By Ania Szremski

Shirin Neshat represents everything that Western curators love in contemporary Middle Eastern art: highly marketable tropes like veiled women, calligraphy-covered skin, and meditation on gender inequalities in Islamic society, all wrapped up in easily consumable media like photography and film.

Fortunately for the viewer, though, this Iranian-born, New York-based artist smartly evades the obvious approach to her subject matter. As the current screening of Neshat’s film “Rapture” (1999) at the Block Museum demonstrates, she instead exploits these now commonplace tropes in subtle, complicated ways. Neshat gracefully avoids the crude pitfalls art world darling Shadi Ghadirian so easily falls into, for instance, in her eye-roll-inducing “Like Everyday (Domestic Life),” a series of photographs depicting veiled women with various household objects replacing their faces. It’s a relief to find an artist capable of engaging gender issues in Islamic societies in a more fully-dimensional way.

“Rapture” is a two-channel video projection divided down gender lines. The male protagonists of the narrative are projected on the left wall of the gallery, the women on the right (Neshat exploited this binary technique in a series of films made in the late ’90s, like “Shadow Under the Web” of 1997, “Turbulent” of 1998 or “Soliloquy” of 1999). This binary formulation is stressed by the artist’s stark use of black and white (down to the actors’ clothes — women in black veils and robes, men in white shirts and black trousers). The viewer, meanwhile, is right in the middle, confronted with the constant dilemma of where to focus her attention; she can’t fully grasp the action in one scene without turning her back on the other.

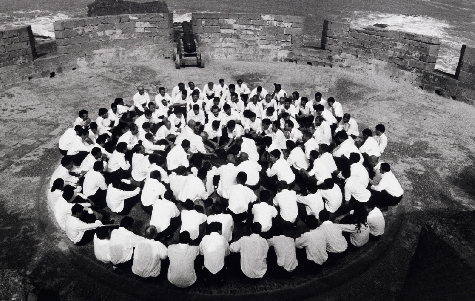

The film begins with absence: the world of the city is represented on the left (the men’s side), with a shot into an empty hallway in a seemingly abandoned Moroccan fortress, while on the right (the women’s side), we see limitless, craggy desert. Suddenly, the body makes its appearance: a crowd of men striding aggressively through the fortress, a line of veiled women quietly walking through the desert, until they stop and stare at each other across the gallery space.

From here, the actors take turns watching each other. The women stare in stony faced defiance as the men break out into a fight or wash themselves in preparation for prayer, while the men stare down at the women from their ramparts as they ululate, pray, and chant, offering up their palms covered with calligraphy, as if in protest.

Throughout, the male and female bodies organize themselves into gorgeous, dynamic patterns that swirl and sway across the screen, revealing Neshat’s background in photography. By the end of the piece, the men remain ensconced in their seaside fortress, watching and waving enthusiastically as a few women make their escape by setting to sea in a small boat.

Throughout, the male and female bodies organize themselves into gorgeous, dynamic patterns that swirl and sway across the screen, revealing Neshat’s background in photography. By the end of the piece, the men remain ensconced in their seaside fortress, watching and waving enthusiastically as a few women make their escape by setting to sea in a small boat.

The 11-minute projection is a compelling vision richly layered with sound, which is also bifurcated; the men move to a soundtrack of urgent chanting and pounding drums, while the women are mainly associated with the ethereal music of Iranian singer-composer Sussan Deyhim.

“Rapture” is thus at once a visual, auditory, and somatic experience. The viewer experiences the work not just by watching, but by actively listening and turning her head or body back and forth. This engagement of multiple senses suggests that Neshat’s almost obsessive doubling ends in the viewer’s experience. While the film itself is defined by seemingly countless dualities, like male/female, black/white, active/passive, urban/rural, confinement/escape, and noise/silence, the viewer is literally and metaphorically in between, not belonging to either scene, but caught in the nexus of opposing gazes.

This politics of spectatorship help to complicate a project which is profoundly engaging, but potentially problematic. On the one hand, Neshat’s work is indeed an express critique of problems she witnessed after the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran. But on the other hand, Western curators and critics can take that critique too far; “Islam is bad for women” has been the unfortunate subtext for some of the criticism on Neshat.

This issue of cultural representation is especially sticky for women artists from the Middle East. Other feminist artists from the region, like contemporary Palestinian performance artist Raeda Saadeh, have faced local criticism for unquestioningly adopting the terms of second-wave feminism, and depicting the subjugation of Muslim women in ways that implicitly support U.S. and European invasions of the Middle East in recent years (Gayatri Spivak’s old line about white men saving brown women from brown men).

Stakes are high for these artists, and the soft power politics of reading Arab feminism as a critique of Islam itself is manifest in Carolee Walker’s uninspired review of the execrable 2009 “[Dis]covering the Veil” show for www.america.gov, for instance. This is just one example of an uncritical reading of the trope of the veil as a “problem” for Muslim women in Western society.

Criticism of Neshat’s work has tread these dangerous waters in the past. But in the final analysis, at least for this reviewer, such critiques simply don’t live up to an installation like “Rapture,” in its sheer complexity, ambiguity and emotional force. Despite the artist’s “either/or” filmic techniques, “Rapture” can’t be reduced to any one ideological camp. It remains irresistably in the middle.