An Unconventional Motivational Speech

Wafaa Bilal’s Making the Invisible Visible lecture opened the Spring 2015 series of Visiting Artists Program talks at SAIC. Bilal is a successful interdisciplinary artist who works primarily with art and technology and includes performance, video, and sculpture in his practice. As an Iraqi-American, he uses art to commemorate casualties of the Iraq War (2003-2011) and to provoke dialogue about violence and prejudice.

Bilal is more than familiar with SAIC: he is an alumnus (MFA 2003) and also a former professor. His honesty and sense of humor received a positive response from the audience that gathered on that day, eager to learn how he was able to make art in a refugee camp and why he wants to send Saddam Hussein’s golden bust into space.

At the beginning of the lecture, Bilal shared some dramatic experiences from his youth. They shed light on his motivations to make political art, and on his persistence in developing his often controversial ideas (such as allowing internauts to vote whether he or a dog should be subjected to waterboarding). Growing up in Iraq, he was denied an entry to the College of Fine Arts in Baghdad because of his family’s political involvement against Ba’ath regime. While studying geography, he organized shows of his art. His pieces, criticizing Iraqi political situation, were often confiscated by the police. After inspiring his fellow students not to join the voluntary army service during the war with Iran, Bilal fled the country and spent two years in a refugee camp. Even there, he continued to make art. He found a job as a trash-collector and paid local truck driver to smuggle paint into the camp.

Bilal’s current position — a successful artist and a college professor at New York University — seems like a fulfilment of the immigrant’s American dream. However, it must have been difficult for the artist to be a citizen of two countries at war with each other. His brother was killed by a U.S. missile strike.

Bilal’s art is controversial and he sometimes had trouble finalizing or exhibiting his projects, especially Dog or Iraqi (2008) and Virtual Jihadi (2008). Dog or Iraqi was a participatory piece in which the audience was invited to vote online to choose whom between a dog and Wafaa Bilal should be subject to waterboarding. This artwork investigated the issue of torturing terrorism suspects. It was boycotted by PETA, because “they really believed that I would waterboard the dog!”— explained Bilal with an amused smile, causing laughter in the audience. Another controversial piece by Bilal is Virtual Jihadi, a modified version of Quest for Saddam and Quest for Bush. These are two video games displaying harsh stereotypes about both the American and Iraqi communities in which the player tries to shoot either one of the political leaders. In Virtual Jihadi, the artist created an avatar for himself, representing him as a suicide-bomber on a mission to kill the American president. The goal of this controversial piece was to denounce political propaganda and violence. The game was criticized by some American students and politicians as anti-patriotic (they clearly misunderstood Bilal’s intention and opted for a literal interpretation of the work) which led to the closing of the show. It reopened after protests of Bilal’s supporters.

Despite difficulties and harsh criticisms, Bilal does not hold negative feelings towards opponents. He is grateful for their contribution to the discussion provoked by his art. During the lecture, Bilal never seemed to complain about his difficult experiences. He explained that making art helps him to cope with negative emotions. His upcoming project Canto III — sending Saddam Hussein’s statue into space — is an unfinished idea of Hussein’s party, re-contextualized by Bilal in order to symbolically “exile” the dictator. Working on it allowed the artist to be freed from the anger he has felt for many year against Hussein.

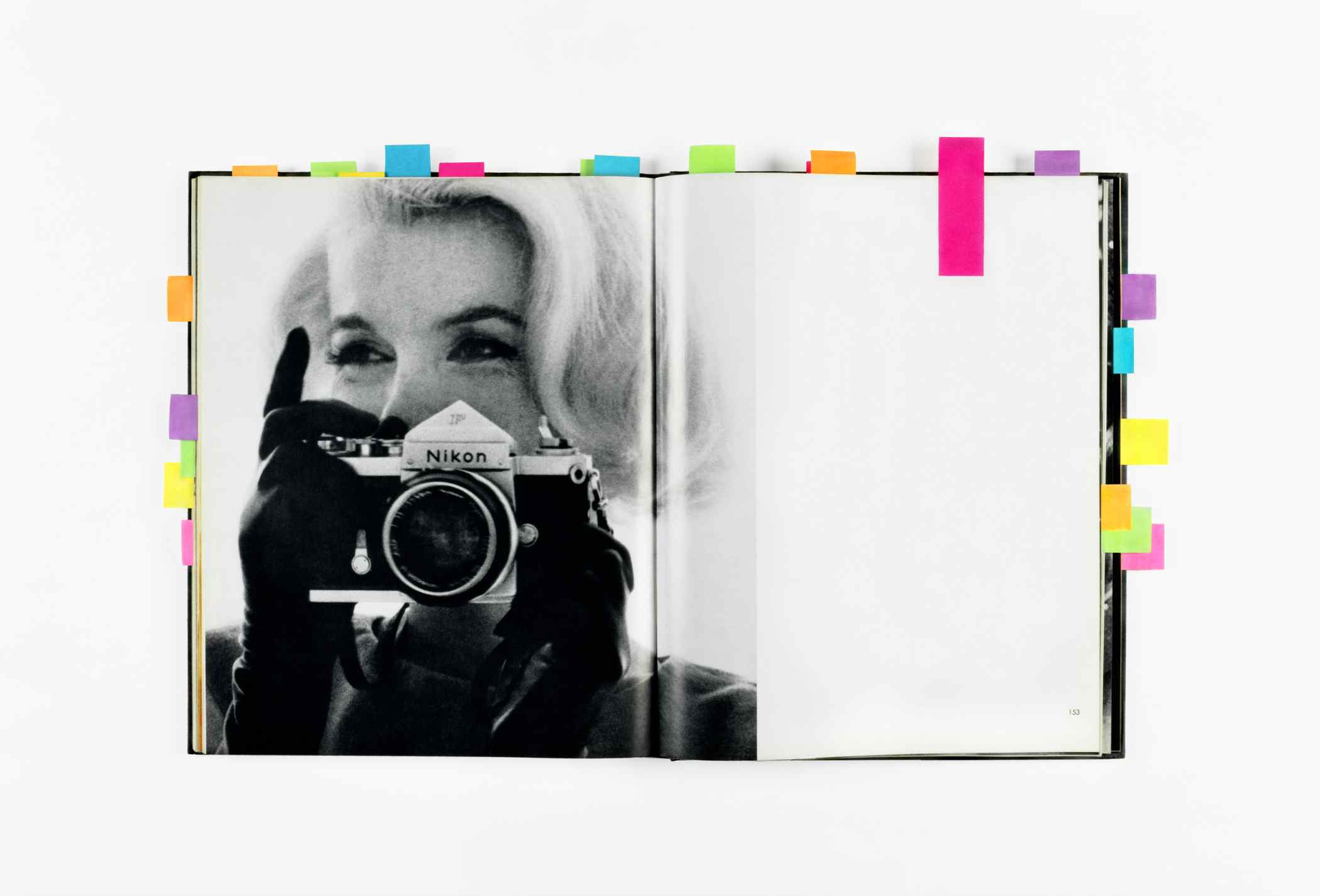

Bilal pushes his own body to extremes in order to achieve his artistic goals. In the project and Counting… (2010) that commemorated the “invisible” (not spoken about) Iraqi war casualties, Bilal had his back tattooed during a 24-hour performance. The artist also had a camera surgically attached to the back of his head for 3rdi (2010-11) a project that documented his daily life through automatically taken photos. Dog or Iraqi (2008), was prompted by Bilal’s curiosity regarding the form of torture known as waterboarding. When asked if he had not feared that the experiment might be dangerous and potentially lethal, he humbly responded that him being tortured was just a project that involved safety methods, whereas true victims of waterboarding are not protected in such ways and sometimes actually die.

Bilal’s art deals with both personal and national trauma through humor, risk, interactivity, dialogue, and symbolic commemoration. The artist’s goal is to visualize the “invisible” topics that the society does not talk about, for example the number of civil casualties in the Iraq War. Although Bilal uses the specific context of the Iraq War (2003-2011), his art remains universal because of the topics that he addresses. Bilal deals with harsh personal experiences and social issues that are important to him, yet manages to make them relevant to many audiences.

During a roundtable discussion that took place after the lecture, Wafaa Bilal was asked what advice he would give to art students. He said: “Don’t worry about sales and galleries. Do what you like to do and most importantly do not have any breaks in your art practice because one project most often comes from another.” Such an advice, coming from someone who was able to continuously make art in a refugee camp, could well be the best motivational speech for young artists.