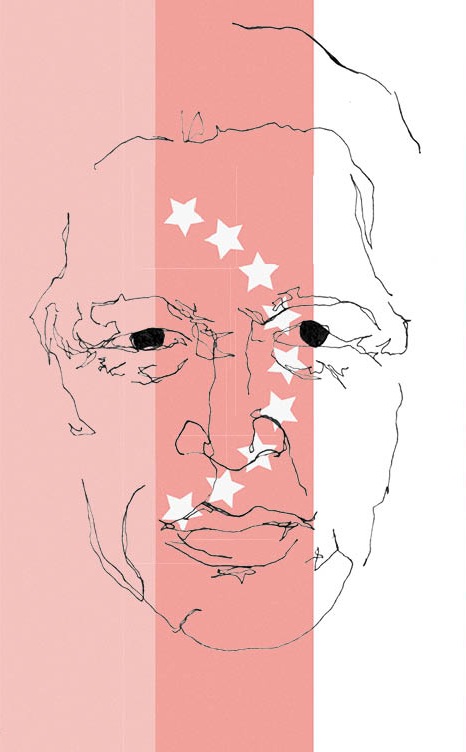

In 2009, filmmaker Oliver Stone released a documentary titled “South of the Border.” In the 78-minute long film, Stone set out to debunk the U.S. media image of then-president of Venezuela Hugo Chávez perpetuated by U.S. media — that of a mindless dictator, a 21st century Fidel Castro. Stone had it easy; it’s not difficult to find laughable footage from Fox News or CNN pundits. He then embarked on a trip around Latin America, to hang out with Chávez and the rest of the leftist heads of state of the region to clarify, through first-hand conversations with each one of them, just what is going on south of the border.

The film attempts to bring to the forefront that the shift to the left in countries like Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina and Brazil is in reaction to years of destructive U.S. meddling in Latin American affairs — through the International Monetary Fund, forceful removal of leftist leaders in CIA-backed plots, etc. — and former Latin American leaders who would easily comply with White House orders. It’s the brown and the poor people in an armed but peaceful revolution, Chávez says to Stone, against white oligarchies.

Stone wasn’t trying to be neutral. Throughout the documentary he is as much of a protagonist as Chávez and the rest of the leaders. He sits next to them and always appears on camera, nodding his head in agreement with their leadership and congratulating them on their success. Throughout the documentary Stone features outside interviewees who can speak in favor of what is referred to as the Bolivarian Revolution. Nevertheless, Stone himself acknowledged to reporters covering the release of the film that the production was not “dealing with a big picture, and we don’t stop to go into a lot of the criticism and details of each country.” He said, “It’s a 101 introduction to a situation in South America that most Americans and Europeans don’t know about.”

Today, Stone can look at the more liberal media for forgiving assessments of Chávez. Outlets like Al Jazeera and Democracy Now were quick to offer more levelheaded opinions after the death of the Venezuelan leader in early March. Both outlets attempted to break down the reasons why Chávez was such a beloved political figure in the first place. The millions of mourners who took to the streets of Venezuela should have made it clear to outside viewers that Chávez was much more than just a charismatic president bribing his way into the hearts of his people.

Mark Weisbrot, columnist and co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research, has been leading the charge recently with hard economic facts that support how the situation in Venezuela has improved considerably, especially for those living in extreme poverty. Al Jazeera and Democracy Now have summoned Weisbrot when in need of a clarification of just how positive Chávez was for the country. There has been a 50% reduction in poverty and a 70% reduction in extreme poverty, Weisbrot cites in his appearances on both outlets. Plus, living standards have increased for most residents of the country, especially thanks to the availability of universal health care. Chávez is never recognized for these successes in the U.S. media, in order to portray “a one-sided, negative picture of the country, and of course of Chavez himself,” Weisbrot recently wrote.

Weisbrot has had recent on-screen confrontations with Rory Carroll, The Guardian’s former Latin American correspondent who was based in Venezuela for six years and recently published a book on Chávez titled “Comandante.” What Carroll offers is mostly on-the-ground evidence from his time living there — the hospitals available to access this universal health care touted by Weisbrot are not in good shape, and the “misiones” (missions) set up to help aren’t that efficient either; the nonexistent separation between party and government leaders and the easy access to TV and radio waves gave Chavista leader Nicolás Maduro an unfair advantage in the recent election; and Caracas is now considered one of the most dangerous cities in the world. Carroll and Weisbrot have been pitted against each other on both Democracy Now and Al Jazeera. When Carroll was invited to comment on NPR about the recent election results, Weisbrot was quick to come to the defense of Chávez with a piece on Al Jazeera titled “Haters Gonna Hate,” and cited the hard numbers and statistics he now probably knows by heart.

It’s fair that outlets like Democracy Now and Al Jazeera choose people like Weisbrot to comment on Chávez — facts are good. But what is the value of more levelheaded media outlets, if they fall into the same trap: calling upon a talking head to come to the defense of one man and his politics. And what is it important to focus on, really — the people living in the country or the reputation of a leader? If we can learn one thing from history, it’s that no one man (or woman, in the case of Argentina) has the key to all of a country’s problems, and we should be wary of all of them.

Instead of looking to the president, why not cast a wider net and look closer at the situation on the ground? Venezuela’s leadership would be rightly served with more information about thriving social movements like feminists, gay and lesbian rights organizations, economic justice activists, and environmental coalitions that were given a voice by the Chávez administration, a rare occurrence in Latin American countries still very much plagued by misogyny and homophobia. Can we put a face to this oft-cited mass of Venezuelans who have benefitted from universal health care and literacy programs? What about the leaders of the neighborhood councils that make sure that the Venezuelans living in dire poverty get more access to the services they deserve? It is telling that the opposition leader Henrique Capriles has promised to maintain many of Chávez’s social programs. Yet the reasons for their success are shrouded in talking heads babble, disputing whether or not the polarizing leader did well.

The consequences of setting up a government so dependent on the image and reputation of one leader are clear now that Chávez is dead. Maduro ran a campaign that capitalized on his close relationship with the late leader, going so far as to say that Chávez had appeared to him in the form of a bird.And now the close outcome of the election and the inability of leaders on both sides to tone down their rhetoric and put a halt to their acts of defiance has left people no choice but to fight it out on the streets, in the name of each candidate. The people are desperate for solutions to serious problems of crime, shortages, violence and corruption.

In many ways, Chávez, and the presidents from the region that followed his lead, embodies the fantasies of a bred-in-the-bone leftist: he’s a socialist leader from an oil-rich South American country constantly giving the middle finger to the U.S. But in attempting to inform, commentators in global media — left, right and center — should look beyond the polarizing personality of a leader and focus more on what the policies enacted mean for the people. The late Argentine president Nestor Kirchner said it best to Oliver Stone. “In a multilateral world, you can’t have just one power decide for everyone. It’s bad for power itself,” Kirchner commented. “This is something I always tell Hugo – I’m very close with Chávez, he’s a friend — but I tell him: you need to build collectively, you need to have 10 presidential candidates. It can’t just be you. Otherwise, if you get sick and you die, the whole process will be over. To believe that one person can give the guarantee is like believing that only one country can resolve all the world’s problems.”