A look at photographer William Egleston’s first U.S. retrospective

review By Whitney Stoepel

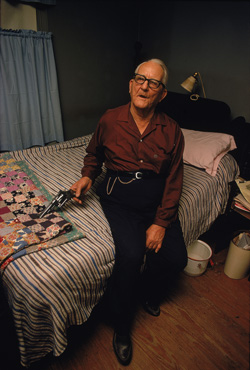

- William Eggleston. Memphis, c. 1969-70, from William Eggleston’s Guide, 1976, Dye transfer print, 15 15/16 x 19 15/16 in The Reader’s Digest Association, Inc., Pleasantville, New York. All Photographs © Eggleston Artistic Trust, courtesy Cheim & Read, New York.

After a long Chicago winter, it’s good to see color. The William Eggleston retrospective, “Democratic Camera, Photographs and Video, 1961-2008” at the Art Institute of Chicago is a fitting way to celebrate the return of spring.

Organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and Haus der Kunst in Munich, this exhibition is Eggleston’s first retrospective in the United States. It is expansive, filling the Abbott Galleries and Carolyn S. and Matthew Bucksbaum Gallery in the Modern Wing.

The title of the exhibition comes from the legendary photographer’s idea of photography as “a democratic way of looking around. Nothing was more important or less important.” While this perspective isn’t ground-breaking, Eggleston is renowned for his early adoption of color photography as a legitimate art form.

“Democratic Camera” contains all of Eggleston’s notable color photographs of the American South, including such famous images as “Red Ceiling” (1973), a ceiling drenched in blood-red paint with a light bulb tethered by creeping wires. Also on display are that recognizable tricycle looming above the camera on an empty suburban Memphis street, and the neon confederate flag.

But the show delves much deeper than those famous images — it also includes earlier black and white photographs from the early sixties, the rarely seen “Stranded in Canton” (a video shot on a Sony Portapak that documents Memphis and New Orleans in 1973), journals with his abstract drawings, and recent digital prints.

- William Eggleston. Morton, Mississippi, c. 1969-70, from William Eggleston’s Guide, 1976. Dye transfer print, 13 3/8 x 8 11/16 in (34 x 22 cm.) Cheim & Read, New York.”

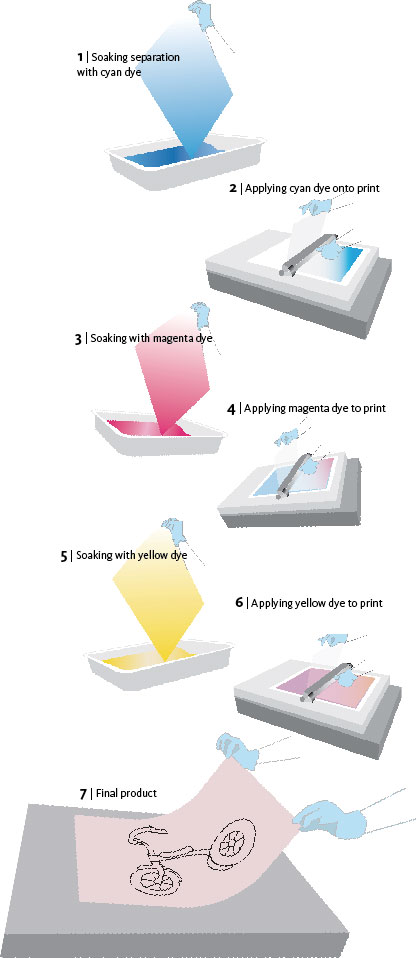

The range of this retrospective reveals the importance of this artist to the history of photography as an art form. When Eggleston began printing using the dye-transfer process it changed the way artists thought about color photography.

His first published book of photographs, “William Eggleston’s Guide” (1976), was accompanied by the first ever one-person exhibition of color photographs at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Artist John Szarkowski, who wrote the text for the book, explains how photographers were baffled by the dawn of artistic color photography. In short, after spending a century perfecting the medium in black and white, photographers suddenly had access to cheap color film, which had first been intended for commercial purposes.

The 1976 exhibit also eatured a quote from Janet Malcolm, in which she compares color photography to “retrograde applications [such as] advertising, fashion, [and] National Geographic travel-type pictures.” The book itself and most of its photographs are on display in the AIC retrospective.

The process of dye-transfer printing is extremely complicated, but most photographers and critics agree that it is unparalleled in its ability to showcase chromatic nuance. Photographs appear hyper-real — the visual effect is sometimes compared to Technicolor. This method of printing is also admired for its accuracy and stability in a wide range of temperatures and over long periods of time.

Although his printing process is complex, Eggleston’s subjects never were. “William Eggleston’s Guide” is a series of simple (if not mundane) moments from his hometown of Memphis and the surrounding area.

Rarely are there more than two subjects in a photograph, and they are always represented in their own surroundings: sometimes a backyard, sometimes a gravel road, sometimes an empty suburban street or bedside. Every photo brings with it a quiet feeling of isolation, and even pictures taken outside of the artist’s hometown convey a sense of familiarity.

This exhibition is separated into chronological themes, including his photographs of the South from “Guide,” as well as the “Los Alamos” series (1965), “Election Eve” (1976), “Graceland” (1983), and “Democratic Forest.”

Eggleston has said that he never takes the same picture twice. If he has a roll of 36 exposures, he will have 36 different pictures. This roving, impulsive eye is apparent when the viewer examines his work from any locale.

The subject of Eggleston’s photographs isn’t always centered, and sometimes the entire frame is skewed; but in spite of the apparent simplicity of the imagery, the artist is adamant that his photographs were not “snapshots.” In fact, he doesn’t even believe in the word itself.

In his book “Democratic Forest” he writes, “I am afraid that there are more people than I can imagine who can go no further than appreciating a picture that is a rectangle with an object in the middle of it. … They want something obvious. The blindness is apparent when someone lets slip the word ‘snapshot.’ Ignorance can always be covered by ‘snapshot.’ The word has never had any meaning. I am at war with the obvious.”

- William Eggleston. Memphis, c. 1969-71, from William Eggleston’s Guide, 1976. Dye transfer print, 24 x 20 in (61 x 50.8 cm.) Collection of John Cheim.

Particularly revealing in this exhibition are the journals that contain colorful drawings which evoke Kandinsky, Eggleston’s favorite painter. When Ann Landi of ARTnews asked him if the drawings were related to his photography, the artist replied, “Does not tie in a bit. … The abstracts are absolutely not connected in any way whatsoever with the photographs.” Indeed, although the drawings reveal a wild and saturated use of color, like his photographs, that is where the similarities end.

Eggleston not only dabbled in drawing; he is also a musician. As a child, living on a cotton plantation, he believed his future was to be a concert pianist, and his work has always had ties to music.

In a display case at “Democratic Camera” lays a record cover for the Memphis band, Big Star, a band that Eggleston has accompanied on piano. The cover of the LP “Radio City” features Eggleston’s photograph “Red Ceiling.” His work has graced many other album covers as well, including covers for artists such as Joanna Newsom and Spoon.

In another connection to the music world, Eggleston was the photographer for Talking Heads front man David Byrne’s directorial debut, “True Stories,” and these images are also on display. In Eggleston’s book “Ancient and Modern,” Byrne said, “I find these pictures pleasantly disorienting. Some look like accidents, like somebody accidently pressed the shutter button on the camera while examining the strap, or something.”

To truly appreciate this exhibition, visitors should drop by the Art Institute twice. Because of its enormous size, but also because the retrospective demands serious contemplation on this artist’s lifetime of work, even if the work itself is not inherently complicated. Eggleston said it best in Michael Almereyda’s film, “William Eggleston in the Real World”: “Art… you can love it and appreciate it, but you really can’t talk about it. Doesn’t make any sense.”