Yoshitomo Nara: Drawings 1984–2013

Yoshitomo Nara‘s art has consistently remained an international crowd favorite over the course of his decades-long career possibly because it is “not at all hard to understand,” as Masue Kato asserts in an essay in the recently published Yoshitomo Nara: Drawings 1984–2013 (Blum & Poe, $50). Much of the Japanese artist’s work has been described as figurative and a little humorous, if not imbibed with a subtle melancholy that lurks just beneath the surface of his ever-growing array of childlike subjects.

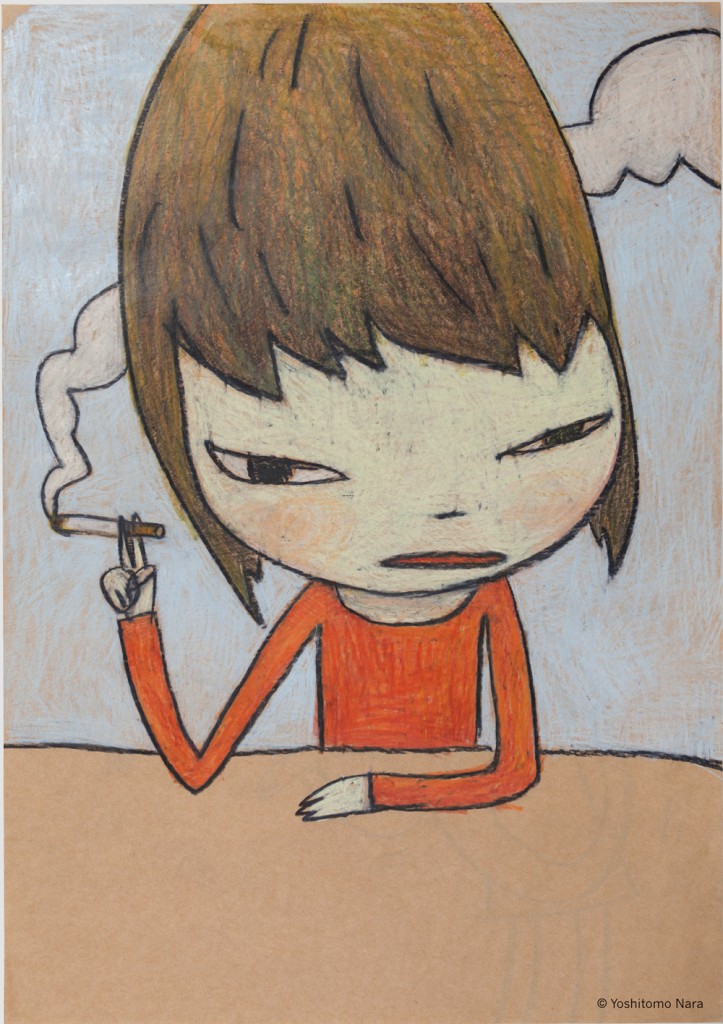

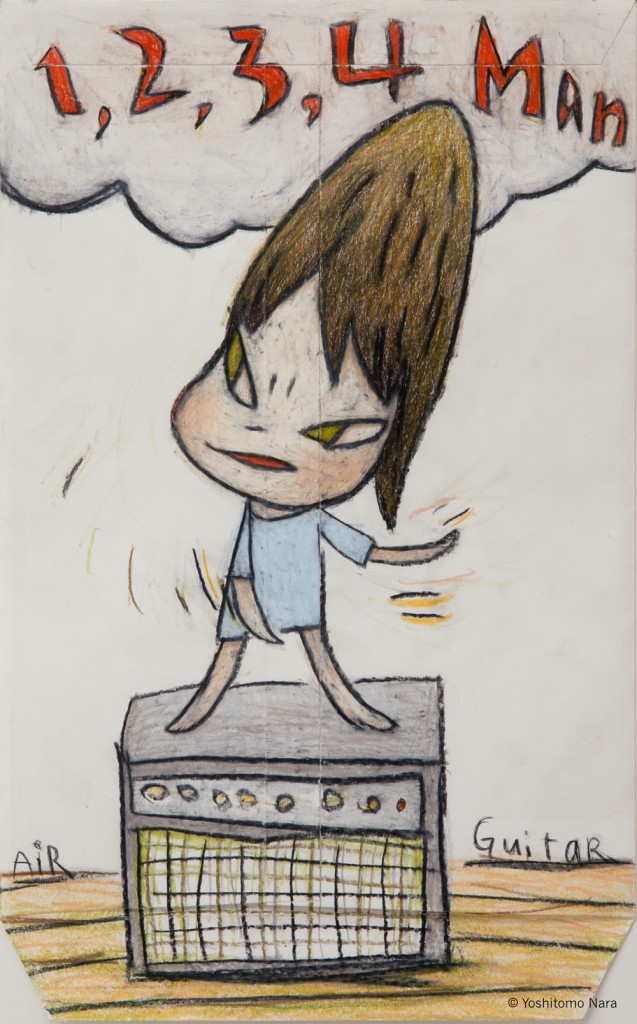

Nara has also proven to be a very personal artist for a large number of fans, many of whom are young and female. For my undergraduate thesis in cultural anthropology, I examined his fan communities in Japan and the Western U.S. and was amazed at the highly emotional responses that I received during interviews with self-proclaimed “Nara Girls.” I first encountered his work around age 15, in a bookstore in Tokyo that had a small display of his then-steadily growing number of catalogues. I poured through them all and settled on a collection of his drawings and diary entries. In addition to the blatantly personal, archival quality of those drawings and the clear intention given to the floating, often pop-culture referencing text surrounding his subjects, Nara’s work struck me because it was (and still very much is) unabashedly raw, but not overly loud. His characters reflect the smoldering anger of adolescence; his children, animals and children dressed as animals hint at the intent of violence but are bound by their helplessness, instead turning to props – costumes, musical instruments, flowers, cigarettes – to perform other kinds of subversive behavior. Many are dreamily meditative, while others seem simply unsure of where they are.

Nara’s drawings, at least to me, never really felt on any kind of “lesser” level of commitment than his paintings, sculptures, ceramics or photography, and as evidenced through his numerous exhibitions and how he continues to display his work, he seems to agree. Yoshitomo Nara: Drawings 1984–2013, published in conjunction with a major spring 2014 show at Blum & Poe in Los Angeles, offers a comprehensive overview of not only how Nara’s drawing style has progressed over nearly thirty years, but how interwoven his drawing practice is to his entire body of work. The artist’s sketchbook usually offers an unfiltered view into process that is unrestricted by protocols or project restraints, but as the book confirms, drawing, for Nara, is akin to breathing.

Kato’s essay goes far beyond simply outlining Nara’s history of drawing and employs both formal analysis and primary sources, including some of Nara’s diary entries. It is quickly noted that, because of Nara’s accessibility, his work has been interpreted in a number of ways. In the 1980s it was for its sociological and psychological undertones, in the 1990s and 2000s it was discussed as part of the Superflat trend in contemporary Japanese art, and more recently, in terms of his public projects in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake, it has been questioned in terms of the artist’s role in the community. Kato acknowledges that much of the talk around Nara’s style has fallen into an association with anime and manga subcultures, but refuses to accept that surface observation and dives into a thoughtful, spot-on tracing of his trademark image of the young, angry girl through explanations rooted in 19th century European methods for drawing faces and facial expressions, grid theory and Neo-expressionist painting. Overall, the discussion here provides palatable and essential critical context to better understanding Nara’s prolific output in his portrayal of human figures, showing that there is much more to his drawings than simple pop culture appropriation and punk lyrics.

Several of the works reproduced in the book have never been publicly exhibited nor included in previous catalogues; all highlight Nara’s penchant for drawing as a form of documentation when he is both in and out of the studio. The range across three decades includes tidbits of notable points in his career, from lonely, otherworldly studies made during his time studying in Germany in the 1980s to more recent incarnations of girls yelling into microphones. Overall, the tome is a beautifully-produced look at the previously under-examined lynchpin of Nara’s practice, sure to make fans fall even harder for his quiet blend of anarchy and dreaming.