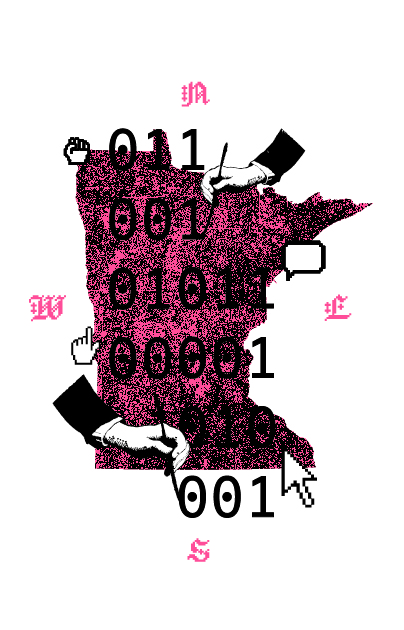

Vestigial layers of analog cartography bleed into digital-age mapping

The ground is purposefully sloped, not by any forces of nature, but by recent upheaval and reset. There is a new field, elevated above the foundations of old, new layers to the previous, new use. Walking across the newly paved cul-de-sac, I move beyond its edge and sink into the old land. There are two discernible stripes emanating from the knoll, indicating years of traffic, now permanently halted and redirected. The asphalt above has long forgotten its gravel ancestor beneath. Wild growth reclaims the old road, growing lush between the two stripes, and outside of them as well. The tire-wide lines, still with their rocky, permeable surface partially inhibit growth, appearing like a stereo version of Richard Long’s performative transits across various fields and slopes in Peru. The surface has a memory.

The memory is located in Rochester Township, not far from the red dotted lines of city limits for Rochester, Minnesota, a small city seventy miles south of Minneapolis. The vacant and rough pathway I traipse upon what was once part of a small route that crossed the south fork of the Zumbro River, a tributary of the Mississippi. Twenty-five years ago, a new road was built from the east, cutting through the field and hills and eventually making contact with the existing circuit and its two farms. In favor of the new roadway, the bridge over the Zumbro River was taken out, and much of the route through the woods abandoned.

I begin to walk the stripes, selecting one side as I do. I admire their scarce detectability like apparitions and wonder how much longer they will be visible. Tangible histories in the landscape are often things of finitude, objects that signify within the landscape gradually become disassociated from their narratives, faltering and impartial stories. The ground is evaporating, being overlooked, turning to translucent, dubious signs and surfaces, and much, much less. Ghosts are here.

For many years, maps drawn since the route’s change showed the street, known as Old Valley Road, as something that still crossed the Zumbro River. Other maps showed the new road leading from the other direction, called Meadow Crossing Road, and extending to the river’s edge. Until last year, many online maps such as Google and Bing showed the road in this way, terminating at the former bridge site. It had been many years since any cars could drive that far down the road.

Among the many means available to see this process, land changes are clearly made visible through the maps we have available to us, in both print and digital form. There are editions regularly published, yet rendered out-of-date due to the constantly evolving landscape of roads and highways. It is important to note that both types of media are subject to the same errors and speed of updating. Yet today we rely on digital data, which can be updated and made available to people much more easily than print.

Aside from its accompanying visual metabolism, the raw data of digital cartography (e.g., place-naming) is soft. It is subject to change with the whims and exploitations of the user of the land. More than anything, the text in any map is a system predicated upon recognition and significance. The way in which we identify a place changes over time. For example, all mail now requires an address number and zip plus four. Gone are the days of using a last name and county road, town, and state, to mail something to a rural address. Gone too are the days of using an intersection as an address to mail to an urban location. Online ordering is where this change is more visible as many address entry systems for online order forms will “correct” your address by implementing abbreviations. In other cases, the name of your town, city, or populated place may be disregarded by location databases if a larger, more significant place is nearby. The very text of the system is being altered over time, a combination of functional efficiency and trends of the general populace.