“Education can be an important art experience but an art experience is not dependent on an educational experience or an educational background.”

Interview By Beth Capper

Paul Chan’s face, or at least part of it, is on the cover of F Newsmagazine. It’s March 1994, and the lead article of the issue is a piece Chan wrote debunking the concept of Generation X. Defined as the generation born between 1961-81, Chan, born 1973, comes smack in the middle, and as such he’s writing about his generation. Yet, reading his words in 2010, they are oddly timeless. “Each generation produces their own winners and losers. And X is no different,” he writes. “…It is time to stop age-bashing, and to see Generation X as merely a group of individuals trying to find their place in the American landscape—a landscape of economic uncertainty and cultural disjunction.”

Substitute Gen X for Gen 2.0, and Chan could just as well be writing about many of us. And with shows such as the New Museum’s “Younger Than Jesus” exhibition and books like Tao Lin’s “Shoplifting from American Apparel,” the need to express the essence of the current generation is ever-present.

Art students can learn something from his trajectory. His relationship to art grew as much from his rejection and frustrations, as by his participation in it. This is, in part, how he came to work for two years as an editor for F—seeing the newspaper as a refuge from the rest of the school, a place to question the value of art and express his own opinions on art and other matters in freewheeling editorials.

F was also the place where Chan began to get interested in politics—an interest that has endured in his art practice, even though he makes a point of expressing that his activism and art are distinct. Still, from works such as Chan’s “Tin Drum Trilogy” of empathetic video essays about U.S political figures, Red State citizens and “othered” Iraqi nationals to his decision to situate a production of Samuel Beckett’s “Waiting for Godot” in post-Katrina New Orleans, his work expresses a decidedly activist spirit even if the intended outcome is different.

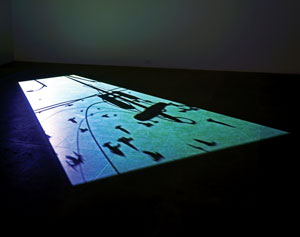

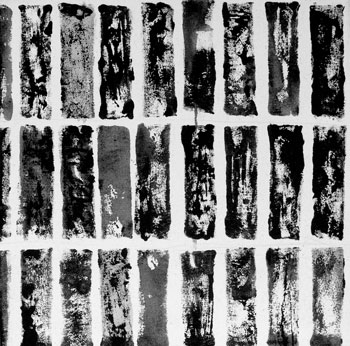

Over the years, Chan has created a disparate body of work that spans New Media animated gif. art to installation, video and collage. In addition to his vast art practice, he also writes copiously—recently published articles include an interview with Adorno scholar Robert Hullot-Kentor and an article about “What Art is and Where it Belongs” for the online journal E-Flux. I sat down with Chan at his studio in Sunset Park, Brooklyn, nearly fifteen years after he left SAIC.

BETH CAPPER: Tell me about your experiences at SAIC.

PAUL CHAN: When I think of the Art Institute I always think of my favorite quote from Mark Twain, who said “Never let schooling interfere with your education.” I think in a way I came at a time when I needed a place that would give me a lot of freedom so I could learn on my own, and the Art Institute gave me that, so I got a lot out of it. I didn’t make a lot of art when I was there. I didn’t expect or maybe even want to be an artist when I left. It took me some time to connect to the idea of being an artist. That was definitely something I committed to after school. At school I was just learning to survive in the city. And learning to learn, and to try as many things as I can. F was familiar —in high school I did journalism a lot. It gave me a place to be. It helped me escape from the rest of the school, and it was rightly or wrongly a kind of refuge for people who didn’t know their place in art.

BC: Do you maintain the same skepticism in relation to the artworld?

PC: I think skepticism is always healthy, so, yes, but I think most artists worth their salt have that skepticism built in. To believe in art is to already give up on it. I learned a lot of that skepticism at school. And I learned a lot of that on F actually, because Paul [Elitzik, F Newsmagazine faculty advisor] was a big philistine. I think his attitude was an important antidote in many ways and what many young artists should be exposed to. It’s not that he hates art, only that he was more insistent on questioning its value and its worth and I think that is important every step of the way. It was his contrarianness that was attractive. I think at the end of the day that he provided an important perspective in an art school. You go into art school at nineteen, and what you know of art…. what I knew of art, was from the one museum in my home town. It’s not like you have a comprehensive view of what art is or what it wants to be, and so you get thrown into this world in which art exists but you have no real substantive understanding of what it is. You don’t know how you relate to it. And no-one tells you that—no matter how many art history books you read. It’s really a philosophical question and one you always assume that you know, and so this assumption is there and you go on. With Paul and other people on F, that wasn’t an assumption. It was an open question as to what value art does in fact have—in pedagogy, in exhibition and in writing.

BC: Are you interested in pedagogy?

PC: Education can be an important art experience but an art experience is not dependent on an educational experience or an educational background. In a weird way, for me, art troubles everything we know about education. On the other hand, I think it’s important for people to know and learn about the past, and the context that they exist in. It was important for me to hear Lisa Wainwright talking about art. When I went to school she was just an art history professor. Listening to her talk about Degas or Cézanne was important, because whether we believed it or not, that was the tradition in which we found ourselves, and if we’re serious about being artists we need to understand this tradition and understand how they dealt with being artists. I think most good artists take some position about pedagogy. Do you know who Charles Barkley is? He used to play basketball—he was a professional basketball player, and he played for the Boston team. He’s slightly big and he’s a loudmouth. And when he was big in the NBA, he was famous for making these commericials where he would keep saying he’s not a role model, as a kind of suckerpunch to Michael Jordan. Because they always saw Michael Jordan as a role model—because we’re a puritanical country we always need role models for kids. And Charles Barkley said, “Fuck you, I’m not a role model, I’m just a basketball player.” When he’s saying that he’s already taking a position on whether he’s a role model or not.

BC: Tell me about your interest in quotation and literature.

PC: I think it would be hard if I used things I didn’t like. And I think you can feel it when people do that—they use something that they feel is important but they don’t necessarily have a connection to. The things I use, I use like anything else. Because I’m pleased by it somehow. The challenge is almost to use it a little ruthlessly. It’s not fidelity I’m trying to preserve. It’s the spark that comes from ripping it from its context and using it in a different way. There are times when that kind of picking and choosing is not compelling and most of the time that is because you are not ruthless with it.

BC: Is there anything you read that you consciously keep separate from your art?

PC: I would like to think that nothing is off the table. There is a kind of equality to it. Everything is equidistant. It’s terrifying in some ways but if you can do it in a way that makes someone feel potentiated…

BC: Why is it terrifying?

PC: Because of the tyranny of equality. Because if everything is equal, it may mean that nothing has real significance. I think that’s OK and that it’s liberating. But at the end of the day we may not be able to live like that.

BC: That’s interesting in relation to your use of New Media, in that New Media theory would seem to posit that there is no difference between things and that actually there should be no difference. How do you feel about that?

PC: The plainest answer is that it doesn’t matter how we sit with it. It’s just how we sit. Offering a perspective may be helpful, but it doesn’t get to the heart of it, which is simply that that’s how it is, whether we like it or not. So, I guess the second question is: Are you willing to sit with it? There are so many people who do collage, who do bricolage, who combine found materials into some sort of composition, but the aesthetic challenge is to do it in a way where it can be remembered. Online you see all these people combining things, and when you look at these things something happens and you realize, “Oh, some things are better than others.” Things are different.

BC: What do you think of relational aesthetics?

PC: I think it was an interesting movement that came at a time when the world needed a way of thinking about how it was changing from a manufacturing economy to a service economy, and to an information economy. The engine of the economy in the U.S up until the 1970s was making things. It was from the 1970s on that our economy changed from making things to servicing people. And we needed new paradigms and models. This is the same time that in the art world you see a dematerialization of art. I think it was an artistic response to the image of what it means to live in a service economy. What one sees is a kind of service in these works—you’re being served, like in Carsten Holler’s hotel. What is up for debate is whether it’s an actual community, but what is not up for debate is the sense that you are being served.

BC: Do you believe in the idea of community?

PC: Do I believe in the idea of community?!?

BC: Yes.

PC: Did Paul put you up to that question?

BC: No. I’ve been reading a lot of Jean-Luc Nancy.

PC: Oh geez. That’s interesting. I have been thinking about this idea recently. One of the great things about the project I did in New Orleans is that after I left some of my students started a co-op gallery, and I have been supporting them as much as I can. I’ve donated some work to them and such. They’ve existed for almost a year, and they are putting out a catalog and they asked me to write an intro. And for the intro one of the things I want to do is to think about this idea of community, and I think the idea of community is an important one—everyone wants it but no-one knows how to get it. It’s like love—everyone wants it, no-one thinks what they have is it, and you always want more of it. Nancy was, if I’m right, reacting to something that Bataille wrote. Bataille wanted to kill someone to create a community and that’s insane. But what’s not insane is the idea of sacrificial value—that community coheres when everyone shares something that is intense. We see this idea of sacrificial value all the time…

BC: Revolution?

PC: Revolution. Katrina. People sacrificing thousands of people and bringing other people together in the process… Haiti. So Bataille was not that insane. My question is: Is it possible to create social value without sacrifice? And I think that’s a question, you know. And some of the people who have tried to answer this question are the relational aesthetics people, and their answer is service. That you don’t need sacrifice as long as we give you something, but that giving may not feel so giving.. it feels transactional. It feels like a service.

BC: Talk about your activism. It seems like, in contrast to your art, you have an old school idea about activism.

PC: I guess my notion of activism is pretty old school.

BC: It’s a Paul Elitzik idea of activism?!

PC: Err, ha. Well, yes, I guess it is in many ways. It’s closer to that than I might like to admit. Have you talked to Paul about his political affiliations?

BC: A little.

PC: He went to City College here [in New York], then he went to Harvard to study classics. Then he did labor organizing in a shoe factory. I think when you have those kind of experiences, it really embeds itself in you. In how you treat people, in how to not treat people. I think my experience in politics comes solely from my experience with activists and politicians. It has a kind of real world insistence that I refuse to give up, even while I am exposed to so many ideas that contemporary artists and thinkers have. It’s not either/or. You can make it work. You just have to be less judgmental.

BC: What’s next for you?

PC: I’m retiring. I’ve finished a show at Greene Neftali and I’m starting to release some things online. And then I’m done. I’ve made a coffee table, and I made that lamp behind you.

BC: Really?

PC: Yes. I have no plans.

BC: Why are you retiring?

PC: Real beginnings demand real ends. I think the world is big, and I can do a lot of different things. I want to believe that we are not beholden to certain things.

BC: What are you gonna do now?

PC: If it’s any indication, I’m going to make coffee tables and lamps, and I’m going to be writing a lot of emails.

Other Resources:

“What Art is and Where it Belongs” by Paul Chan for e-flux

Robert Hullot-Kentor with Paul Chan by Paul Chan, The Brooklyn Rail, March 2007

In Conversation with Paul Chan: his own private Alexandria (v.1) , Newsgrist, April 21, 2006

Paul Chan by Nell McClister in BOMB 92/Summer 2005,

[…] interview […]