Saving Chicago’s Only Holography Collection

“The building haunted my thoughts,” said Moshe Tamssot of his recent endeavors to restore the collection at Chicago’s Museum of Holography, which closed in 2009. On Dec. 4, Tamssot will host the “Museum of Holography Rescue Exhibit & disORDer Session,” with the goal of finding them a new exhibition space. The event will display selected holograms from the collection and feature a talk from Ed Wesly, a past employee of the museum. It will take place in a storefront a short walk away from the museum itself.

Tamssot started MakeItFor.Us, “a service that gets anything made.” The HoloRescue Mission is one the company’s projects, and the mission is unfunded. “We love to take on impossible projects and bring them to life,” he said of the efforts to restore the museum’s collection. The building will be sold again in the near future, and “[the current owner’s] plans are to sell [the collection] off piecemeal, and scrap the rest,” said Tamssot. “As a last ditch effort to save the collection, we’ve asked if we could put on an exhibit of holograms.”

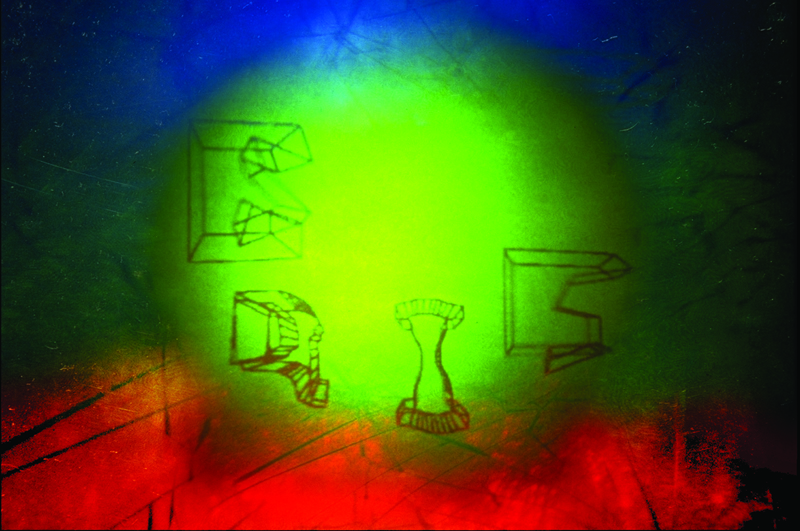

Holograms – at their most simplistic definition – are three-dimensional images that result from the interference of light beams. They are often referenced in science fiction, such as Princess Leia’s hologram from Star Wars in 1977, which is “the world’s most iconic hologram,” said Tamssot.

The technique was discovered in 1940 as a tool for scientific recording, and artists were quick to get on board, fascinated by its process and complexity. But holography’s progression in both fields was short-lived. “Now, most of our holographic experiences are limited to holograms that are used to foil counterfeiting,” said Tamssot, referring to credit cards and branded merchandise. “[Which is] another reason why the collection should be saved. There are many applications yet to be discovered.”

Opened in 1974 by Loren and Bob Billings, the museum is an emblem of Chicago and was once a huge attraction. Now, the holograms sit in the basement of the building, much less important to the current owner than they were to the Billings. Even more tragic is the story behind the museum’s closure.

The Billings were both prominent figures in Chicago, with Bob working as a sports writer for the Chicago Tribune and Loren’s involvement in science – especially holography. She began taking classes at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the 1970s, which led to the museum’s opening.

“If someone dedicates themselves to amassing the world’s largest collection of holograms, as Loren Billings did, then there was a reason and purpose for it,” said Tamssot. She and Bob ran it until Bob’s death, and, with age, it became difficult for her to run it herself.

Loren Billings became acquainted with people who claimed to be developing cutting-edge holographic filming equipment. They convinced her to take out a one-million-dollar loan to invest in their company, and she obliged, unfit to make such financial decisions. After warning Billings of potential fraud, the bank approved the loan with her insistence. The case became popular when Alexi Giannoulias, who approved the loan, became treasurer of Illinois. Billing’s son has since begun handling the debt.

The scam forced Billings to lose the museum and the collection. “While I enjoyed the holograms while they were on exhibit, it was Loren Billings’ story that really got to me. It felt like yet another incarnation of what locals call ‘the Chicago way,’ where the politicians and banks steamroll the common man,” said Tamssot.

The lack of attempts to revive the collection is a tragedy in and of itself. Holography’s history is in danger of being forgotten. Its importance in the evolution of art, science, and technology is often overlooked given its recent absence. Exhibiting holograms may be the only way to remind us of their place in time: “Once sold, who knows if any of these pieces will ever be publicly displayed again,” said Tamssot.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has the only standalone holography museum in the world. Most other museums closed in the 90s. Chicago saw a privileged longevity in its holography museum and place as a hub for holographic production – SAIC’s holography lab was around until it flooded and was never restored.

“Chicago celebrities ranging from Mike Royko to Michael Jordan had holograms of themselves made for display (Royko’s will be displayed on Dec. 4). Chicago was the epicenter of holography for a while, when it mattered. [The Billings] were pushing the bounds of technology in their time,” said Tamssot.

Since then, holography has seemingly lost its value as a medium. The equipment necessary to shoot holograms is expensive and difficult to use. It requires an in-depth understanding of the properties of light and a great deal of patience, which most see as tedious, but the artists drawn to it were fascinated by its process and the meaning behind it.

Holography’s ambiguous place in the history of art, science and technology is the very reason its relics must be kept alive and accessible. Tamssot hopes his efforts will prolong the life of Chicago’s holographic collection, one of the most extensive in the world. In an ideal situation, he’d like to see the collection adopted by an institution like the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art or the Art Institute of Chicago, but he is by no means limited to those options.

“We knew going into this that it was a long shot, but it’s in my nature to try the impossible,” said Tamssot. “Perhaps someone out there knows an individual, corporation, or public institution that’s committed to keeping the collection intact, and on public display in Chicago.” Tamssot hopes to find answers at the rescue exhibit.

“Beyond the holograms, I believe the true value of this experience is in the story of Loren Billings. … Hers is a story that deserves a happier ending,” he said.