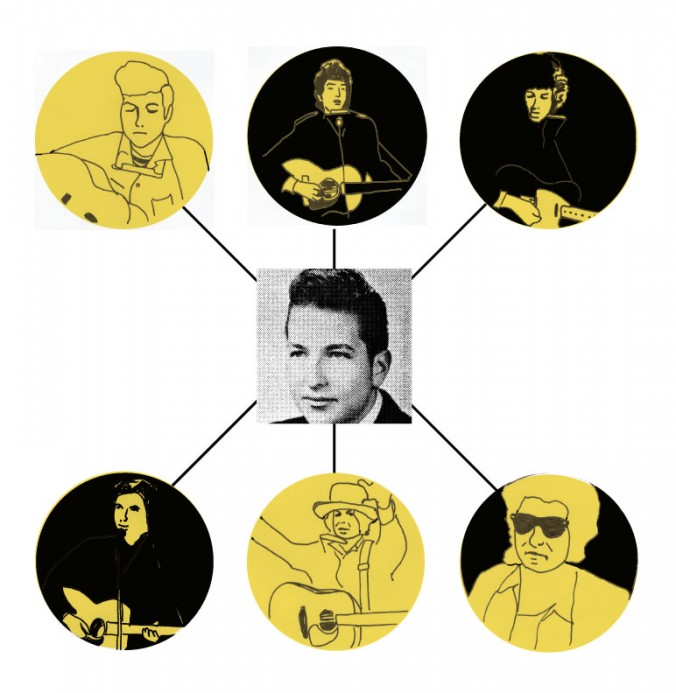

When it comes to appreciating the work of Bob Dylan one can, as Dylan himself has, choose a character to focus on. There’s the Dust Bowl-indebted rural protest singer, the speed-freak beat poet with a rock and roll band, the cowboy gypsy, the gospel preacher, and the ancient Delta bluesman with his deepest roots in minstrelsy. His ideas have been expressed in races, genders, words that are not his own and in mediums and genres outside of songwriting. It may be that the one fact we know about Dylan is that he hasn’t allowed himself to be put in any categorical boxes, and that the career of singer-songwriter, which he helped to invent is still being used by artists today.

Dylan has always had a remarkable sense of where and when to employ each version of himself and how to sound convincing when doing so. On his first album he name-dropped Woody Guthrie and covered blues standards. Guthrie and the blues greats were his heroes and he invoked them in his early material, but he knew when to drop the homage and play the right parts.

David Yaffe is author of a recently published collection of essays about Dylan’s unique sense of identity and relevance today titled “Bob Dylan: Like a Complete Unknown.” In it he writes: “Dylan’s time in the trenches of the civil rights movement coincided with a notable absence of the black musical influence he absorbed elsewhere, consciously or unconsciously, Dylan seemed to sense that this was not an occasion for musical blackface.” In conversation with F Newsmagazine, Yaffe elaborated on the point, “Dylan’s engagement with race is so unique. It was so special, and I think it told you so much about racial appropriation in American music and culture. Much of Dylan’s career is based on having a persona that includes this element. It’s partially imitating black music, but it’s partially his own intonations. He’s not going to pretend that he’s not who he is.”

Dylan made the most clear statement about himself during an 18-month stretch of the mid-1960s. “Bringing it All Back Home “ (1965), “Highway 61 Revisited” (1965), and “Blonde on Blonde” (1966) give listeners a true sense of the artist at his most original and unaffected. All of his influences from Odetta to Rimbaud are in these records, but filtered through Dylan’s mind and delivered with his own voice. “If you think about the way he sings ‘Love Minus Zero/ No Limit’ he doesn’t sound like a Woody Guthrie imitator and he doesn’t sound like somebody that’s imitating the blues,” Yaffe said, “He’s almost singing the way he talks.”

“Like a Rolling Stone,” from “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands” from “Blonde on Blonde” are prime examples of Dylan leaving folk, blues, and protest behind to deliver something personal and groundbreaking.

To fully arrive at his newfound artistic freedom, Dylan had to betray the following he had cultivated during his years of finger-pointing protest songs and character development. When he went electric at the Newport Folk Festival in 1965, he alienated his dedicated fan base at a time when he had them hanging on his every word. His 1966 electric tour with the Hawks was met with intense booing from fans in England, but he was giving them what Yaffe calls “some of the most powerful rock and roll ever recorded.” Then when he had the opportunity to embrace and elevate his countercultural icon status in the late-60s he instead retreated to Woodstock, New York, to record a country album and did not tour again until 1974. These seemingly career-killing moves allowed him to stay ahead of his audiences by avoiding a typecast situation that would keep him a folk singer, a rock and roller, or the voice of any movement.

After returning in ‘74 Dylan went back into role playing mode, unsatisfied or disinterested in being the rock and roll poet forever. “Desire” (1976) was an ornate collection of gypsy storytelling co-written by theater director Jacques Levy. The tour for that album was the circus-esque Rolling Thunder Revue — a travelling show with wild costuming meant to distance Dylan from his painfully vulnerable divorce album “Blood on the Tracks” (1975). He made yet another dramatic change in the late 70s by publicly converting from Judaism to Christianity and releasing the albums “Slow Train Coming” (1979) and “Saved” (1980). After a creative lull in the 1980s, Dylan returned in the 1990s as a character hybrid of the grizzled bluesman he once aspired to be, and the natural aging process that has left his voice ravaged.

I asked Yaffe why he thinks Dylan has remained a pervasive cultural force at 71 years old, having released his best-loved and most influential work in the 1960s: “He invented this job, and the job is singer-songwriter. He was aspiring to something beyond his own time,” he said. “He was aspiring to wisdom at a very early age and that was something that wasn’t true of the early rock and roll. So even though pop music has gone through so many manifestations, I feel like the model that Bob Dylan set in motion, and is still doing on “Tempest” (2012), is still a model that’s being used.”