When artists are being censored not by their educators, but by their peers, has something gone awry in the educational system? Or is that merely the nature of the critical beast?

by Amanda Aldinger

School of the Art Institute Chicago (SAIC) student Anne Marie Lindquist knew that her newest installation piece — showcased in the Sullivan Galleries at SAIC’s recent Spring BFA show — would generate controversy. She just didn’t expect her most ardent critics to be her very own peers.

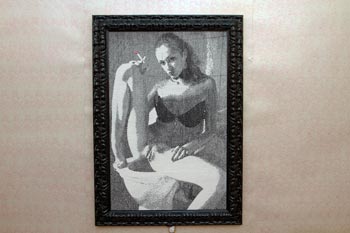

Consisting of weavings (created using a computerized jacquard loom) sourced from internet pornography, the installation is set in a simulated New York City living room. According to the artist’s website, the installation speaks to “privacy, appropriation, art culture, and the state of our social sexuality … an immersive environment that forces sex on the viewer, taking sex out of its private viewing context and placing it in an elevated space typically reserved for prided objects of beauty and worth.”

The image depicted on the front of Lindquist’s postcard, entitled “Picnic with Apples,” is an illustration of a woman clothed in a pink tunic, crouched on the ground and bent over a pile of apples, which she is gathering to put in a basket. The tunic is lifted to expose her buttocks and the woman’s positioning exposes her vagina and labia.

Although provocative and graphically sexual, Lindquist’s installation is technically sophisticated and encased within a framework of intellectual and critical means, placing her work far outside the realm of the gratuitous. So why would all of her marketing materials advertising the installation, posted and distributed throughout the School, be consistently removed and torn down from public view?

Lindquist realized what was happening to her postcards almost immediately after she began distributing them. She posted a pair of cards, one with the image showing and one with the show information showing, on each floor of the MacLean building and put stacks out where appropriate.

The next day, the stapled image cards were gone yet, “the text card was still there, but it was hanging awkwardly,” Lindquist explained in a recent interview with F Newsmagazine. Some entire stacks were also missing, and others had the top card flipped so that the image was facing down.

“To me, my postcard image has an ambiguous read, socially and figuratively,” Lindquist said. “Is she bending over or is she being bent over? It is a question that integrates my experience of being bent over with the overarching matter of whether or not a woman’s choice to bend over for a camera means she is still in control of her body.”

Lindquist was one of eight students given a special installation room at the BFA exhibition, meaning that her work had undergone extensive mentoring and critique from her professors throughout the duration of her process. So, when Lindquist keyed into the fact that her installation was being purposefully censored, she went directly to the administration and spoke with Felice Dublon, the Dean of Student Affairs.

“At first I thought it was from Student Life because I didn’t get the cards approved, but then I thought, ‘why are they leaving the text up; the information?'” Lindquist explained. “So I talked to Student Affairs and they checked it out and said that no one had been taking them down, that they don’t do that with student show cards ever — you don’t have to get those approved, apparently.”

“Student Life mentioned that there is a method of student censorship that just happens,” she continued. “If students just don’t like things they take it down. [Dublon] said that’s probably what was going on.” If someone had wanted Lindquist’s card, there were plenty available. “Who’s going to rip a stapled image card off to keep when there’s a stack of them right in front of you?” she asked.

SAIC is known for its contemporary and progressive educational practices, as well as for its mentoring and encouragement of advanced conceptual approaches to creating and exhibiting artwork.

This approach is supported in the curriculum description of the undergraduate school on SAIC’s website: “Students develop the ability to respond with sophistication to visual phenomena and learn to organize perceptions and conceptualizations both rationally and intuitively. Classes prepare students to be effective writers and speakers; to make coherent and unified oral presentations of material; to develop a thesis, idea, or argument in written form; and to handle concepts with greater sophistication.”

When discussing SAIC’s association with student-produced controversial art, it’s important to note that SAIC has a strong history of supporting artwork that has been contentious within the public sphere. Furthermore, these cases also illustrate that controversial imagery extends beyond the depiction of sexual acts or human nudity.

In 1988, SAIC was thrust in the middle of controversy when student David Nelson’s painting of Chicago’s late mayor Harold Washington, wearing only a bra, G-string, garter belt and stockings, was exhibited at SAIC.

Created in response to the deification of Washington after his death, the painting was impounded by police “after angry black aldermen removed it,” according to Ray Hanania and Tim Padgett’s May 1988 Chicago Tribune article, “Controversial painting reported damaged.”

The painting was returned to Nelson with a five-inch slash down the middle and a demand from Mayor Sawyer and 100 black ministers that Nelson apologize for painting the piece. However, SAIC, holding true to its policy of not censoring students, supported Nelson and refused to punish him for painting something simply because it contained controversial imagery.

“The faculty Senate is aware that many have been offended by the content of this painting. We support their rights to voice their concerns, yet we cannot condone censorship,” SAIC Professor Frank Barsotti stated at a press conference.

The following year, in 1989, Illinois legislature actually reduced grants awarded to SAIC from $130,000 to $1 as punishment for exhibiting student Scott Tyler’s “What Is the Proper Way to Display the U.S. Flag?” in which an American flag was placed on the floor, and viewers were invited to step on it and record in a book — difficult to get to without stepping on the flag — how they felt.

The following year, in 1989, Illinois legislature actually reduced grants awarded to SAIC from $130,000 to $1 as punishment for exhibiting student Scott Tyler’s “What Is the Proper Way to Display the U.S. Flag?” in which an American flag was placed on the floor, and viewers were invited to step on it and record in a book — difficult to get to without stepping on the flag — how they felt.

Despite resounding public backlash, SAIC allowed the piece to hang for an additional four weeks before it went on to travel to multiple exhibitions across the country. According to the June 1996 New York Times article “Art or Trash? Arizona Exhibit on American Flag Unleashes a Controversy,” journalist B. Drummond Ayres noted that, “Chicago officials maintained that the work constituted desecration of the flag, in violation of a local ordinance. But a judge ruled that ‘when the flag is displayed in a way to convey ideas, such display is protected’ by the Constitution.”

Clearly, when advising both Nelson and Tyler, SAIC understood that their imagery would offend certain sectors of the population, but to have censored the production and exhibition of their pieces would have been to censor ideas and issues that were important to them and important to their creative output as artists — an act that would have stood in direct antithesis to the nature of the School’s mission as an educational institution.

When it comes to peer censorship though, art educators are in a difficult position — as much as they should not be allowed to censor the content of student art, they are also in no position to be telling other students what they should and should not appreciate in the work of their peers. So how can a culture of respectful criticism exist in an institution dedicated to exploring boundaries and pushing the visual envelope?

SAIC Arts Administration and Policy graduate student (and Rhona Hoffman Gallery intern) Katlyn Hemmingsen believes that this is something that should be supported with the infrastructure of the school’s curriculum. “I think it is important to focus on the issue of censorship with students specifically because their situations are so unique — they especially should be supported regardless of their work content, because they are still growing and creating what they hope to be their future and voice, and more importantly, their message,” she said in an interview with F.

She continued, “I think the most kosher way to approach this issue is to place neutral, open-minded individuals in charge, and hope for the best. If regulations are placed, people will continue to fight them and find ways around them. It’s best in these situations to have open air.” Within this idea of open air is the notion that students should be sharing their work with each other and allowed to experience each other’s individual processes from conception to actualization.

Furthermore, not only is it important for student artists to know how their work is being experienced by viewers, but they also need to develop the skills to defend and discuss their pieces in a way that is critically sound. By that same token, those who are willing to be critical need to have the tools to articulate their analysis in a constructive and honest manner, rather than passively and subversively censoring certain pieces within a public sphere.

Furthermore, not only is it important for student artists to know how their work is being experienced by viewers, but they also need to develop the skills to defend and discuss their pieces in a way that is critically sound. By that same token, those who are willing to be critical need to have the tools to articulate their analysis in a constructive and honest manner, rather than passively and subversively censoring certain pieces within a public sphere.

Although frustrating, Lindquist understands that her postcards, and work, are going to be offensive to some viewers. “With that card, I can understand. I’m putting myself in someone else’s space, and I can see myself being upset about that a few years ago … seeing an image like that, and thinking that I know what that person is trying to do — the ‘shock value.'”

However, despite her use of potentially shocking material, Lindquist is adamant that the purpose of her work is neither to shock, nor to provoke negativity. “It really affected me when I knew that someone was taking down my images — that’s when I started realizing how personal this [work] was for me. It’s forcing myself to confront my own issues, so I can understand how confrontational it could be to someone else,” she said.

Whether or not the student who was sabotaging Lindquist’s imagery was one of her fellow students will never be known. Despit not knowing, when it comes down to it, all Lindquist really wants is the opportunity to defend her work.

If she came across the individual taking down her postcards, she “would honestly really want to talk about it. I wouldn’t get angry, because I can understand it. But at the same time, I felt like it was really disrespectful to censor my imagery. I would ask them why they were taking [the cards]. Is that something you’re wanting to keep? Or is it something that’s upsetting for you to look at?”

Arts education needs to include, and promote, communication and critical discussion between artists. In an age where rapid-fire technological developments are increasingly transferring art of all mediums to the internet, artists need to stick together — a message Lindquist is passionate about conveying. “As artists in Chicago, and in the SAIC community, we need to respect each other, and respect each other’s work. Because that’s what we do. And this is our art.”

Hey Fnews, I should be working on my thesis but instead I’m trolling your site. I hope everyone’s doing well. I think I might actually miss production weekend every once in a while, which is a testament to your ever-enduring awesomeness.

I just wanted to say a couple of things in response to this article: first, that the definition of censorship here is rather wide; second, that we don’t really actually need to respect each other or each other’s work simply because we’re all artists and “that’s what we do.”

Look, while not necessarily intrinsic to the definition of the word, censorship does usually imply action by some sort of authority. Censorship is systematized. You could argue that a person (or a bunch of people) turning over cards in the MacLean building is censorship because it removes images that the individuals (or individual) involved find offensive, but frankly this is more like protest. Or vandalism, if you want to be violent about it. At any rate, it’s not a particularly negative thing–the artist clearly wants a reaction, and she’s getting a reactionary response. Points on all sides. Art is not private, despite what the artist seems to think, and offering it for viewing means turning over control to the public.

Secondly, I don’t know what’s up with this touchy-feely “we need to respect each other and each other’s art” bullshit. No, we don’t. Respect is earned, your don’t get it just for making something, and if people (other artists!) think your art is stupid or offensive or both, then they certainly don’t have to respect it or you for making it. It being “personal” and “your art” does not make you imune. The scorn of your peers is something you should be prepared to accept, especially if you are going to inflict your particular brand of retarded pornographic pseudo-journalistic social commentary horseshit on the community. No one can (or should) stop you from making it or putting it up on the walls, but that’s where our responsibility ends.

Frankly, the fact that someone took the time to turn over all these cards or make them disappear is a resounding answer to the query posed by the exhibition. That is “discussion,” no?

Once, back when I lived in the dorms, I had a sign on my door that read: “I am the best chef” and some philistine assholes ripped it down out of jealousy on their way to make brownies on the 15th floor. My feelings were very hurt!

[…] from removing Lindquist’s advertisement postcards displayed in the school buildings. “Although provocative and graphically sexual, Lindquist’s installation is technically sophisticated […]