My discussion with Cara Krebs (MFA candidate in Fiber and Material Studies 2013) began with a touch of American kitsch: we talked about cheeseburgers. Their form. Their allure. Their status as objects of shame. I reminisced about being a young kid and seeing the gummy candies shaped like cheeseburgers, and how I never brought myself to bite into one. Coincidentally, cheeseburgers were a common denominator between Cara and me. Cara reached into her bag and pulled out a cloth wallet she bought that is shaped like a cheeseburger. It was a soft, round, trompe l’oeil object that folds open like two buns, one side with lettuce and tomato, and the other with a realistically rendered meat patty. Both the cheeseburger gummy and wallet fall under what Cara calls “novelty,” a category that is part of a larger system that structures her practice. Held by magnets on her studio cabinet, there is a Venn diagram she created that graphically organizes her interests in food into categories such as: fudge-like, translucence, novelty and color. For her, the wallet presents a desire to make a food-shaped “completely functioning and necessary object that can be really cute, uncanny and weird.” These material forms that generate a purely indulgent desire are what interests Cara Krebs — channeling the materially luscious, attractive yet edible.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Cara and gain insight into her latest homage to an American classic: a giant, out of this world, grilled cheese sandwich. One can imagine that this piece will garner a lot of attention in the upcoming MFA show. In reference to her subject matter and overwhelming scale, I heard a visitor on Open Studios Night last fall pass around the name Claes Oldenburg. But this sandwich and her practice is not part of that conversation. There is no kitsch, or overt irony. Cara experiments with material, plays with different modes of rendering artificiality and fantasy and assures that a viewer is humbled by an intimate experience.

As the artist describes it, an “otherworldly” space exists in between two eight-foot-long slices of Styrofoam bread she has built. The top slice of bread has a type of oculus at its center, a hole over which she has placed a green sheet of Plexiglas. It filters the light into the piece. A curved concave canvas structure supports the slices, painted with rich green tones, textures and shapes that give a pleasantly alluring sense of depth as it comes into contact with the green light from above. This dimensionality is questioned when sculptural elements are hung from the top slices of bread: stuffed yellow fabric oozing down and gesturing toward stalactites of dripping cheese. On the floor of the interior are organic constructions — barnacle-like mountainous structures of sphagnum moss, and buttery clumps dripping out of the artwork. It is a fantastical world that cannot be fully contained within the bread.

Krebs creates “a new kind of permanence” for the grilled cheese sandwich, part of her interest in using the material qualities of foods to create immersive environments. The lowbrow, yet celebrated cultural status of the grilled cheese sandwich provides a platform for Krebs to visually abstract it as a comfort food. “Eating a grilled cheese is a simple, humble, but completely indulgent experience,” she told me. Her material construction’s portability and relation to children’s food allows it to become a type of toy, where the food has “grown so large that it becomes weird.” While this tremendous scale is a first for Cara, she says: “I’ve always been interested in other worlds.Things that I just found intriguing, joyful, or important. Creating worlds for them to exist in and to be notable. Maybe it comes from a compulsion for collecting things. I’m interested when [worlds] come together in the context of art, which is made for viewing and experience.”

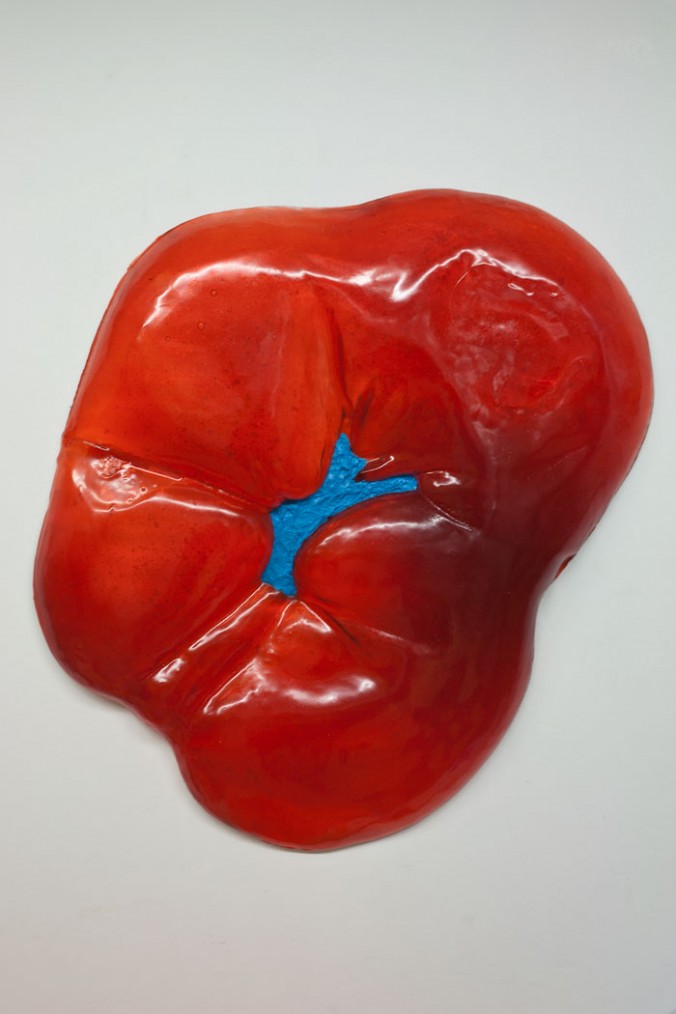

Hanging on the wall next to the sandwich is a red, smooth and amorphous sculptural object with a blue center. Light bounces inside of its rounded surface. Almost like jello, it has a seductive yet subtle, playful quality. Krebs informs me that it’s made of the same material as gummy worms. Its squishy and fluid shape translates with a type of organic plasticity that beckons the viewer to touch it, or act on it. This is the suspension Krebs aims to provoke, a desire to pass through the object.

Her interest in “translucence,” also part of her diagram, derives from the visual access that this squishy solid gives the viewer. “You can pass through it,” she says. The liminal space blurs the boundaries between desire, indulgence and fantasy. Similar to the grilled cheese, the piece creates an intimate space of an imagined tactility, of inhabiting the material landscape.

In one of her previous works, Krebs took shortening and petroleum jelly and mixed the two. She spread a large quantity of the mixture on her studio floor, paying close attention to creating a whipped texture with delicate peaks. She aptly titled it “Frosting.” The desire for these foods is channeled into a desire to exist with them in the same space. Moving from a work like “Frosting,” which acted more like ornament to the ever-growing grilled cheese, Cara Krebs exhibits a desire to create a space that is inviting, bizarre and safe. Foods that represent simple pleasure are also sites for transformation, doors to other realities and complex material explorations. But viewers of art are never given access into this world, but are rather asked to remain on the threshold imagining what it would be like to pass through it.