This summer, amid the many documented shootings of unarmed black Americans by police officers, another death grabbed national headlines. Samuel Dubose, a 43-year-old black man, was shot during a traffic stop by University of Cincinnati Officer Ray Tensing.

What is remarkable about this event, according to outlets like The New York Times and The Atlantic, is that Cincinnati prosecutors moved quickly to indict, and that the city was able to pursue justice swiftly without riot. Much has been made of Cincinnati’s “Collaborative Agreement,” a series of police reforms passed after great civil unrest in 2001, and how its promotion of racial justice differentiates what happened in Cincinnati from what happened in Ferguson.

A narrative has begun to emerge in the national media, one which heralds the growth and vision of Cincinnati authorities, while glossing over the continuing struggle of predominantly black citizens to draft, legislate, and enforce this Collaborative Agreement. This narrative privileges the mostly white police force, crediting them for shooting fewer black people, as opposed to praising the largely black coalitions who fought for justice. In an effort to understand the true history of the Collaborative Agreement and Cincinnati’s current racial climate, F Newsmagazine spoke with the former president of the Cincinnati Black United Front, Reverend Damon Lynch III.

Caleb Kaiser: In 2001, Timothy Thomas — an unarmed black teenager — was shot by a police officer, and the city erupted in riots. With the recent shooting of Samuel Dubose, the city’s response has been much calmer. What has changed in Cincinnati that has allowed for this difference?

Reverend Damon Lynch III: Not enough has changed, I think. The response after 2001 was just the perfect storm: It happened during spring break, it was an unusually hot April, the city was not forthcoming with information, and it was on the heels of the 14th police killing, which was Roger Owensby in November of 2000. This past summer, with the death of Samuel Dubose, you didn’t have the same perfect storm, but you did have some of the same things happen. Little to no information was given to the community, and when the information was given, it was all negative towards Samuel Dubose. The prosecutor kept the videotape from the community, which did not corroborate the officer’s story, but that didn’t come out until after the indictment of the officer. There were differences and similarities. I don’t want people to think that since 2001 we’ve become much more complacent or peaceful. What happened in 2001 could happen again in 2015

CK: In 2001, you were involved in drafting the collaborative agreement. I was wondering if you could walk us through the history of that, what the process was like getting all the groups organized and then bringing politicians to the table?

Rev. Lynch: We had a number of African Americans in our city who had complaints about being profiled, and then the Roger Owensby death in November of 2000, and of course the Timothy Thomas shooting in April of 2001, followed by three days of civil unrest. There was a lot of tension, a lot of pressure. We filed the class action lawsuit, but we noticed that Pittsburgh previously had the same set of incidents. They ended up with a consent decree with the Department of Justice, but they didn’t have better police-community relations. We wanted to not only come out with reforms that changed how policing was done in the city of Cincinnati, but we wanted a better community-police relationship moving forward. So instead of just litigating the class action lawsuit, which we could have of done and I’m sure we would have won, we decided to do a collaborative effort which brought together community representatives, the city, the FOP (Fraternal Order of Police) as well as the justice department, under the oversight of a federal judge. It became a community-driven process. 3,500 people in our city came together to figure out how can we not only have better policing, but better community-police relationships.

We brought in the FOP because usually the rank-and-file are not at the negotiating table. They’re usually represented by the brass, but we understand that no matter what brass says, it’s the rank-and-file that have to be out on the streets. The city wanted to fight us. One [council member] who’s no longer there but still fighting us, Phil Heimlich, said, “Hey, let’s just go to court. Let’s not go to the table.” As for the police, the brass didn’t want to come to the table, the FOP had to vote whether or not they would come to the table, but in the end everyone came because there was so much going on. We had the three days of unrest, and we had an economic boycott of the city. Bill Cosby, for whatever his issues are now, was the first person to say, “I’m not coming to Cincinnati!” He pulled out, Whoopi Goldberg pulled out, and major conventions pulled out. There were a number of things happening: You had an economic impact on the city, you had a federal lawsuit against the city, and we continued protesting day and night against the city.

They finally came kicking and screaming under the oversight of a federal judge that kept everyone at the table. There were many times the city tried to get us removed from the table because of the boycott. They said, “How can we work with them when they’re putting the financial pressure on the city?” The judge said, “Hey, too bad. This is the group that filed the lawsuit against you.” We kept the pressure on, we kept the protest on, we kept the boycott on, and we sat at the table and negotiated. We engaged the entire community. There were a number of different ways people could have engaged, online or in small groups, but it ended with 3,500 people giving input.

There were three parts to it: There was the problem and the perception of racial profiling, there was the collaborative process, and there was the product — the Collaborative Agreement. What I challenge other communities to do is to not skip the process. All of us — Baltimore, Ferguson, Cleveland — are facing the same problem, which is that black communities are over-criminalized, over-policed, and that police brutality exists. We could all get pretty much the same product, call in the DOJ and they’ll do a “Patterns-or-Practice” investigation, and then we’ll have reforms, and then we’ll have a product. If we don’t go through the process, we still have acrimony, but we don’t have the community-police relations that are ultimately necessary.

CK: You’ve talked a lot about the community coming together, and different organizations pitching in. Have those organizations sustained themselves over the last 14 years in the Cincinnati community?

Rev. Lynch: The hard part about a community-driven process is recognizing that everyone at the initial table was there because they had to be or they were paid to be. In the case of the city and the police, they were made to be there, and the hammer was dropped on them. The community, we were there because we wanted to be. We felt the need and urgency to be there, but to keep the community engaged over 14 years is not easy. People move on with their lives. We’re not paid activists. Unless there’s some Sam Dubose moment or other cataclysm, you can get lax and just believe that people are doing the right thing.

I think where we are in Cincinnati after 14 years is needing the community to re-engage, go through the agreement, and start to make sure people are being held accountable. We have a Citizens Complaint Authority that we fought to get. It has investigatory and subpoena power whenever incidents happen, and I think we’ve learned they haven’t been doing all that they could be doing. There are supposed to be five investigators, but they went down to three and now there’s a backlog of cases.

The agreement talks about reviewing the footage from dash-cams, I’m not sure we’ve done that. There needs to be a group that at least once a month just goes through dash-cams, that lets them know they’re still being held accountable, there’s still expectation, and they’re still being watched. If they are doing everything they should be doing, which I doubt they are, then that’s fine. If they aren’t, there’s some blame the community needs to take, because we’re the ones who are supposed to hold them accountable.

CK: Dovetailing from that, 14 years since the agreement first passed, what amendments would you add?

Rev. Lynch: Well, we have added to it. This agreement is not holy scripture. We wrote it to the best of our ability at that time. When we wrote it, Cincinnati police did not have tasers, so there’s nothing about tasers in the agreement. We’ve since added to the agreement about the use of tasers because we had people being tased in our city and dying from it. Right now everybody is talking about body cameras. Our officers don’t yet have body cameras. We need in the agreement who’s going to be the custodian of the cameras, custodian of that information and when it will be released to the public. Our police force right now is not as militarized as what I saw at Ferguson. If that becomes the case, that’s something we’re going to have to address in the agreement.

CK: This is a bit of a change of topic, but with the gentrification of Cincinnati, has there been a new set of problems with community organizing?

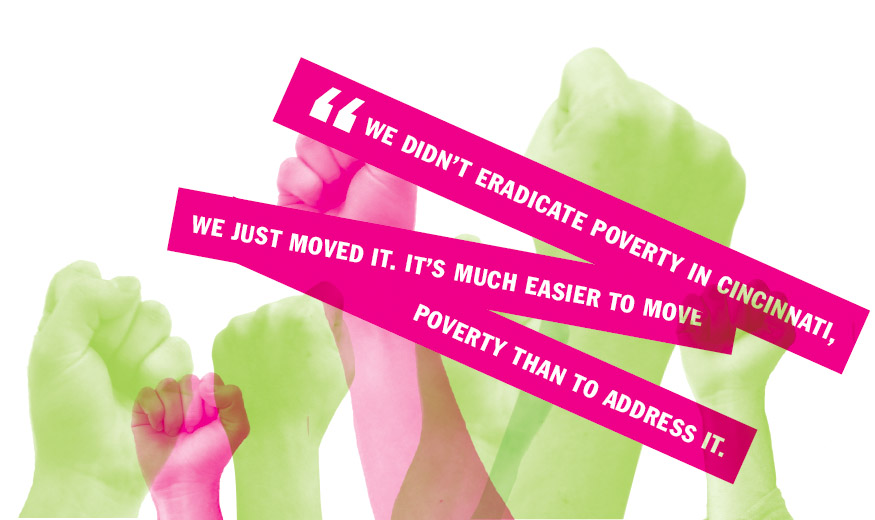

Rev. Lynch: The landscape was changed after 2001. After the unrest in 2001, while we won the battle on policing, we lost the battle on economics. The gentry — the gentrifiers — saw an opportunity to come in and do what they wanted to do for the last 40 years, which was take the neighborhood from people who live there. There has been a mass exodus of the people who live in poverty from the community, a mass exodus of the social services that engage the people in poverty, and now you have microbreweries, sushi bars, and other things that some people think is the greatest things since sliced bread. It has been touted around the country as a great success story, but people don’t look at the underside of the quilt, the people who had to be displaced, the people who love their community. We didn’t eradicate poverty in Cincinnati, we just moved it. It’s much easier to move poverty than to address it. That to me is one of the painful parts that came out of the 2001 rebellion.

CK: Do you see any connection between the University of Cincinnati police being given license to patrol off-campus and efforts to gentrify poor neighborhoods?

Rev. Lynch: I saw that as a reaction to students being robbed and beaten. The University was trying to protect its students and they sent officers into the surrounding community who were not well trained, who I’m sure had very little or no training on implicit bias, and they just went out and started stopping black people. If you look at the numbers recently, their stops went through the roof. I think like 86% of them were pulling over African Americans, and it ended with the death of Samuel Dubose. This is actually the fourth death they’ve had that I know of.

CK: Final closing notes?

Rev. Lynch: Right now America is seeing that there is still a race issue in this country. I think studies are showing that even whites are saying, “Yes, America still has a racial issue. This is not a post-racial society.” One black family living in a white house didn’t change everything.