Paranormal Photography: Shameless Fabrication or Truthful Transparency?

All images from the Library of Congress

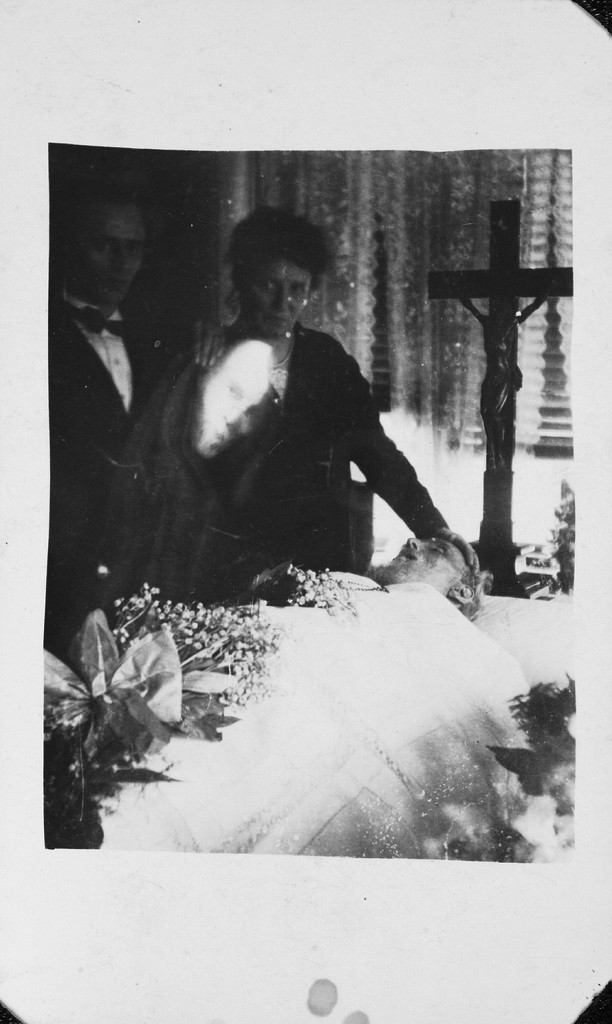

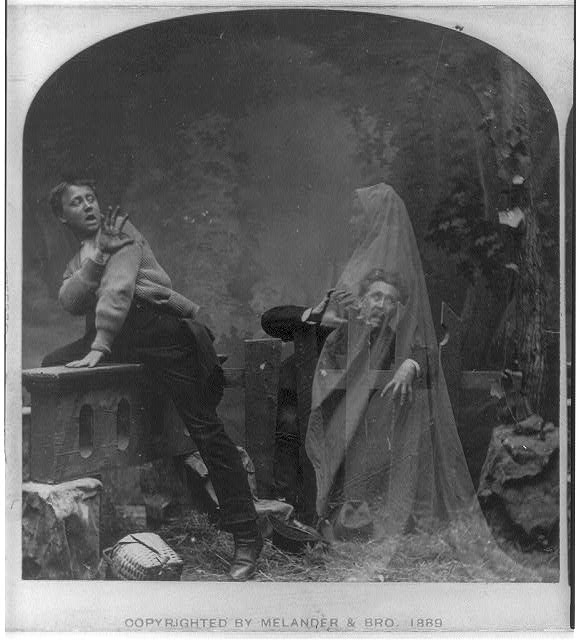

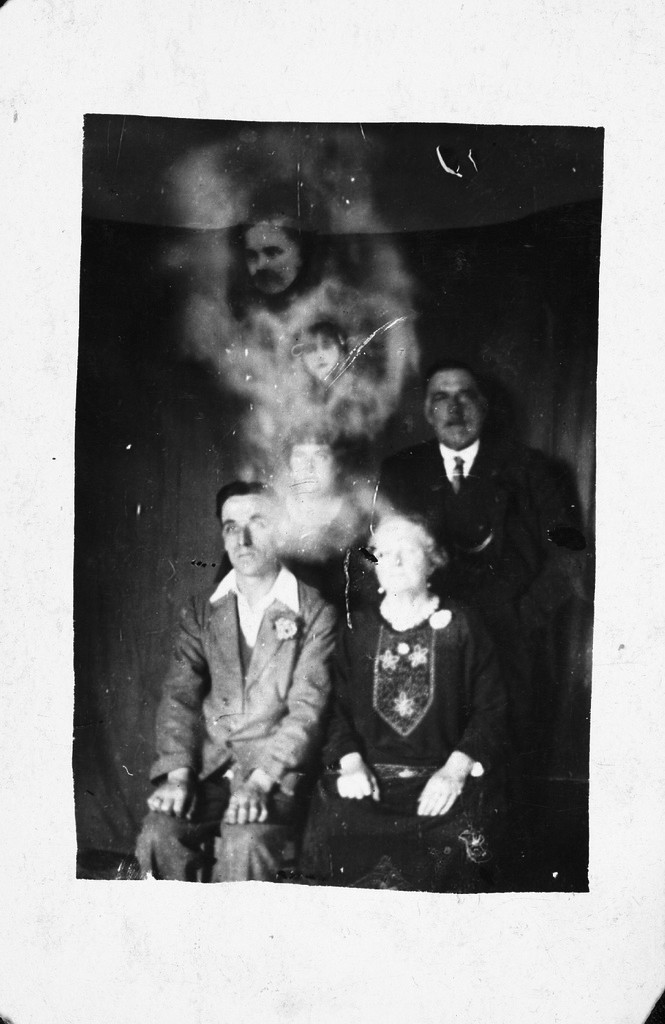

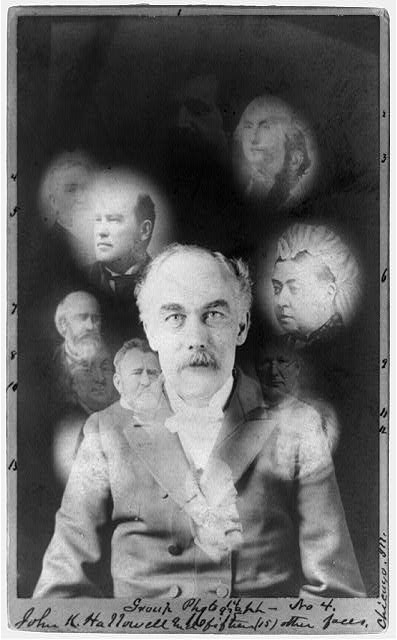

Initially heralded as the epitome of honest representation, the camera is ideally a neutral machine with which to disseminate objective images. Yet photography as a medium has destabilized our collective conception of truth and deceit, given the image’s ripe potential for both digital and manual manipulation. Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, for example, double exposure was readily employed by so-called spirit photographers — charlatans who “conjured spirits” into pictures by placing deceased friends and relatives, via procured film plates, into expensive portraits for surviving members. Yet while Victorian era mediumistic photography and its contextual cultural climate is thoroughly documented, it is still worth considering what makes certain historical and modern paranormal photographs believable, and which of their elements viewers find deceitful or telling.

Determining the legitimacy of documented apparitions involves counterintuitive logic: perfection — and expertise — both become suspect. A manifestation too sharp or unmistakably human may be fraudulent, and one too abstract dismissed as a film processing error. The most compelling paranormal photographs are either those whose apparitions evoke human form though do not seamlessly reflect it, or those that contain a sinister abnormality deemed beyond the scope of mechanical error. Ideally, such photographs are taken by novices who unwittingly caught a spirit on film through the course of depicting an everyday event. The most valuable photographs are happenstance miracles, making paranormal photography a rare instance where laypeople are believed far more readily than experts.

To believe in ghosts is to immerse oneself in a soft counterculture which, though arguably irrational, is still not quite too bold. Like religion, paranormal beliefs benefit from a long-standing cultural reification, and both rely on rare yet powerful terrestrial manifestations for justification. In particular, the paranormal’s lack of institutionalization means that the need for phenomenological proof is significant. Photographs are its testaments, yet the photograph as a persuasive medium embodies a precarious position between truthful transparency and shameless fabrication. Out of the thousands likely taken, only some ten paranormal photographs have stood relatively unflinchingly up to scrutiny. In the event that an unusual apparition surfaces within a roll of film, its legitimacy is thus gauged immediately.

Spotting the spirit in more ambiguous photographs is an exercise of faith which echoes the exaltation of mundane phenomena as religious signifiers. A rough decade ago, the Virgin Mary’s likeness surfaced on the derelict wall of a Chicago highway underpass, evoking a sense of awe within some Chicago residents. Adorned with candles, flowers, and the Virgin’s iconic painterly rendering, it is almost implicitly suggested that a visitor might need a juxtaposed reference to detect anything other than a semi-solid drip that flows down toward the sidewalk from an invisible hole in a concrete wall. Yet this is hardly the first instance of religious iconography turning up in odd locations. The trend is prevalent enough to boast an awkwardly titled Wikipedia page.

Paranormal manifestations across all spectra typically reflect the spiritual and aesthetic values of a given period, which in turn are subject to change over time. We see what we want to, or what we are told we should. Perhaps to prevent our sense of subjectivity from collapsing into chaos, we draw our own lines between which visual double-entendres are plausible or unreasonable, thus policing our ability, so to speak, to see everything. The predisposition for locating faces and figures in otherwise mundane objects or locations is known as pareidolia: optic research suggests that we construct images as we wish to perceive them, naturally taking into play religious upbringings or underlying propensities for supernatural belief. Sinister shadows, orbs and echoes of almost-faces and hands thus embody subjective viewership at its most potent. The question shifts from whether a recognizable specter has been artificially constructed to the degree an errant blot or swirl indicates anything suspicious at all.

Specially embroiled in both the camera’s propensity for error and the debate over what should attain paranormal significance are orbs, ghost’s simpler underlings. Strictly speaking, orbs are nothing more than wavering balls of eerie light or, as their devotees assert, concentrated manifestations of spectral or spiritual energy. Orbs are often shot amongst headstones, simultaneously enhancing their allure and desperation, given the cemetery’s power of place and ability to make any visual anomaly suspicious by association. Whereas professing a belief in ghosts is somewhat commensurate to believing in the Resurrection (nonsensical, yet culturally supported), orbs positioned as paranormal phenomena are subject to more scorn than intrigue. They are the weakest proof, the proverbial Virgin Mary floating over Fullerton Avenue. Orbs are also modern inventions, wholly dependent on the digital camera’s advent for their existence. Since fringe believers desperately flip such rhetoric by offering that orbs existed invisibly before digital capabilities, orbs further dismantle an already erratic understanding of the camera’s truthfulness. Perhaps they amplify the human eye’s inadequacy, and the camera’s dead, neutral stare really can discern apparitions we have been missing all along. Then again, nine times out of ten, they look an awful lot like dust bunnies.

Why are such phenomena so fervently and bitterly contested to begin with, and what gratification their existence offers the believer? To profess or deny supernatural belief is to make a statement on the energetic structure of life — whether a portion of our energy transcends into spirit or dissolves shapelessly back into the environment, bearing no mark of its former body. It is, boiled down, a variation on the constant yet unanswerable question of an afterlife, of dimensions beyond our own.

Sifting through paranormal photographs, a strong underlying thread is our desire to prove continuity — to gratify oneself with evidence that there are more strings in the universe than we might initially think. It is as though we crave reassurance that at any time, we could be surrounded, watched; a strange and discordant reversal of our alleged desire to see everything in front of us for what it really is.

Title illustration by Allison O’Flinn