5 Questions profiles SAIC students and faculty at work, in the school, and beyond. This month, F Newsmagazine spoke with Evan Gruzis. Gruzis is a lecturer in the Painting and Drawing office. He received his BFA in Painting from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and his MFA in Combined Media from Hunter College. He has been exhibited at Deitch Projects, DUVE Berlin, Galerie SAKS, The Hole, The Green Gallery, and other international and national galleries.

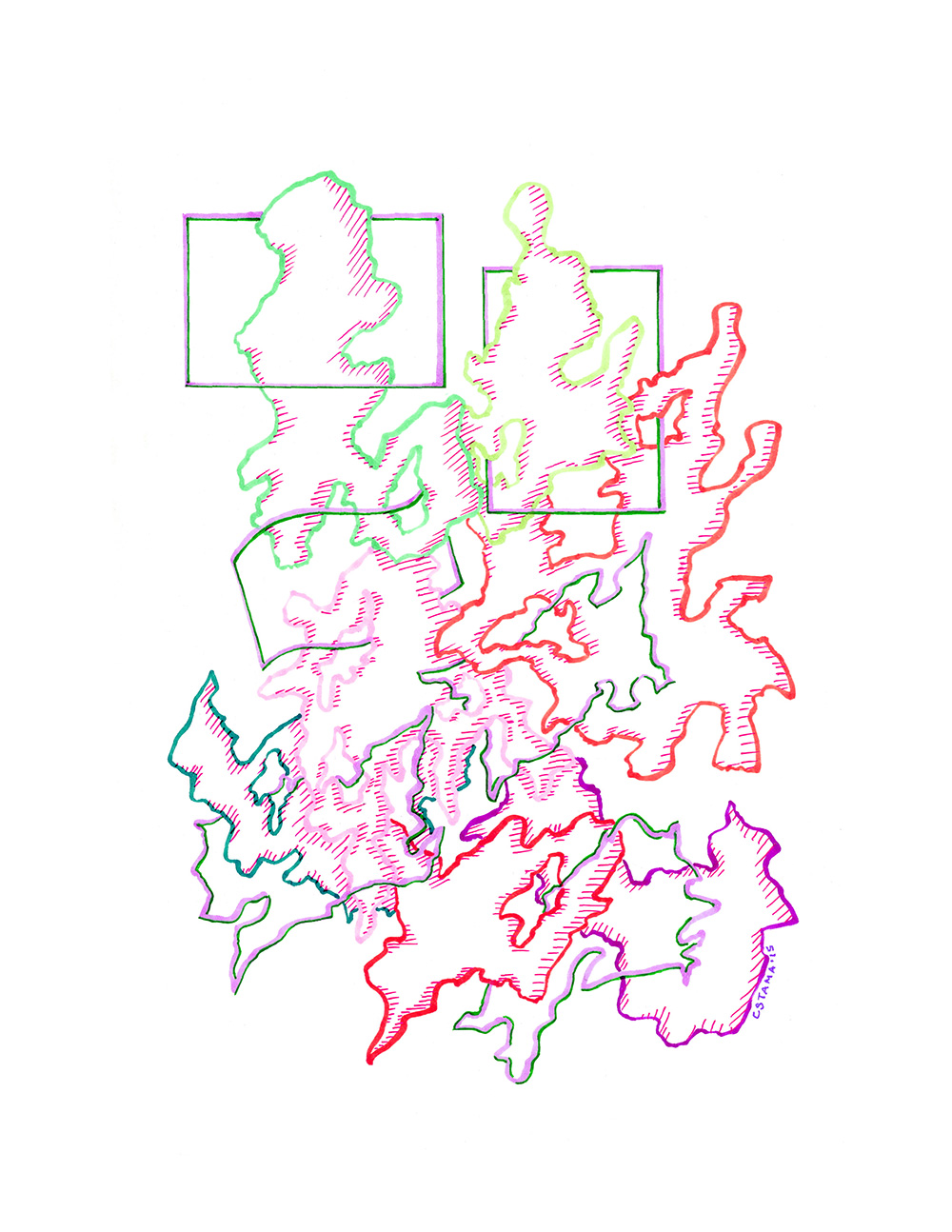

All images courtesy of the artist.

1. The work sets a tone of cynicism and melancholy of Memphis Milano, ‘80s analog, and aesthetics. Is this the initial read you want your audience to have? Could you give the readers a quick thought about your definition of humor and sarcasm?

I would hope that that the initial read doesn’t include cynicism or melancholy, but if that is what you are getting from it I have to respect that. I would hope for more of a self-aware satire, if anything. Intent aside, the human-specific practice of making objects seductive and desirable through visual queues and devices in any context, commercial or otherwise, is evidence of our aspirations for higher states of spiritual fulfillment, or at least new levels of awareness that are not accessed through direct experience. Take the food styling of a Red Lobster commercial, for example. Our point of view is inches from steaming hot prawns that float through the air in glistening slow-mo abandon, kicking up rooster tails of molten butter. This is not a visual experience you can have in your own kitchen; it requires many layers of mediation to exist. It makes the promise of an extra-normal awareness — and all-you-can-eat shrimp. Humor arises when our value systems or ways of comprehension are unexpectedly inverted. I think we are uncomfortable consciously dealing with the absolutes of consciousness in relation to style or commercial desire, and that can make us giggle. I’m trying to show that the transcendent is reciprocally indicated by the entropy of styles as they doppler through time.

2. In previous interviews you have stated that your works on paper are “flat sculptures.” Can you elaborate on this idea, or give us an Evan Gruzis 101 on “flat sculptures?”

This notion has a couple of meanings. The idea first came from a studio visitor who, commenting on my process, pointed out to what lengths I was going to get my watercolor paper to lay flat. My process isn’t unique, but there is an overall ecology of materials involved. One has to have a soaking tank, properly sealed wood of a certain thickness to withstand the shear forces of the shrinking paper, using gravity to create washes, etc. … Boring stuff, but quite the elaborate infrastructure just to avoid wrinkled paper. There are all these material manipulations surrounding the production that could be considered sculptural. Of course, you could say something along these lines about any type of painting process, but it seemed especially poignant in relation to the quaintness of watercolor. The second meaning comes from from a psychological distance that I try to cultivate — this idea that no matter what image is or is not present in a painting, it becomes a prop in the static theater of the gallery. Images, on some level, must inhabit volumetric space.

3. Is there a specific relationship between the meticulous ink layering and photo realism imagery that is represented in the work? Or did they come from two difference places? Why photorealism?

What I do is not photorealism, actually. Photorealism means that a painting is simulating a photograph and all of the traits that come with that: Lens distortion, blur, depth of field, etc. While I use photo references for some of my still-lifes, the surrounding subject matter is invented and not meant to re-create a photographic space. Certainly there is a commercial photography vibe to some of the paintings, but I am very consciously making reductive painterly moves such as not adding depth to the foregrounds and leaving the backgrounds as ambiguous gradients. Maybe this is to the point of your question: There is sometimes an engagement both with flatness and representation in the same image to create an irresolution that hopefully spurs further contemplation.

4. What are the difficulties and challenges dealing with painting history?

One challenge is the obvious one, which is that there always is a danger of re-treading an area of investigation that another artist has covered. Many times contextual interpretations can alleviate pointed criticisms along these lines. However, a context’s ability to deflect criticism lies in its inherent instability, which is why it should not always be relied upon. One difficulty is that history always can be leveraged for critique. The problem for artists trying to transcend history is that an encyclopedic knowledge is necessary to preclude redundancy. So, paradoxically the further we try to get from history, the better we must know it. And the better we know it, the more of an influence it becomes. But, it contains many great lessons.

5. Has moving back to the Midwest changed your process of making art? If so, how?

I think that I’ve been inspired by the spirit of independence and underground experimentation that exists here, apart from the entrenched hierarchies that dominate the various centers. Freedom and silence are available. My process has stayed largely the same, but my thinking is evolving.