A chain-link fence made of cut-out reflective sticker is pasted on one of the windows and glass door of Yollocalli’s gallery, facing Blue Island street. Its creator, Phill Cabeen, one of Yollocalli’s teaching artists, carefully cut out most of the negative diamond spaces of the fence. Visitors and passers-by can see themselves on the thin reflective lines adhered to the windows, but can still look past the negative spaces into the gallery. Yet, moving towards the glass door there are less cutouts and, therefore, less information about what’s inside. Once standing before the door, all they can see is their own reflection.

Yollocalli Arts Reach is a youth initiative of the National Museum of Mexican Art. It was established in 1997 as an arts education and career-training program in Pilsen. It coordinates formal and informal educational programs including free classes, satellite classes in public schools, exhibitions, visiting artists and residence programs, time arts events, performances, video screenings and workshops. Cabeen has been a teaching artist at Yollocalli for a couple of years. The institution provides a great social and cultural service for the Pilsen community, offering a free, safe and creative environment for local young artists. It aims to keep them away from gang violence, a big problem in the neighborhood, while contributing to the rich artistic exchange Pilsen is known for.

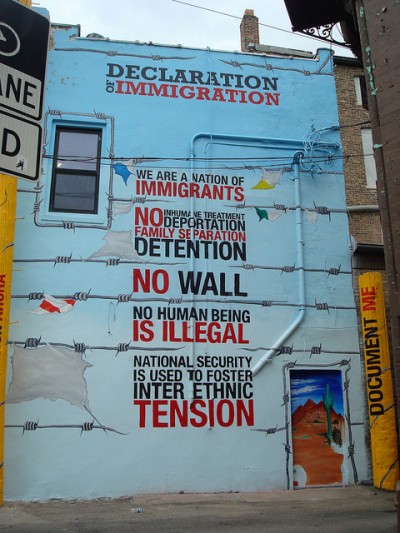

A fence is a loaded symbol, “Especially in this neighborhood,” observes Cabeen about his piece in the gallery. The tall, slender, long blonde-haired artist was born in Washington D.C, though raised in Chicago’s suburbs. He has lived in Pilsen on and off, since 1997. His wife is a German immigrant whom he married after they met in China and lived in Germany for two years.

“We’ve had our own story with migration, so, to some extent, it is autobiographical, but as an artist I am more interested in what a border or a fence means for us on a more abstract level. That imagery pushes a lot of buttons,” he explains. “What happens when that fence we have so many associations with is starting to reflect us, up to the point where we are looking within ourselves?”

His mother is a fiber artist and her sister a dancer and choreographer, so art has always been a natural thing to do in his family. He attended University of Illinois Chicago as an undergrad, initially in the photography and film program, but after a couple of years he switched to art history.

After he graduated, he lived in China for four years, where, as mentioned before, he met his wife. When they came back to Chicago in 2003, six years after he left, he began working as an English teacher to pay the bills. Thanks to this temporary job he discovered he wanted to teach art, and got a masters degree in Art Education at Columbia College. “I wanted to work with kids who were unhappy with the way art is being taught in their schools.” He recalled being very frustrated when his high school art classes where only about learning skills, instead of teaching or encouraging the exploration of deeper processes for art production. As an art educator, he wanted to change that, and he chose to do it in Pilsen.

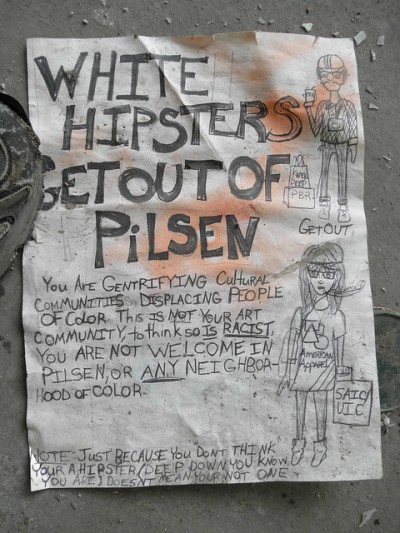

But six years later, a lot had changed in the neighborhood. Gentrification had begun transforming the community and it took him awhile to figure out the changes. “Initially, I lived in Carpenter, and the gentrification has been moving, for the most part, from the East to the West, so in 1997 there was an art strip along Halsted, but it wasn’t yet translating into condo development, or new hip restaurants, bars and shops,” he recalls. “The people on the street still represented pretty much only the Mexican-American community with everything it implies, including the gang leaders hanging out in the corners.” Years later, when he came back to Chicago, he considered living again in that side of the neighborhood, but he did not find it appealing, or affordable anymore. “It had already become a little too self consciously hip, and I know I am a total hypocrite because I am part of that initial wave of white people who made the neighborhood seem attractive to other hipsters.” Every once in a while the Latino people on the street give him a hard time. “Sometimes they spit on the sidewalk when I walk by or yell something like, ‘go back to Wrigleyville where you belong,’ but I just try not to get caught up on that.

In terms of its location, Pilsen is a good place to live. Housing is affordable, it is everything but a food desert, and it is close to downtown. For an artist like Cabeen, the neighborhood is interesting way beyond its convenience. “There are a lot of people here that are interested in art and politics, so you have the opportunity to get into conversations with people to whom it really means something. Here it is not just chitchat, these are people who are fighting for their families rights, or participating in serious activism to affect changes in migration laws for their community.”

As a white American, Cabeen is an outsider in this struggle, but he is still interested in the neighborhood politics. “That is a way in which I feel very at home, on the one hand, because I share a lot of those views on immigration and labor rights, and I am definitely on the left end on that spectrum.” Nevertheless, he wishes the community’s awareness of social borders were more global. “The border between the U.S and Mexico is not the only national border. I feel a little bit frustrated with the specificity that the community here looks at those issues. I’ve met a lot of other Latino artists and activists who transcend this vision, and it is perhaps because they are not Mexican-American.”

“In those matters Yollocalli is quite exceptional because the kids who go there understand that they can be themselves, no matter what that means, and that is part of what makes it an attractive and safe space,” explains Cabeen.

As the neighborhood continues to change, he still feels comfortable in his apartment, but admits not knowing how long will it be before he decides to move out, or will simply have to because of the rising housing prices in the area. He fears as well that the political engagement he finds so interesting about the neighborhood will be watered down with the arrival of more white and wealthier people. “Unfortunately, along with the hipsters often comes less political engagement, because the political concerns that unite Pilsen definitely feel far more abstract to my peers from the suburbs.”

When asked if he has noticed Mexican families moving out of Pilsen for this reason he answers, “Not per se, but it’s easy to notice a dramatic shift in the population walking on the streets. You see more young people from all ethnicities, including more Latino hipsters, as well as a lot more African Americans than I have ever seen before.”

When the income level of a neighborhood rises, so do the job opportunities. Artists find in this aspect, the major benefit of gentrification, although it usually does not last long. Cabeen agrees, but hopes the process brings a longer lasting exchange of ideas, “it is interesting because the more hipsters arrive, the more businesses want murals or street-art-looking stuff outside their buildings. I hope that this will have some effect in terms of building more bridges between the Pilsen community and the rest of the city, because people are coming from other neighborhoods and making connections here.”

Gang violence has played a key role in making the gentrification process slower. Perceived as a dangerous neighborhood, it will take some years for people to stop being scared of spending time or moving into Pilsen. Cabeen remembers a project in which his students from Yollocalli interviewed people about violence in the neighborhood, and he recalls being really surprised when he listened to one of the interviewees responding, “Well, of course I wish there was less violence, but the gangs do keep the yuppies out, so, honestly, I’d keep the situation just like it is.”

When asked if he has witnessed violence caused by this gentrification process, he says, “No, it is only among gangs. This last spring was really bad in terms of violence, so I was glad to be part of keeping some kids away from it.” Yollocalli does play an important role in this matter, being a healthy space that attracts teenagers and young adults toward art and out of criminal activities, but Cabeen is skeptical in terms of how fundamental the role of Yollocalli is in shaping these young people’s lives. “A space like this might help some kids to stay out of trouble, but pretty much only the kids who had already chosen not to be a part of it. What it does is it gives them a safe place to hang out where no one puts any pressure on them about it. It does help to keep youth engaged in something else, but I don’t think it is a magic bullet either.” There is a great need for more outside intervention to get kids out of gangs, and although they do help, it is not a problem that art communities focus on, or are capable of solving.

The National Museum of Mexican Art announced last year that it is struggling to find the budget to keep the building which hosts Yollocalli and Radio Arte, a free broadcast journalism training program and radio station. The big old building is right at the heart of Pilsen, in the corner of 18th street and Blue Island and considering the important role these education programs have played for over a decade among the community, this will represent a serious loss for the gentrifying Pilsen and a step further in detriment of the rich and valuable Latin culture that has been developing for years in the neighborhood.

Carlos A. Cortez, Chicano labor artist and poet said once at the opening of the 21st century,” Don’t forget, ART (in the hands of the bosses) IS THE VANGUARD of REAL ESTATE!”