walking man’s form light up over the vague representation of earth, the forms’ rapid motion perhaps implying our metaphysical engagement with the Internet. The piece builds a sense of unbounded movement as a swarm of signifiers voyage across oceans and planes.

Jodi plays with language in much of their work, often finding significance in the browser bar. Their elastic view of language corresponds to the transformation of text throughout the digital era. In one work, the two posted banners around Beijing emblazoned with nonsensical URLs (bizbizbizbizbiz.biz; IlikethisIdislikethis.com.) Paesmans referred to the project as “URL graffiti.”

The two also poke fun at technical language in a piece in which the voice of video game character Duke Nukem reads the options of text edit, booming, “TEXT EDIT. ABOUT TEXT EDIT. PREFERENCES. SERVICES. CHINESE TEXT CONVERTER. DISC UTILITY.” In another work, several websites link to each other in a constant loop: you-talking-to-me.com; well-i-am-the-only-one-here.com; you-talking-me-you-talking-to-me-you-talking-to-me.com; and so forth.

The web collective is also engaged in a project for which they’ve registered one letter domains in foreign languages, including minimal signs like a triangle, or a wave.

Asked about the way in which they employ multiple languages in their work, Paesmans said, “Code is a language, and Joan has been learning languages over and over to make all of these projects possible. It started with developing simple HTML, but then came Javascript, and then ZX Spectrum projects with all of the low-bit games.” Heemskerk said, “It’s easier for me to use code language than a foreign language.” Paesmans said, “Yeah, code is language and the web is bigger than the English speaking language. Especially with the special domain names. We are fascinated by language.”

The pair then showed a piece centering on YouTube, using the now-defunct video response button. Jodi commented on hundreds of YouTube videos at random with a video of Paesman’s finger poking his webcam, each lasting about two seconds. The simple gesture of the finger poke seems to insert them into the net’s stream, minimally asserting their presence in the proliferant text, web, world. Also, like much of Jodi’s work, it’s funny, as response titles like “Re: DO NOT WATCH” appear.

Jodi also presented their iconic website, http://wwwwwwwww.jodi.org/. Paesmans said of the webpage, “We made it in 1995. The whole page was blinking at the time, because the blink tag still existed. The blink tag was just to highlight a little item as new or to catch attention to a small word. Blink tag has disappeared, it’s not part of HTML anymore.”

Jodi then demonstrated an older piece, infamous for crashing viewers’ systems, on Heemskerk’s laptop. Paesmans said in introduction, “This one’s a website made with OSS where we wanted to break the browser totally, because the browser is so close in your personal environment. But it’s still that soft screen or soft layer on top of your desktop. Just to break that layer and then jump from the browser into the personal space was something that we did with this work. It is automatically downloading little software embellishments that show up as black circles. This is also very difficult to stop. I have the first one actually arriving on Joan’s desktop, a ZIP file.”

As the piece begins, desktop icons start to shake and shift to bright primary colors. A mechanical screech commences, and the desktop becomes overexposed as English words morph into alarming non-alphabetical symbols. The whole screen shudders and spins, and one gets the feeling that some line of user compliance has been crossed, and we have entered a new, forbidden domain.

Paesmans said, “Yeah, now we’re going to change computers, because now it gets really too dangerous.”

Jodi took time to answer student questions about their inception. Paesmans explained, “When we started there was no art on the web or net.art, those things did not exist. We were in the States, we were in an art school, and we started to use computers the second year and wanted to continue. Well what else can we do: San Francisco! Silicon Valley, yeah! We got a place at San Jose State University in 1994 or 1995, and the web showed up there in the classroom.”

“So we gave up our CD-ROM experiments and worked in that medium. I was working with video, and video just comes off television. That was always interesting to me, access to a media, a given media, magazine printing, or radio making, or live beats making art. Media outside of the art space or gallery space, if you want. I also hated that video was always a gallery medium and had the whole access disappear, to me.”

“We started to play with the format of a website. We didn’t know what a website was. Accidental mistakes were part of our learning process, and sometimes we just decided that the mistake was much better or at least questioned something that we found interesting. We kept mistakes and kept things that were wrong and did not punish them.

That became just part of the game.”

Jodi taught themselves to use the web, with Heemskerk undertaking the task of learning code with no outside direction. Paesmans said, “Because we don’t have any technical background really, we learned from the open source of the browser. Then we modified, made variations on it. HTML is a real friendly, simple language that you can do all these things with.”

Asked about their relationship to Piet Mondrian, and whether they consider their work formalist, Paesmans said wryly, “A little bit of dirty formalism, maybe. Or it’s surrealism. Something that is a bit sub of the domain description. Pre-post-internet.” Cates said, “You heard it here, from Jodi. #PrePostInternet.”

Paesmans explained of their explorations with the browser bar, “For me it’s quite a strong emotion that after twenty years of web, a lot of the inventors of the HTML language together with the servers are actually calling to save the web. Because you all know what’s going on on the web, on the Internet. You’re not safe anymore. As I see it, the whole series comes together as a tribute to the language of the web, which is, of course, always changing; you could say disappearing, in a way.”

Paesmans continued, “That’s why we are so interested in the address bar. The address bar is under threat. In Safari, they try to win extra visual space in iPads and iPhones. Their address bar doesn’t show the full URL anymore. It just stops by saying you are on CNN.com, and that’s it for the URL you can read. If that continues it could be that the whole address bar is going to disappear. So in that way, the browser could need some help from artists.”

Despite this call for action, Jodi were not totally desparing about the outlook of the Internet and new media. Asked about predictions for the web’s future, Paesmans responded, “I think the Internet will go for a long time, just as television is going and radio has still been going for a long time. But the appearances will totally, have already totally changed, and commercial interests kind of direct the way that the iPads, iPhones, mobiles are slowly replacing a bigger desktop.” Heemskerk said, “There will be more inhuman-built apps.” Paesmans added, “Doesn’t mean that that’s a bad thing.”

Paesmans also explained the history of the net.art movement, saying, “The first group of European artists were more or less five artists after a year or two years, ’95, ’96, ’97. Then there was a physical group of artists that was part of Nettime. Nettime is mostly by a group in Berlin and it’s theoretical, a lot of discussions about the new medium of Internet. A lot of East Europe was very active at that time.”

“On the web, artists were really late to join and to see it, but there was also a lot of design and a lot of coding and a lot of this alternative media. It was a group of artists doing something weird on the Internet. Then, of course, from Nettime up came Rhizome and the center kind of changed into New York, into the States. In the beginning, Europe was more active. But no one in Europe was so intentional that this was a new medium art form.”

Asked what allowed Jodi to do such unconventional things with the net from the beginning, Paesmans said, “I think our excuse, our real chance, is that we were at the right moment at the right place. We were there in San Jose, Silicon Valley, and then with the state university we were connected to that academic circle. So we just recognized it with our previous kind of frustration with video and television as a medium.”

“As an artist, I really like the things we made with Nam June Paik, and even though we call most of his work video art, a lot of it was television programs. He experimented with satellites in the work “Good Morning Mr. Orwell,” a worldwide satellite TV broadcast,” Paesmans said. “That was all possible for Mr. Nam June Paik, of course. The Internet as a technical medium allowed just about anyone to have that worldwide broadcast.”