Stefan Sagmeister’s “The Happy Show” makes us smile

Graphic designer Stefan Sagmeister’s “The Happy Show,” at the Cultural Center through September 23, is a sweet-humored investigation of a muddled question: what does it mean to be — and how can one achieve — happiness?

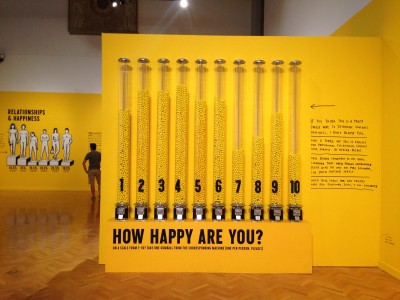

Sagmeister poses this question free of alternatives, and it is no fun bothering (yet) to tease out the negative — “why be happy?” or, “how to be not happy?” — when your tour guide is, himself, happy. No melancholic mind could have conjured the sun-colored walls and ergonomic and interactive forms of the show; a joy-powered bicycle, lit push-buttons that deposit firm aphoristic suggestions (“Do ten push-ups. Now.”), and a row of ten sky-high gumball machines (also yellow) that encourage visitors to record their level of happiness by extracting a (free! yellow!) gumball from the appropriate canister. Levels eight and ten were the most popular, with seven close behind. I chose level five (mostly because it was the least empty) and the security guard chose level one in a surreptitious stroll-by. Despite the miasma of strong health and charming idiosyncrasy, charisma and carefully calibrated playfulness, I fell right into Sagmeister’s work. I was invited to dine on hip infographics, and this wholesome food tasted good.

Thus, there is no weight to a critical assessment of the concept itself. Of course, anything is prey to a disemboweling critique. It all remains as tacit as the concept of happiness itself: take it apart, and this vibrancy crumbles. Doubtless Sagmeister realizes this: rather than treating the concept (or the feeling) of happiness as some ineffable mote of being, or as a transcendence of emotional strife, he takes happiness in a fully assumed form. It can be measurable, it can be explicable, and it can be investigated.

Though his work posits various influences on well-being (marital status, goal-setting, environment, community), there are glorious lapses in the logic. A piece of wall text, for instance, comments that the accompanying statistics show how married people are ‘happier’ — but then continues with a caveat: perhaps happier people are just more likely to wed, rendering the statistics (which are already specious) entirely null. (Happiness folds back into enigma.) In another place, Sagmeister speculates on the distinction between art and design: “To do something without any goal and without any function has its own beauty: the difference between a walk in the park and a commute. It’s the difference between art and design.” Sagmeister himself is straddling these definitions, approaching a “useless” project with a utilitarian bias. Art and design, if we wish to adhere with Sagmeister’s distinction, are pitted against each other here; their communicative functions are pushed to articulate an idea that is at once too presumptuous to be artful and too abstract to be designed. Yet, Sagmeister’s project circumvents the discursive terrain of emotion by being precisely that: presumptuous. Happiness-as-concept is predicated on belief: a universal set of faiths that allow for its existence. Happiness-as-emotion is no less numinous.

Sagmeister’s initial question — how can I be happy (or happier)?) — gives way to another question (what does it mean to be happy?), which gives way to a final question, its negative reflex: how am I not happy? Because happiness is given the luster of transcendence (in the show and in our everyday lives), the valor of a “high level” or the result of hard work and wise decisions, we grant it positive value. We dwell in it’s converse (un-happiness), and likewise, allow melancholy, malaise or depression a similarly seductive value. The sense that our lives run linearly, that we can move through junctures that will eventually ricochet us into happiness (or drag ourselves ‘up’ from sadness), is heartily (if unwittingly) embraced. And even when we are able to regard happiness as a continually fleeing state, it is with a sense of irony: ‘that’s life’.

Contemporary art too shies further and further away from subjective or quixotic concepts, such as emotional states. The growing trend for art to be useful or applicable, quotidian and democratic, seems to presuppose the elimination of these things. (My argument would be that ecstasy need not be transcendental.) While many people will still accept a concept like ‘happiness’ wholesale, there seems to be little space left for work that rests on a metaphysical framework, based on the conceptual credo of refuting “assumptions.” When left alone, wafty or romantic concepts are certainly in danger of accomplishing nothing: when we leave “happiness” alone, the artistic project cannot extend beyond itself, and “happiness” can only be explored as a representation of “happiness” rather than a subversion, alteration, or stuttering of a commonly held belief.

“The Happy Show” manages to keep the assumption intact while taking on another set of representations — a “good,” pleasing design to lull the senses. Sagmeister’s perception of art (opposed to design) is that it is goalless and functionless, and from a designer’s perspective, this may be true. The dichotomy he envisions is, however, a false one (art does just as much as design does), and it is here, in the “difference” between design and art, that “The Happy Show” fails — becomes too snug in its definitions. But it’s too late: we’ve already climbed aboard. Sagmeister’s work assumes happiness. And although it doesn’t carve out new territories of thought, there is an undeniable delight in being enclosed by those yellow walls, if only for an hour.