Discourse as a Spectator Sport

Since arriving at SAIC, I’ve become aware of “discourse” as a very corporeal entity that I seem to haphazardly bump into every day, like that stranger that you just happen to see daily on the train, at Target or in the gym but never say “hello” to. Sometimes I even feel as if I get smooshed up against discourse in the elevator and then things just get awkward. Let’s call it Discourse with a capital “D”; I think it warrants the denotation of a proper noun if I’m going to imbue it with a sense of physical volume.

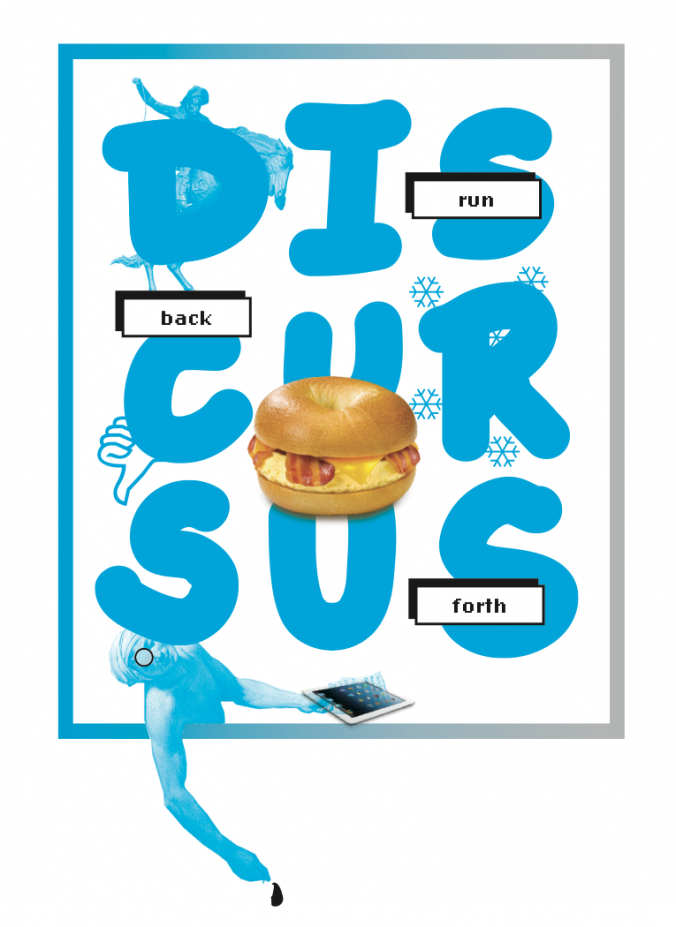

In seeking to understand the known stranger of Discourse, it helps to familiarize oneself with its Latin root, discursus, which means “to run back and forth.” This makes much sense, for just as it is difficult to shoot a moving target, so too is it to pin down a word that has rapid motion at the heart of its meaning. How, then, does one engage with Discourse when it’s always on the move? You just have to start running with it.

Just a few short weeks ago in late February, there was a Discourse track meet that went by the name of the College Art Association Annual Conference (CAA). If ever the act of running to and fro could be epitomized by something other than a person physically running to and fro, I believe that CAA did it. There was such a flurry of activity that it was hard not to start moving faster. The sheer number of people, breadth of ideas and volume of talking at any given event was enough to leave you as breathless as if you actually had gone for an uphill jog.

I attended a session entitled “The Present Prospects of Social Art History,” in which SAIC’s own Margaret MacNamidhe, professor of art history, presented her recent paper on Picasso’s Boy Leading a Horse. Four other art historians presented along with her; I’d like to say I was familiar with the others’ scholarship, but of course I was lucky to have just heard the names of one or two of them. This was simply because I haven’t been running this Discourse race for long, which brings me to my first point: Discourse is a marathon ran individually but completed collectively. As a graduate student in art history, I’m fresh off the starting block and possibly running too eagerly. I’m probably going to cramp up and vomit off to the side at some point while more seasoned runners breeze on by. But training with veteran marathoners is the surest way to improve and find one’s own stride, which is why I’m in graduate school in the first place.

The more seasoned racers are, of course, those who have been working in the field longer and have ample practice under their belts. But sometimes even practice can’t make perfect. UCLA professor Hector Reyes presented a fascinating study of the historical trajectory of medieval funerary effigies and their relation to David’s Death of Marat. However, that’s about as much as I can tell you — he read at such warp speed that I’m happy I gleaned that much from his presentation. As the first up to the podium, was it anxiety that made him speak so quickly? Or the bullish idea that he shouldn’t have to cut any research from his conference paper in order to fit it into the predetermined 15-minute time limit? Regardless of the cause, Reyes hurried presentation makes clear my second point: when it comes to Discourse, even experienced runners have off races.

The following presenter, Elizabeth Mansfield of the National Humanities Center, ran a great race. She offered a historiography of Social Art history that was spot on, explaining that it has had three distinct phases: positivist, critical and existential. The positivist model was prevalent in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and was tied into imperialistic modes of identification. The critical phase arose with Marx and featured a relocation of identity to class/gender/race, etc. As of the mid-twentieth century, Mansfield suggested that we had entered an existential phase of Social Art history, which focuses on where the social intersects with individual consciousness.

While I’m sure many may agree or disagree with Mansfield’s classification system to varying degrees, I do believe that she did something great in Discourse — she conveyed her thoughts in a succinct and relatable manner. In fact, all subsequent presenters in the session linked their work back to at least one of her “phases.” MacNamidhe very aptly identified her argument that Picasso’s depiction of a boy’s rein-less guiding of a steed in Boy Leading a Horse was a phenomenological study of gesture, and thus a manifestation of existential Social Art history. Alan Wallach of the College William and Mary (and undoubtedly the Bruce Jenner of this particular race), was happy to announce himself as a stalwart member of the critical phase.

Of course, this brings me to my third point: Discourse is as much of a relay as it is a marathon. Whatever our level of experience as racers, it’s necessary to keep the baton moving if any of us want to reach the finish line. With her easily definable phraseology, reductive as it may be in some ways, Mansfield offered a baton that MacNamidhe and Wallach had the wherewithal to run with both meaningfully and gracefully.

The final presentation of the session on the importance of form in social art history was given by Joshua Shannon of the University of Maryland. While his argument that Social Art historians should not shun formal analysis was provocative, his behavior was more so. Shannon unabashedly enjoyed his breakfast sandwich through the first two presentations, regardless of the chewiness of the bagel or the timbre of the crumpling paper wrapping. He also declined to present his paper at the podium as his forerunners did, and instead remained seated to make it more “conversational,” according to him. I can’t say that Shannon’s presentation wasn’t engaging, although I’d wager he thinks he’s a little more radical than he truly is. I simply found him a bit bizarre.

Which brings me to my fourth and final point about Discourse: sometimes you just have to run your own race.