Photographs by the author. Illustrations by F Newsmagazine.

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities, commonly known as the Egyptian Museum, has been at the center of the nation’s history since it was established in 1902. It has witnessed colonial rule, a king, a revolution, three presidents—and most recently, yet another revolution. Located right on Tahrir Square, a place that is now familiar around the world, the Egyptian Museum continues to occupy a dynamic role in the country’s unfolding history.

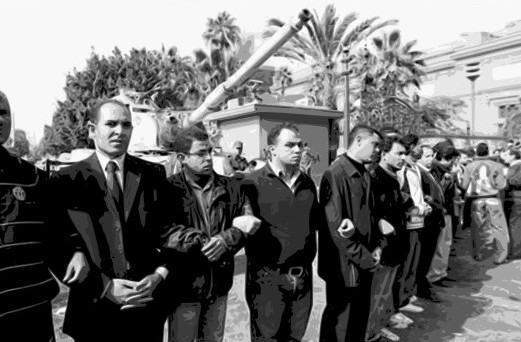

During the uprising in late January, the museum was broken into. In the period of a couple of minutes, Egyptians formed a human chain around its premises to protect it. This simple but symbolic act astounded people who were watching the event around the world.

Around January 30th, Zahi Hawass, the celebrated Egyptologist who was appointed Minister of Antiquities just a couple of days before Mubarak’s resignation, stood inside the museum to announce that nothing was stolen. But slowly, he started to change his story. On March 15th, he published a list with 54 missing objects on his blog and resigned the same day. He was reappointed to his post a couple of days later, to the surprise of many.

There has been a lot of commotion around the Egyptian Museum in the past couple of months, to say the least. I decided I needed to visit it once again, post-revolution.

The Egyptian Museum was built in 1900 by French architect Marcel Dougnon, and opened to the public in 1902. Its 107 halls hold the biggest collection of Pharaonic antiquities in the world. The structure represents Egypt’s colonial past; and its content, Egyptian history. There are about 120,000 objects in the collection, with some major highlights including the Gold Mask of King Tutankhamen. When bystanders banded together to protect the museum with their own bodies during the revolution, that act symbolized the a revival of the Egyptian people when confronted with a possible disintegration of their past.

One of the first things I noticed while entering the gardens of the museum is the burnt building on its left. That building was the National Democratic Party’s headquarters, a major symbol of corruption in Egypt. During the revolution, it was set on fire. I could see the scene from my rooftop while I was in Cairo in January, but I hadn’t been up close.

It was unbelievable to be standing right in front of it, and I couldn’t take in its proximity to the museum. The wall separating it from the museum is very low, but I had never realized it was right there. There is a small restaurant in the premises of the museum facing that building, but no one seemed taken aback. I guess people had had the time to get adjusted to everything.

My bag was checked three times before I could enter the museum, and photography isn’t allowed inside. When I tried to understand why, an officer told me that it is unacceptable that “we” think we can do whatever “we” want after the revolution, that there are rules we have to abide by and that Egypt isn’t chaos. I didn’t know who “we” were, probably young Egyptians; or maybe just Egyptians, period. I went all the way back to the main gate to place my camera in a safe. Thinking back, I don’t think I was ever able to take pictures in the museum, but the fact that the officer’s reaction was so aggressive seemed odd. The museum staff had a lot of adjusting to do after the revolution, especially that they were blamed for the lack of security, but this doesn’t justify his attitude.

The Egyptian Museum looked the same as I remembered. A beautiful, pink-orange colored structure with a grand entrance that is poorly maintained, but that holds magnificent statues, objects and artifacts. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the museum wasn’t full, but it wasn’t too empty, either. Courageous tourists take advantage of the good travel deals being offered to Egypt these days—attempts to lure tourist dollars (a mainstay of Egypt’s economy) back into the country.

There aren’t enough hours in a day to walk around the entire museum and see everything. I noticed, as usual, that the museum was inadequately preserved, and there wasn’t enough security. I saw people touching ancient columns and marble sarcophagi, and there isn’t a single alarm that went off.

I talked with a guard at the museum. He is an officer from the tourism police and claims that he’s been working at the museum for 16 years. He didn’t give me his name but was eager to talk to someone. The officer said that he had been inside the museum during the days of the revolution, and said that the police had been criticized for not protecting it enough. But, “How can we protect it when we are less than a hundred men facing thousands of people?” he protested.

He blamed most of the museum policies on Zahi Hawass, whom he nicknamed “El Zoz.” The misuse of funds, the lack of employee training … he pointed his finger at Hawass for anything and everything. He confirmed that most of the stolen objects were brought back to the museum, but it seemed like he thought there was some sort of insider job as well. He declined to elaborate.

I went on with my tour and was amazed by the quantity of objects we have. There are artifacts and statues everywhere, and no matter how many times I go to this museum, I keep discovering new pieces. The grandiosity of the different dynasties is indescribable. Moreover, what is inside of the museum is not everything we have. It is said that 90 percent of the objects are stored, due to a lack of space.

It was beautiful and moving to see citizens protecting institutions such as the Egyptian Museum and the Bibliotheca Alexandrina (the famous library of the city of Alexandria) during the violent days of the revolution. Even if most of the protestors had probably not visited these institutions before, they knew that they hold something worth protecting.

This event truly shows how cultural institutions play a vital role in any society and in any circumstances. They represent part of a nation’s history and often its future. Currently, 22 new museums are being built around Egypt, as part of the Ministry of Antiquities’ efforts “to build a better infrastructure for the future” (in the words of Hawass). Among the most important ones is the Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM). Once established, it is supposed to be the biggest national museum in the world. The competition to design the museum was won by an Irish firm, and several other international firms are working on the interpretation and exhibition design of the interior. It will be located two kilometers away from the famous Giza pyramids and will extend over 120 acres. The USD 500 million museum was originally scheduled to open in 2013, a date that has been pushed back to 2014—and now, after the revolution, 2015.

With the uncertainty that is reigning in the country, no one really knows how this museum will evolve. Moreover, it is located somewhat outside of Cairo and I wonder how accessible it will be to Egyptians. Next to the pyramids and away from Cairene traffic, it is an excellent location for tourists, but not necessarily for the people who live in Egypt. I can only hope that this museum, along with the 21 others, will keep the newfound patriotism of Egyptians alive.

In the same way a lot of things surprise me during my visit to Cairo this summer, a lot of great things have also arisen with the revolution. Today we feel that everything is in our hands. Despite the challenges that I described above, there is still a pervasive sense that it is possible to improve the state of the Egyptian Museum; it is possible to make Egyptians feel more connected to their past; and it is possible to make Egypt ours again. And there is no better way to start than with our very own cultural institutions.