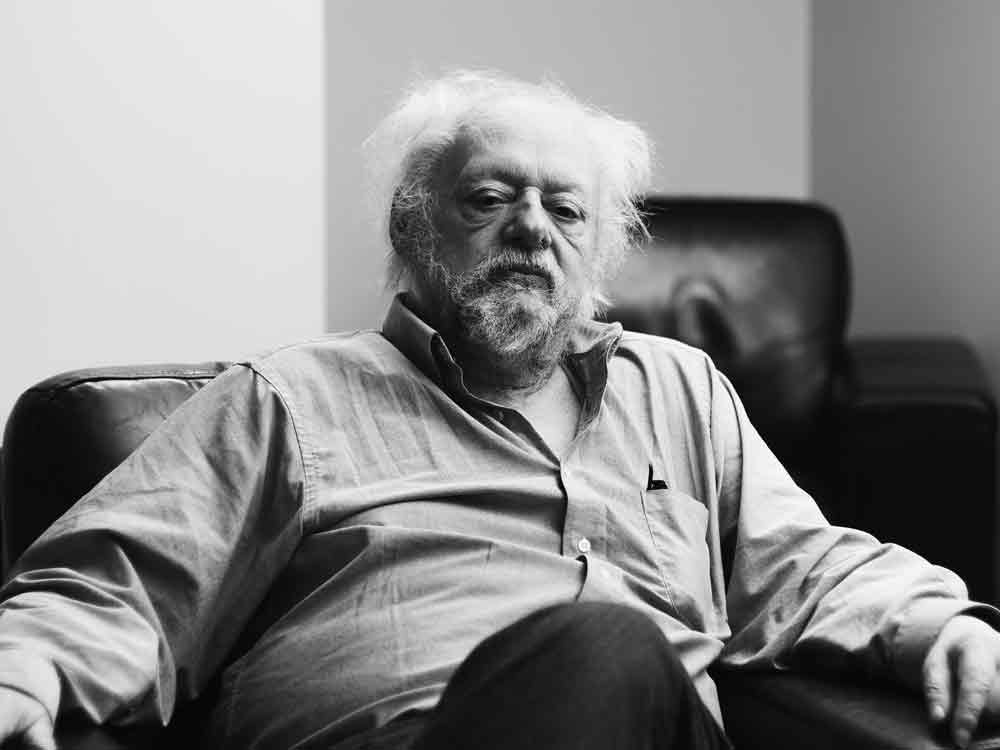

An interview with New Art Examiner co-founder Derek Guthrie

Pablo Lopez: In 1973 you were fired as an art critic from the Chicago Tribune; there was “under-the-table censorship” occurring, as you called it in your introduction to the recent New Art Examiner (NAE) Anthology. Chicago, by many accounts was a cultural backwater. Why not just move to New York and fall in with like-minded individuals in a thriving art scene? Why did you stay in Chicago and found the NAE?

Derek Guthrie: No explanation was given [for being fired]. After that event Jane and I wrote a story for Art News on the Imagists going to the São Paulo Biennale. It was received with great enthusiasm, and the editor, Milton Estrow, called and said it was so good he was going to run it a month early. It never appeared.

The ad rep for Art News told a gallery owner the story was lifted off the galleys three days before publishing, as a number of people called Art News and threatened an advertising boycott. The ironic conclusion is that the editors of the anthology The Essential New Art Examiner included the same story not knowing of the previous censorship. The boycott was a professional assassination. We could not go to New York, as Jane had a young daughter who recently had started school and did not need her life to be rearranged at that time. We also had some support from artists and community members who encouraged us to set up the New Art Examiner. Jane had a belief in community, inherited from her great aunt Jane Addams. I am sure the same people who got to Art News also got to the Tribune.

In November 1974 editors of the NAE wrote “the Examiner is meant to be a forum for artists and thrives on controversy.” Did it succeed in being a forum for artists? Do you think the controversy that it invited assisted it or hampered it in

that aim?

We never looked to be controversial. As I said, the offending article is not seen today as offending. It is well balanced, well-researched, and professional. The NAE promised and lived up to that promise: equal space to any artist to refute or challenge any reviewer. The Essential New Art Examiner bears witness. The editors included two polemical articles by the late Frank Panhier, who argues with gusto for a place for Chicago abstraction. Chicago is crude with a dismal political and social history. Though life was difficult, the NAE “thrived” on controversy as it survived. Simply, we believed that Chicago, a major city, should have had room for more than one expression in art. The history of the NAE has to be written. Evidence will show that the NAE was more than happy to include diverse opinions. If independence means one is controversial, that is a Chicago legacy and a truth which, in my opinion, keeps the city as a provincial backwater.

It is well documented that you have been a controversial figure in Chicago, relative to art and criticism, and as a result you have been marginalized to a certain extent by some Chicago art institutions. Why is that?

The marginalization is due to fear. The same fear that Nelson Algren speaks to when he wrote the 1951 essay Chicago: City on the Make. When the NAE passed into other hands after Jane and I retired, the new editor and board removed the original slogan, “The independent voice of the Visual Arts” to be replaced with “the Voice of Midwest Art.” We were listed on the masthead as “publishers emeritus,” a fancy title that meant we could no longer write for the NAE. The magazine became a respected national art publication, the largest published outside New York. We took on and challenged the big three, Art News, Artforum, and Art in America, with a shoestring budget. The Chicago art establishment had to shun us. No longer were issues of art important; the power struggle is always dominant in Chicago.

What, in your opinion, will be the legacy of both the Chicago Imagists and the Hairy Who? Do you think the work of those artists have the power to stay relevant?

Leon Golub was a Chicago Imagist of the generation after the war called the Monster Roster, which preceded the Hairy Who. He and Ed Paschke, believe, have staying power, as does the later work of Jim Nut, which I have not seen much of. The legacy of the Hairy Who is that they embraced, before most, the manner and mannerisms of commercial art, presenting a mistrust and rejection of the high-minded abstraction of New York, connoisseurship of lowlife art through a camp sieve. I sense Paschke was substantially different in that he used painterly space as opposed to diagrammatic graphic space or reliance on decoration. I see him as dealing with the human behind the facade of costume. This humanism, or sympathy, links him in my consideration with Golub.

Contemporary art is an intricately balanced complex of financial, intellectual, and aesthetic interests. What is the role of the critic in that complex?

I have been semi-retired for a number of years and not so in touch as I used to be, with no office to ensure the flow of information. The critic is a public intellectual, and the public wants stories of fantasy, what I call the “Van Gogh syndrome” … cutting edge, innovative, breaking boundaries, etc. The academic journals are to display erudite knowledge, usually sugarcoated in the jargon of critical theory. Previously there was some space between these two extremes; now it’s hollowed out. It’s part of the decline of American culture and the rush to dumb it down.

The mantra of the NAE was “without fear or favor.” Will you explain the impetus behind that?

The mantra appeared in the first editorial written in October 1974. We then believed, as I believe now, that artists are “de-professionalized,” and the failure of the art education system is to blame. The market, academia, and museums are a highly complex arrangement, as indeed are Wall Street, Congress, the CIA, etc.

Insiders know of this. It’s a privilege more open in New York than outside of New York. We believed, and I still do, that the whole context of the artist, not just the aesthetic response, has to be considered. There is a great little book called Critical Mess by Robert Rosenblum, which has a series of essays that respond to that problem. There is much dissatisfaction with the American media and art criticism in particular. For instance, the New Art Examiner was under James Elkins’ nose when he wrote that excellent tome What Happened to Art Criticism, so I find it difficult to agree entirely with its premise. He included Jerry Saltz, a very popular lightweight, while Donald Kuspit from New York recognized that the NAE had made an important contribution to American criticism. I have to assume it was the usual inhibition of Chicago political correctness that inhibited Elkins from any professional acknowledgement [of the NAE] This and many other issues will have to be dealt with in the history of the NAE, if it’s ever written. I repeat what Winston Churchill wrote, “History is written by the winners.”