For a while now, there’s been a societal consensus that video games are a waste of time. The term itself bears negative connotations, hence sayings like “Don’t play games with me”, or “He’s a player.” Parts of that opinion are justifiable; if you’re writing an essay on whether or not the characters in Hills Like White Elephants are talking about abortion, you might want to avoid a round of Tetris. However, as a ubiquitous and constantly-evolving medium, it’s important to note that video games should no longer be dismissed as childish play.

They might not be on the same artistic status as literature or film, but it’s evident that they are – slowly – approaching a level of storytelling that rivals those mediums. And although storytelling is a seemingly small aspect to emphasize, especially in relation to the technological implications of video games, its importance cannot be understated. Humans are storytelling creatures, a condition reflected in the insistence of modern video games to include narratives as the primary drive for completing a game. Most of the time, video games abuse stories, transforming them into tools to propel the player forward and consequently rendering them shallow and ineffective. But we’re no longer stuck with mustachioed plumbers who never seem to keep their princesses safe, or a small boy traveling with monsters to win badges. Instead, we have video games like Naughty Dog’s critically-acclaimed The Last of Us, games that passionately deny the notion of compelling narratives being incapable of existing within the medium. The Last of Us announces, to gamers and non-gamers alike, that video games are capable of more than entertainment. Like any creative medium, that makes it an important subject.

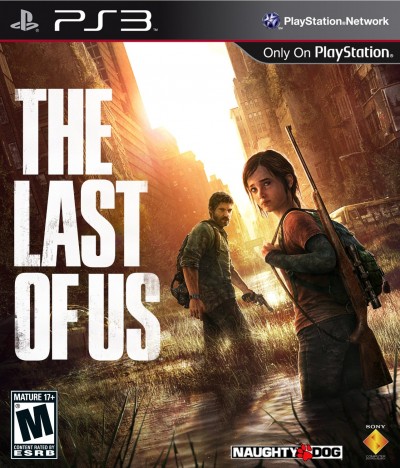

The Last of Us puts players in the shoes of Joel, a father hardened by a fatal virus that has plagued the country for over two decades. Soon after the prologue, the player is introduced to Ellie, a fourteen year old girl with a naivety matched by her bravery. The goal is to travel across America together and reach the Fireflies, an underground resistance group looking for a cure. As a zombie story, the game suffers from certain clichés – people die, others live, and surprise surprise, Ellie is immune – but they are offset by well-developed characters and a beautifully-realized post-apocalyptic America, which culminates into one of the most powerful stories to ever have graced modern gaming. In Extra Lives: Why Video Games Matter, critic Tom Bissell notes that games have given him “experiences. Not surrogate experiences, but actual experiences, many of which are as important to me as any real memories.” Such a statement can be made of The Last of Us.

But one of the hallmarks of a great story is its ability to tackle subjects that don’t directly relate to the story itself. For example, there’s a widespread idea that video games desensitize players to violence. Naughty Dog is aware of that; it’s an issue brought up with their Uncharted series, in which the main character kills hundreds of people during the course of the game only to still be labeled a “hero.” However, these lines blur in The Last of Us. Joel is less of a hero than he is a survivor. Strangle a hunter and you’ll feel your own grip tighten on the controller; bash one’s head in with a brick and you’ll wince. You can feel the life squeeze out of every enemy. The pixels have substance. The game’s visceral nature is especially important in the final sequence, in which the game forces the player, as Joel, to kill a surgeon. “You animal!”, another doctor cries.

That scene actually upset many players, who disagreed with the idea that they were required to murder an innocent in order to complete the game. The social implications of that decision should not be ignored, but it brings to mind a topic unique to video games: the player’s ability to control and affect the storyline. Often times he can; games like Mass Effect allow the player that kind of agency. But The Last of Us exemplifies that players are not characters in the game — they only enable them. In doing so, not only does The Last of Us comment on violence, morality, and heroism, but it also subverts some of the most common and relied-upon trends in gaming: the protagonist as the good guy, the player as the subject of the story, and the ending as a happy one.

Within three weeks of its release, The Last of Us sold over 3.4 million copies. That’s 3.4 million Joels and Ellies trekking through America; 3.4 million Joels murdering 3.4 million surgeons; 3.4 million actual experiences, not surrogate experiences. It’s not that The Last of Us opened the door to these things, but it’s exemplified the potential for video games to transcend the immaturity it’s so frequently associated with. I spent seventeen hours with that game (not counting the two more times I played through it), and they were as cathartic and self-revealing as most of the literature I’ve read. So the next time you boot up a PC or a console and feel guilty; the next time you spend hours in front of a screen and realize your day is gone; the next time you reach a “the end” screen with your mind scrambling and your mouth open, remember the time when you finished Harry Potter or when the credits ran on The Breakfast Club, and congratulate yourself on hours well-spent.