“Italics: Italian Art Between Tradition and Revolution” at the Museum of Contemporary Art

By Ania Szremski

“I’m a curator, not an art historian…and the two things are completely different.” Francesco Bonami’s comment on his latest blockbuster exhibition at the MCA is the first indicator of the surprisingly personal, intimate nature of what might otherwise have been a typical encyclopedic show. “Italics: Italian Art Between Tradition and Revolution (1968-2008)” is certainly an attempt to chart a chronology of artistic production in Italy over the past 40 years, but perhaps more interestingly, the show narrates a melancholic tale of artistic careers that traditional art historical narratives have elided—a story crafted from personal histories and nostalgic recollections.

Developed in conjunction with the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (where it was shown in 2008), “Italics” is the sequel to Germano Celant’s “Italian Metamorphosis: Italian Art from 1943 to 1967,” at the Guggenheim in 1995. The intention of both curators was to make visible a century of work eclipsed from view. While seminal movements like Futurism and Arte Povera managed to make the leap into the international sphere, the majority of Italian artists passed unobserved outside their native country. Operating without an established infrastructure for contemporary arts, in an often oppressive political climate and during times of economic duress, these artists were even further burdened by the crushing weight of their cultural patrimony. Compound this problem with certain latent prejudices in European and North American scholarship in the 20th century, and mid-century Italian artists were faced with almost insurmountable obstacles to recognition, even at home.

Developed in conjunction with the Palazzo Grassi in Venice (where it was shown in 2008), “Italics” is the sequel to Germano Celant’s “Italian Metamorphosis: Italian Art from 1943 to 1967,” at the Guggenheim in 1995. The intention of both curators was to make visible a century of work eclipsed from view. While seminal movements like Futurism and Arte Povera managed to make the leap into the international sphere, the majority of Italian artists passed unobserved outside their native country. Operating without an established infrastructure for contemporary arts, in an often oppressive political climate and during times of economic duress, these artists were even further burdened by the crushing weight of their cultural patrimony. Compound this problem with certain latent prejudices in European and North American scholarship in the 20th century, and mid-century Italian artists were faced with almost insurmountable obstacles to recognition, even at home.

Resurrecting the reputations of these lost generations and inserting them into a dialogue with more canonical Italian contemporary artists is certainly a noble goal, but within the confines of one exhibition seems overly ambitious—“Metamorphosis” was lauded for its intentions, but disappointing in its execution. Fortunately, however, Bonami managed to exercise a restraint that Celant wouldn’t (or couldn’t). “Metamorphosis” overwhelmed the viewer with over 1,000 objects ranging across disciplines (from painting and architecture to craft and fashion) as the curator strived to present a panoramic vision of that period. Bonami, on the other hand, constructed a more clearly focused thesis for his show, with roughly 77 artists representing genres including photography, performance, video, painting, sculpture and installation. Organized around themes that are, to be frank, fairly stereotypical markers of Italian identity and experience (including family, landscape, design, political unrest and constructed environments). “Italics” leads the viewer through a fairly subjective chronology of artistic movements in the latter half of the century. The show covers Arte Povera and the Transavanguardia through neo-avant garde, post-pop, and the relational works of some of the younger artists.

“Italics” begins with Maurizio Cattelan’s unnerving, but beautifully compelling “All” of 2008: a series of nine pristinely white marble sculptures representing shrouded, anonymous recumbent corpses, neatly lined in a row. In a way, it seems a bit disingenuous to open a show dedicated in part to championing unknown artists with one of the contemporary Italian art scene’s most recognizable names, but thematically, “All” encapsulates the dynamics inherent in the exhibition. The piece is immediately attention-grabbing; particularly in light of contemporary events, the sculptures call up very recent, anxiety-laden visual memories. However, a closer look reveals that these are not just evocations of death and suffering, but beautifully carved figures swathed in masterfully rendered drapery; and, of course, the figures are carved in that favorite medium of the Italian Renaissance, pure white Carrara marble. The piece hardly “puts to rest the ghosts of the Renaissance and Baroque,” as the MCA would have it; instead (and in a much quieter way than Cattelan’s more aggressive, political works), “All” poignantly bears witness to a relatively young artist’s grappling with contemporary issues, his own identity as an artist and the oppressive burden of an inescapable cultural heritage.

A tension between polarities informs much of the work on view: the yoke of patrimony and the desire for new territory; nationalist political narratives and personal stories; the monumental and the intimate; slick design and humble craft. In terms of the ways in which the represented artists engage these tensions, visitors shouldn’t expect to be shocked by any earth-shattering discoveries; there’s nothing profoundly ground-breaking in terms of what the art does. That doesn’t quite seem to matter, however; “Italics” succeeds in that it offers up compelling, engaging work that is not just representative of “Italian” issues, but that constructively contributes to expanding the global art historical narrative that has ignored it.

There are, of course, the inevitable jarring notes. Bonami has already been criticized in Italy for including unknown painter Pietro Annigoni’s “Autoritratto (Self-Portrait)” of 1985, a conventional, easel-sized oil painting executed in the tradition of Rembrandt self-portraits. This three-quarter view of the somber, bespectacled artist is executed in painterly baroque style and evidences studious attention to things like chiaroscuro; it feels downright anachronistic for 1985. The curator defends his inclusion of this relatively banal work by defining it as emblematic of an artist constantly striving to meet the standards of the past, but never quite measuring up. The painting isn’t entirely without merit, but despite Bonami’s defense, it simply doesn’t gel with some of the more experimental, thought-provoking works in the show.

Similarly out of place is Massimo Grimaldi’s slideshow from 2008 in the gallery devoted to revolutionary politics, youthful dissension and violence. “Emergency’s Surgical Centre in Goderich” consists of a series of photos of children undergoing medical treatment at a facility in Sierra Leone, displayed on two iMacs. Stress has been laid on Grimaldi’s charitable efforts and the fact that he often donates proceeds from the sale of artworks or commissions to this hospital, which is all well and good; but the piece itself lacks the frenzied energy of the works that surround it, no matter how noble Grimaldi’s political conscience. “Emergency” doesn’t read well next to Letizia Battalgia’s disturbing (and ethically questionable) photos of mafia violence in Palermo and Cinisi, Tano d’Amico’s photo series of student protests in Rome from 1974 and 1977, or Francesco Clemente’s iconic, photocopied drawing of a fist-wielding, frizzy-headed youth.

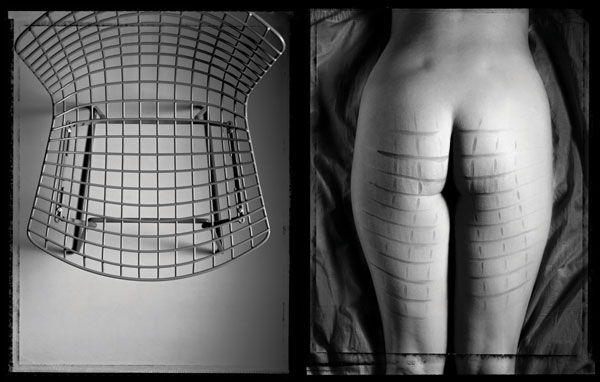

The probably inevitable discordances are, however, balanced by some stand-out works. For instance, Lucio Fontana’s “Ambiente bianco (spaziale)” (recreated installation of 1968), transports the visitor to an ethereal environment that truly feels like a realm apart; similarly, Micol Assaël’s “Your Hidden Sound” is a profoundly disorienting installation in which the viewer enters a room of impenetrable darkness, where space is carved up into a grid by white cords glowing in the black light. These immersive installations successfully communicate a hallmark interest in design and built environments, as well as an emphasis on viewer participation, that is, once again, revelatory of the historical and contemporary tensions inherent in modern Italian art practice.

The film and video works in “Italics” are particularly interesting. Berlin-based artist Rosa Barba’s video projection “Outwardly from the Earth’s Center” of 2007 is a captivating, dream-like visual exploration of an island that is drifting away from the mainland as its inhabitants attempt to stabilize this shifting ground. The film is much like one of Werner Herzog’s documentaries, juxtaposing ethereal sequences that depict nature’s inherent violence towards man with interviews with “scientists” and “specialists.” The result is a kind of oneiric archive that blurs the line between document and spectacle.

In striking contrast to Barba’s film is the intensely sensual subject matter of Domenico Mangano’s “La storia di Mimmo,” a film from 1999. “Mimmo” is a graphically intimate portrait of the artist’s obese uncle’s solitary and slothful existence; cloistered in his apartment (more often than not in the nude), Mimmo is shown alternately talking about food, eating, talking about food some more, grunting maniacally and, from time to time, bemoaning his wasted life. The man has a larger-than-life, grotesque and buffoonish quality, and the video is downright uncomfortable in its ultra close-range examination of his existence (even documenting the subject as he continues his eternal feast on the toilet). Underneath this outrageous, baroque sensuality, however, the piece has a wistful, almost tragic register; it feels like a document of loneliness, of regret for unrealized opportunities, for what-might-have-been.

Food seems to constitute another one of Bonami’s stereotypical markers of Italian identity; extracts from Vanessa Beecroft’s 1993 “Book of Food” continue with the theme. Beecroft, of course, represents the notoriously successful contingent of Italy’s young contemporary artists, and her “Book of Food” performances have been the target of vehement feminist critique. In “Italics,” however, the emphasis is on Beecroft’s small-format, delicately rendered line drawings and water colors, as opposed to controversial performances of young emaciated girls in their underwear. The drawings serve as incredibly poignant testimony to the artist’s neurotic obsession with alimentation; as opposed to the slick fashionista aesthetic that has come to be equated with Beecroft, these drawings feel remarkably vulnerable.

It is works like these that make “Italics” an exhibition worth re-visiting. Compared to other marginalized artistic practices of the same period, these pieces may at times feel disappointingly safe; but they provide compelling testimony to a generations-long struggle for the assertion of a new, generative cultural identity, a struggle that certainly has implications that reach far beyond national borders.