New exhibition at the MCA shows diverse aspects of Post-black artist

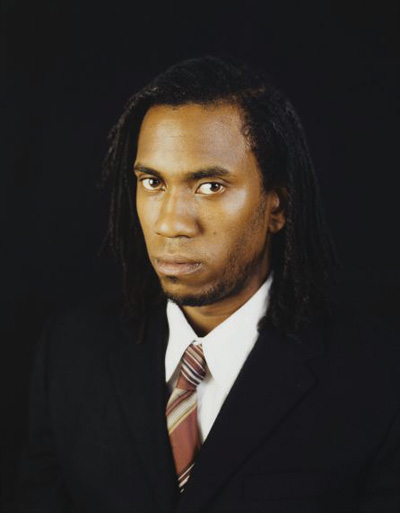

Photo courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art.

Ancient astronomers turned their eyes to the sky and shaped meaning by plotting the chaos of distant points of light. This act of creation served a dual purpose. It facilitated the placement of a mythology firmly within a historical tradition (i.e. creation myths) and also creates a system of augury through which one can predict what will come, as in zodiac horoscopes.

The term “post-black” refers to African-American artists who seek to create new identities within a historical narrative and codify their precedents. In this there is a shared impulse with the ancient astronomers who reached points of reference and drew original connections between them. Artists like Rashid Johnson (who has unflinchingly borne the assignation “post-black” since curator Thelma Golden termed his work as such in 2001) have constructed “Cradles of Purpose” by appropriating the iconography of crypto-Muslim sects, prominent artistic and historical figures and the wild cosmology of the Afro-Futurists.

At the heart of Rashid Johnson’s body of work is a deeply ingrained sense of humor and play. Even when addressing topics as serious as black identity, it can be difficult to gauge whether he is mocking or seriously undertaking this task of historical re-configuration. Johnson recently opened his first major solo exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Chicago. He worked closely with curator Julie Rodrigues Widholm to select a body of work, which includes photographs, video installations and “shelf-like” installations produced over his 14-year career.

The video “Sweet, Sweet Runner” (2010) calls to mind the classic 1970s film “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” and welcomes visitors to Johnson’s exhibition. The protagonist of the original film was a young African-American on the run from white authority figures. In Johnson’s re-telling, the protagonist appears to be on a casual jog through the streets of New York. Johnson also scores his film to a ’70s funk soundtrack that simultaneously draws a parallel to the source work while also creating a heightened sense of drama, lampooning the plight of the contemporary black man.

This funky soundtrack and Johnson’s use of mirrored surfaces help create a carnivalesque atmosphere that carries the viewer throughout the exhibition galleries. Johnson’s mirrors also perform another function by addressing a contemporary reading of the W. E. B. DuBois concept of “double consciousness.” Johnson titles one of his shelf-like pieces “Triple Consciousness” (2009) and uses three copies of Al Green’s “Greatest Hits” (1975) as a sort of tripartite mirroring. Thick black wax (a recurring element in his work) covers the surface and offers a backdrop for gold spray-paint that echoes a street art aesthetic. Compare this piece to its companion “The Shuttle” (2011). For this Johnson moves from the gritty, urban-voodoo altar construction and instead references the astrally-inclined cosmology of Afro-Futurists like Sun Ra. The shape and sleek mirrored surface invokes space travel while the prominent placement of a book titled “The Universe” leaves little leeway for interpretation.

“Men are born.

Kings are made.”

— Fela Kuti

Message to Our Folks”

Museum of

Contemporary

Art Chicago

Until August 5, 2012

mcachicago.org

Johnson flirts with navel-gazing in his aesthetic of incorporating everyday objects he calls “hijacking the domestic.” One gets the impression that the objects on Johnson’s shelves — and other recurring symbolic references, including the Public Enemy “crosshairs” — might have been too casually gathered from Johnson’s life.

The “shelf-like” pieces that seem to dominate the show, in both number and towering size, present more concerns than satisfying results. SAIC Art History Professor Delinda Collier noted that nostalgia and relying on history may be a flimsy premise — a towering house of cards that can’t withstand the slightest shift in breeze. Once an artist makes a game of reference it can be difficult to move away from it as analysis. One might end up searching for obvious connections that are not there.

Johnson’s work feels more at ease when he is playing with and subverting more aesthetic conventions. A highlight of the show for Collier is “Antibiotic” (2011). This oversized piece of black soap and wax is almost an anti-Pollock work. It operates like a black hole, seemingly sucking the color out of the room. Where Pollock lays colors, Johnson begins with a black surface and gouges out lines. Another striking piece is “Body Blow” (2012). The violent appearance of black paint that explodes out of the mirrored surface before dripping down is palpable in its sense of violation. The viewer is inextricably drawn into and situated in the context of the thick dark streak splitting the piece in two.

Perhaps the strength of the exhibition is Johnson’s photography. Artfully curated into a “salon chic” presentation, one has many options for engaging this body of work. Stand back and let the overwhelming presence and articulation of his work overwhelm you. Or stride forward and engage each work in turn. Johnson began his career as a photographer and his astute, sensitive eye is clear in each image selected.

There is no question of whether Johnson is a gifted artist or if he was ready for such a high-profile exhibition. He has produced a wildly diverse and creative body of work that is more than served within the framework of a retrospective. It is perhaps best to engage his work in such a manner, and see the points of light Johnson has selected (or created) in creating his artistic mythology. It is important not to get buried in the details illuminating Johnson’s personal cosmology and instead get lost in your own version of the starry-eyed reverie he invokes.