The Barbican’s Digital Revolution is flashy, innovative, and tedious

The Barbican Center’s Digital Revolution exemplifies the most frustrating aspects of a life fully infiltrated by technology. Distraction reigns as flashing projections of video games and CGI films, along with incessantly alternating clips of digitally produced music, compete with the games and programs available on the computers dispersed throughout the venue.

The exhibition begins with a Speak and Spell, a Pac-Man game, and some examples of early personal computers and digital music interfaces. Headphones hung on didactics allow visitors to listen to popular songs created by the music interfaces. Stacked behind glass within industrially-styled archive shelves is the first computer for music, the Atari ST (1985), the Fairlight CMI 1979 synth, and the Linn LM-1 drum machine (1980). Other early works in this “Digital Archaeology” section of the exhibit allowed visitors to interact, like Lorna (1979), an interactive laserdisc choose-your-own-adventure story by artist Lynn Hershmann that takes place in a hotel. Lorna can be told to eat, take a bath, or make a call, all the while dealing with the anxieties of living. A set of pre-filmed scenarios are then played out based on the option chosen and Lorna enacts the resulting emotions, such as “fear of aging.” The arrangement of fine art, popular culture, and technological advances was less like insightful juxtaposition and more like cramming. The shelf beyond Lorna held a computer loaded with a copy of The Project (1991), the first Internet browser for the World Wide Web created for CERN-based scientists by Tim Berners-Lee and Robert Cailliau. Next to this were large screens depicting pivotal moments in the development of CGI: clips from Terminator 2 (1991), The Lawnmower Man (1992), Jurassic Park (1993), and The Matrix (1999).

The vague sense of chronological progression was frequently disrupted by anachronistic throwbacks, leaving the viewer to wonder what the curatorial narrative might be.

Opposite the CGI section were early digital drawing tools, the hardware interface Quantel Paintbox (1981), and early examples of algorithmic drawing games, such as Mutator (1990), which was created by William Latham and Stephen Todd and slightly mutated images with each click of a button. This amusing section also included an early online marketing campaign for Burger King: Subservient Chicken (2004) by Crispin Porter, Bogusky, and the Parbarian Group displayed a video of a man dressed in a chicken suit who the player could direct, to fly, rollover, kick, and so on, all through typed instructions. Form Art (1997) by Alexei Shulgin was less amusing, consisting of faces made out of the visual boxes that make up database forms. Sodaconstructor (2008), a java-based program by Ed Burton and Soda Creative, allowed users to adjust aspects of speed, friction, stiffness, and gravity to make kinesthetically accurate creatures that obeyed the laws of physics in different worlds.

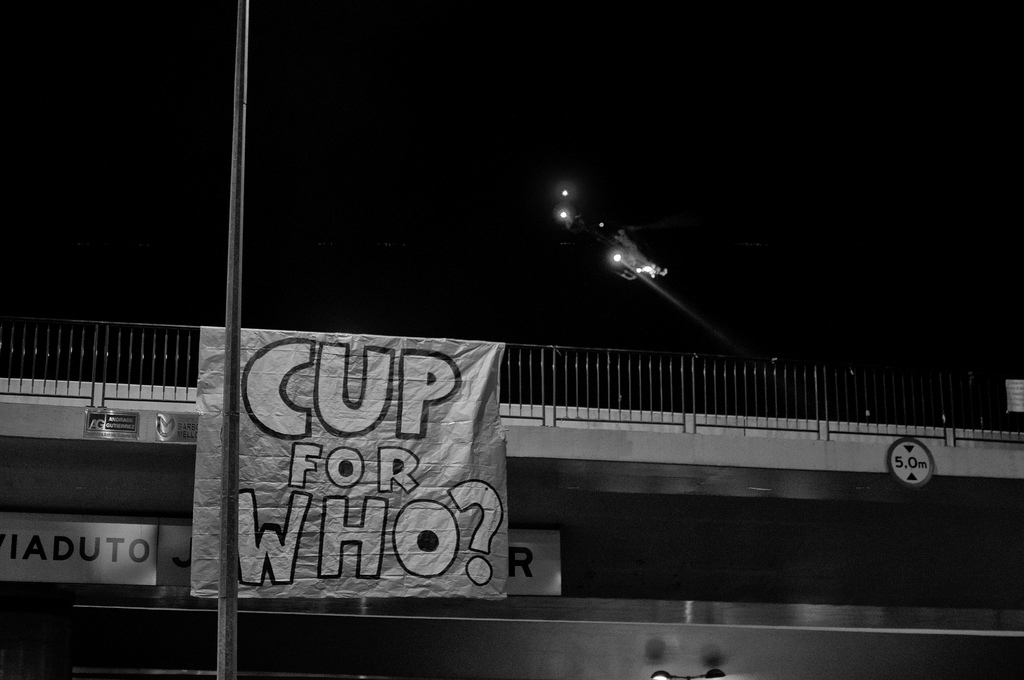

More programmed art was jammed into a corner next to the Minecraft (2009) station. We Feel Fine (2006) by Jonathan Harris and Sep Kanvar sources the phrase “I feel” from social networking sites, making a worldwide map of emotions; visitors could use the computer to focus on a particular location. Adam Ben Dror and Shansan Zhou’s Pinokio (2012) was a physical model of the Pixar logo, a lamp that followed faces with its light-bulb gaze. Escape III (2204), a clunky sculpture of birds made out of mobile phones, perched on a branch and tweeted when rung through using an old rotary phone. The Deleted City (2012) by Richard Vijgen mapped data salvaged from deleted Geocities community web forums. Another mapping project, James Bridle’s Dronestagram (2012) displayed a familiar Instagram-like consumer format of images of military drones.

Amongst these data-filled works, some more successful from others, I watched the same father who had shooed his fascinated son away from Lawnmower Man attempt to pry him from the addictive lure of Minecraft. A number of bleary-eyed children stood locked in a scene reminiscent of Cronnenberg’s eXistenZ, the game feeding off their young life-energy. Luckily, an interactive model of the 3D effects world of the film Inception (2010) immediately followed to catch the attention of children at a loose end. Bjork’s Biophilia app for the iPad was lodged into another tiny corner right before exiting into the next section of the exhibit. Passing through a curtain, singer and producer will.i.am’s face, projection mapped into a concave hole and wearing an ancient Egyptian crown, followed people with its gaze as shiny automaton instruments in glass octahedrons played along to his relentless pop singing.

The following rooms were some of the least crowded of the whole exhibition. A series of Kinect-centric installations re-projected users within painterly worlds or as animated creatures with smoke coming out of their eyes. I heard one visitor describe this area as “selfie-central.” The most interesting work here was Chris Milk’s The Treachery of Sanctuary (2012). Inspired by the caves of Lascaux, users were projected shadowlike onto the wall opposite. A flock of birds first landed on them, and then ate their shadows piece by piece. The last screen allowed the user to flap their arms and fly their shadow to the top of the room.

In the final space of this floor of the exhibition, Devart had commissioned a number of artists to create original works. Karsten Schmidt’s Code Factory (2014), an open-source 3D printer would live print works that had been chosen from an open call submitted online. Zach Lieberman’s Play the World (2014) hooked up Internet radio stations from around the world to the keys of a midi-piano.

Outside, there was yet more: an independently-designed games area and a row of random works that included interactive fashion, and an art piece about drones by John Cale. At this point I was exhausted and overwhelmed. The crowds, despite the timed entry, meant that much of the work in the exhibition was left unexamined. I dragged myself down to the Pit, the final part of the show, to experience an immersive interactive installation, Assemblance (2014) by The Umbrellium arts collective. A line formed in a dark hallway. We could see through a window into the space we were about to enter: a smoke-filled room where green, red, and blue lasers projected shiny rainbow shapes onto the floor. Light could be dragged and thrown by hand gestures. The participants all looked like acid-causalities in the limbo of a late-90s rave.

The digital sculptures and screens scattered through the halls of the early 1980s Brutalist building seemed more satisfying than the works within the overcrowded exhibition halls, mostly because there was both physical and mental space to consider them. Also they were free to view and did not require cueing for 45 minutes and paying £12.50 ($25). Despite containing groundbreaking technologies, artworks, and cinema, Digital Revolution creates a meaningless void, a flat plane of innovations. Either less works or more space — and well-placed benches — would have allowed for consideration instead of tedium.