Illustration by Jordan Whitney Martin

The Economics of Professorship

When college enrollment and tuition are at all time highs, how could professors sometimes be paid less than grocery store workers, forcing them to take jobs teaching at more than one university? This is an unfortunate reality of part-time professorship in the United States. According to the American Association of University Professors, the average salary for a part-time faculty member teaching a three-credit course is $2,700. So to do some simple math, an ideal adjunct professor (another way of saying a part-time professor,) would teach four classes per semester putting their annual income at about $21,600.

Ian Weaver, a former part-time unranked instructor at SAIC whose work is currently on display at the Chicago Cultural Center said, “The myth of ‘flexibility’ as an adjunct is just that: most of my graduate friends who are still adjuncting are all over the place, literally traveling from institution to institution. It is draining. It never really leaves you time to make your work.” He now teaches full-time at Saint Mary’s College in Indiana where he has “time, space, financial security, and health benefits, which makes creating work much easier. It is a sustainable way of life; adjuncting really isn’t.”

This explains why you see articles written about part-time faculty on food stamps, so entrenched in poverty that there seems to be no way to balance teaching and making a living wage. The Campaign for the Future of Higher Education reported that contingent faculty, or faculty off the tenure track, are sometimes hired two or three weeks in advance for a course they will teach, leaving little time to plan and forcing faculty to spend far more time on the class than they are paid for. This then cuts into time for their own research or ability to hold another job, and, of course, the amount of time they can spend on class preparation.

In 1970, part-time faculty represented 22 percent of all teaching faculty. In a survey taken in 2011 by the National Center for Education Statistics part-time faculty represented 50 percent of that population. This means that half of professors, who now work part time, do not have the same benefits as their tenured colleagues. Part-time teaching increasingly poses a threat to all faculty’s academic freedom, faculty-voice (the ability for part-time faculty to have power or be listened to by an administration), job-security, benefits like health insurance and pensions, and even allotted time for research grants — not to mention to the quality of students’ educations. All of this while college tuition has risen 439 percent from 1982 to 2007.

There is no doubt that approaching the university as just another business is a compelling notion for administrators. But the idea of part-time faculty as expendable employees whose hours and classes can be cut and whose benefits can be denied seems strange coming from an academic institution. This mindset only makes sense if we think of institutions of higher learning as if they were for-profit ventures.

What SAIC Is Doing Right

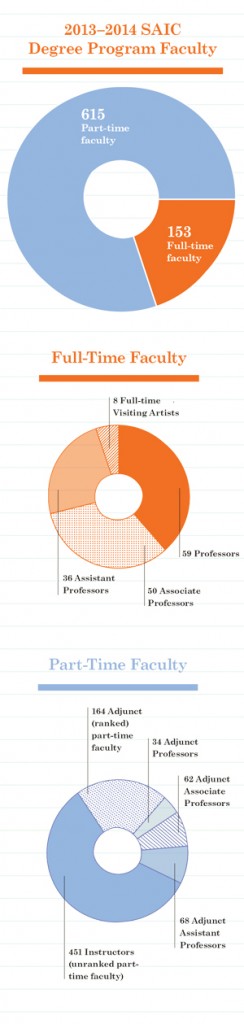

At SAIC, part-time professors are divided into two groups. Adjunct faculty (adjuncts professors, adjunct associates, and adjunct assistants) who are part-time but are eligible to receive benefits and contracts. Lecturers are unranked, receive no benefits, and do not receive contracts. The difference between the two groups is that on adjunct professors teach more classes, and as well have contracts and benefits. In response to the concerns of the small, attentive community of teachers and administrators at SAIC, the administration recently announced a new report titled Part-Time Faculty New Initiatives that would further their vision for what the SAIC administration should do for it’s faculty. The report calls for greater compensation and stability, professional development, and shared governance for part-time faculty.

The per-course rate is slated to rise approximately $1,000 in each part-time category by the 2018-2019 school year. Part-time teachers will also be compensated with a course cancellation fee of $500, which is intended only to compensate those lecturers for time spent planning for their courses, not for the courses themselves.

The report lists a Merit Review Raise Program for lecturers who have personal and significant achievements; they can apply for higher per-course rates depending on their status at the school. The report also states that part-time faculty who act as substitute teachers, participate in admissions, or take on short term administrative responsibilities for the school will have their current $200 day-rate raised to $250.

The advancement section of the report states that more than a third of full-time hires in the past five years have been adjunct faculty already familiar with the cultural climate at SAIC. Undergraduate Dean Tiffany Holmes told F Newsmagazine that former adjunct in the Art and Technology department Judd Morrissey had been promoted to a full-time faculty position in 2014. The report mentions more promotions and job growth in the coming years.

Perhaps the most impressive of the new initiatives is that unranked part-time faculty and adjunct assistant professors “may be eligible for written contracts for terms of two years. Adjunct associate and adjunct full professors may be eligible for written contracts for terms of two or three years.” This as well as providing adjunct professors with benefits make SAIC’s faculty employment policies progressive. Other opportunities for development include a new elected position, the Chair of Faculty, who will be responsible for “ongoing development of all faculty.”

The report does a lot for the morale of part-time faculty at SAIC and signals that the administration wants to hear their concerns.

Why Not Hire Full-Time Professors?

“Sometimes I think we are forgetting what we ask part-timers to do,” said Sonia Da Silva in her office in early February. She talked about how difficult it was to get her team, who are exclusively part-time unranked professors to meet up because of their conflicting schedules. She and her team found a way around the challenging and inescapable nature of the contingent faculty schedule while maintaining a focus on their students education. “We made a wikipage, so that we can talk about the students and see what we need to do for them,” Da Silva and her department are only one example of the incredible part-time faculty at SAIC. In fact, SAIC awards one part-time faculty member a year with an outstanding achievement award, nominated by students. Some of the past recipients of the award, who are part-time, include Irena Knezevic and Trevor Martin.

SAIC’s strengths point to a strong business acumen and effective administration, but there is a disconnect between a sort of efficacy in the school addressing administrative issues related to part-time professorship and its lack of attention to the effects these issues have on the sustainability of part-time faculty, students, and overall scholarship at the institution.

Supervision is just one of the curious things that have problems at a school which holds such precision when it comes to administrative issues. One example is the case of an undergraduate course in the Art and Technology department. The course, called Fabricating Promotion, focused on using different types of motors, and studying anything involving movement.

“The syllabus was very open to final pieces as long as they incorporated movement,” one student said. “At the beginning it was promising, the teacher seemed relaxed, but it started to feel disorganized after the first few weeks.”

The instructor stopped arriving in class on time and pushed its start time from 9 a.m to 9:30 a.m. Sometimes the instructor showed up far later, even past 11 a.m, with students not only waiting for two hours but paying tuition money to do so.

“I had been hearing from the students because they did send me an email, and I looked around and talked to my staff who facilitate the rooms and I got some cooperation that the class was not going well, so I went in to look at the class … and we did not ask that instructor back,” said Peter Gena, the chair of the Art and Technology Department. Holmes said, “What’s interesting about the question of supervision is, I think this is something we could do better at. We could use fresh eyes or a new perspective.” A new perspective seems sorely needed.

Two confirmed students e-mailed Gena about the course asking for solutions to the course. In the context of school policies, they were provided with two options: to take the credit, or to be refunded tuition for the course and receive a ‘W’ for withdrawal on their transcript. In this absurd dilemma these students can either accept the refund they deserve with an unwarranted blemish on their academic transcripts or quietly accept credit for a course where the skills and knowledge promised were not provided. This reflects an understanding of course credits as a marker of monetary value rather than academic growth, and the broader implications of such business-oriented thinking are seen in the school’s handling of part-time professorship.

“I’m not happy with it. 70% of courses taught are taught by part-time faculty, and that has to change,” commented Lisa Wainwright, Dean of Faculty at SAIC. Of those part-time professors, 164 are adjunct professors, or ranked professors, and 451 are unranked part-time faculty, or Lecturers. For as long as the faculty members interviewed by F Newsmagazine for this article can remember, they have understood Wainwrights’ was to have 50% of courses to be taught by full-time faculty. “It’s very challenging in terms of budget,” she said, “because to have new full-time positions is a big hit to the budget.” While the cost of full-time positions is indisputably higher than the cost of part-time positions, whether the money simply isn’t there seems up for question.

When discussing a school whose business acumen is so finely tuned that late-fees at its media center are charged by the minute; that a substantial number of its students are not U.S. residents and ineligible for financial aid; that one three-credit course costs $4,314; it seems incredible that the obstacle to the growth of full-time faculty would be cost.

The overreliance on part-time faculty affects SAIC students, as well. What reverberates through the interviews F Newsmagazine conducted with multiple professors was that alongside the countless incredible part-time faculty members at SAIC was that “there seems to be a good deal of instructors hired to teach courses for which they don’t have sufficient pedagogical training,” said an Adjunct Professor who wishes to remain anonymous.

Where this seems to be particularly felt is in the First Year Seminar courses, which are supposed to act as an introduction to composition through an array of courses ranging from Marx to Fight Club. The problem with hiring lecturers for First Year Seminar classes, and perhaps the reason undergraduates file numerous complaints on course evaluations about those lecturers each year is, according to Holmes, that “the teachers are often hired as Ph. D. candidates who may not be accustomed to teaching first year art and design students basic writing skills … they don’t have a lot of experience with composition and their heads are wrapped up in the dissertations. There’s sometimes a bit of a miss … because some syllabi are aimed at a much higher academic level.” In this way, First Year Seminar is an oversight of what is supposed to be a sort of freshman composition course. Here, it is because freshmen are asked to write for example, an exegesis statement without ever really knowing what one is, they have to find help outside of the classroom. They often find that help at the writing center, which is a graduate operated facility that helps undergraduate students understand academic assignments such as exegesis. In this way, the role of teaching what an exegesis actually is often falls onto graduate students.

Graduate students are hardly paid the same amount as the teacher who should have been facilitating this work in this first place, but was never mandated to. Even after considering the negative effects of this on the graduate student and the professor, one must consider the consequences this has for the students. Instead of learning composition in the three-hour lecture (which supposedly serves as an introduction to academic writing), the student is left to learn the fundamentals an exegesis — writing on their own, outside of class.

Addressing this problem is not as simple as hiring one incredible professor or chair—it requires the administration to address the problem of part-time faculty as a whole. It requires that idealism Wainwright is hoping for to manifest in the way that the school treats its part-time faculty, which for the most part, is far better than other U.S. universities.

“I do consider adjunct faculty part of our core faculty. Do they need better pay and more opportunities? Yes, they do,” Wainwright said, stressing that part-time faculty were part of the foundation that makes SAIC one of the best art institutes in the nation. Gena may have said it best: “I would put our faculty against any other faculty out there.” Gena, here, is right. The part-time faculty at SAIC have been lauded with awards from artist communities nationally, as well as exhibiting outstanding praise from their own students.

So how, if everyone at SAIC is aware of the value of those who provide and facilitate the learning that makes SAIC and so many other schools so great, is there now room to cut superfluous spending, or redistributing money to reasonably compensate the faculty teaching the students? In the case of SAIC, how can the cost of tuition be so high, and not reasonably allow for granting more part-time faculty benefits and full-time positions?