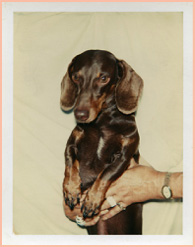

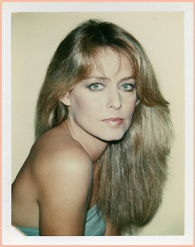

(Farrah Fawcett), 1979

(Uncle Same), 1981

gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts

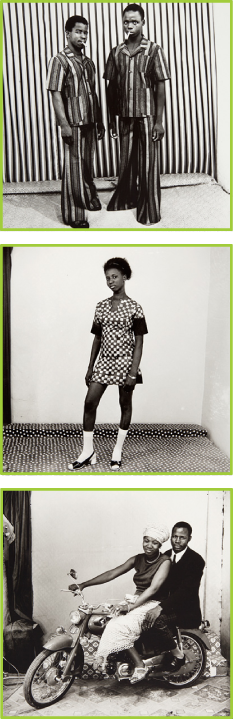

youth culture comprised, not of celebrities,

but regular, cool, young, Malians

diChroma photography

Andy Warhol is an undisputed icon of American art — his work merged high art and popular culture, highlighting connections between money, fame and cultural value. So, the current exhibition of Warhol Polaroid’s and silver gelatin prints at the DePaul Art Museum should easily be the most interesting part of the current show. However, the Studio Malick exhibition on the ground level of the museum is more compelling, not only because Malick’s photos lack Warhol’s overexposure. The two shows together create some interesting parallels, which was one of assistant curator Gregory Harris’ intentions for hanging the series simultaneously.

Studio Malick is a showcase of Malick Sidibé’s portraits taken in Mali after the country gained full independence from French colonization in 1960. The photos, both studio compositions and impromptu party photos, show an exuberant youth culture comprised, not of celebrities, but regular, cool, young Malians exploring recently embraced forms of entertainment and fashion. Sidibé was, in some ways, the forebearer of today’s bar-glamour photographers — spotlighting the impossible stardom of those of us whose 15 minutes of fame are less than likely, but who clean up pretty damn nicely on the weekends.

The exhibition is made up of Sidibé’s photos reprinted from his negatives as well as some of his original “chemise” — print folders that would have been displayed in his studio window and used as examples from which his subjects could pick what photos they wanted to purchase. The print folders add an air of authenticity and nostalgia to the show, offering a glimpse at Sidibé’s process as well as the initial commercial nature of his career. It wasn’t until an exhibition in Paris in 1995 that Sidibé’s photos gained international attention. He has since received the Hasselblad award for photography in 2003.

The images themselves range from energetic club shots to carefully composed studio images. One exemplary studio frame features a Malian couple seated on a motorcycle — the man with his shoes shined, donning a suit and tie, perched behind the woman in the driver’s seat wearing a string of pearls and a smirk.

The Andy Warhol photographs are on the second floor of the museum. Included are 25 Polaroids and silver gelatin prints ranging from images of Farrah Fawcett to a reluctant-looking dachshund, which may have been one of Warhol’s pets. The selections are a portion of a gift to the museum from the Andy Warhol Legacy Program and were chosen by Harris for their quality as well as to highlight the breadth of subjects in the full collection. The Legacy Program requests that their collections be displayed within a certain amount of time after being gifted, which was the museum’s other motivation for the current show. Despite the necessity of their display, they do offer an interesting parallel to Sidibé’s body of work in subject and tone.

Even [Warhol’s] dachshund

would rather be doing lines

of coke or getting a blow job.

In contrast Warhol’s images are intentionally artificial-looking. Most of the images were later used as references for paintings or prints and weren’t necessarily meant to stand as works in themselves. Many of the Polaroid subjects are wearing heavy makeup to eliminate shadow that would have impeded their later use for Warhol’s high-contrast final pieces.

Both series give an incidental nod toward the ability of photography to make icons out of its subjects. While some of Warhol’s subjects are anonymous, his handling washes them with an aura of untouchability — even the dachshund would rather be doing lines of coke or getting a blow job. Sidibé’s subjects, on the other hand, while still irresistibly cool, seem invested in the portrayal of their subculture.