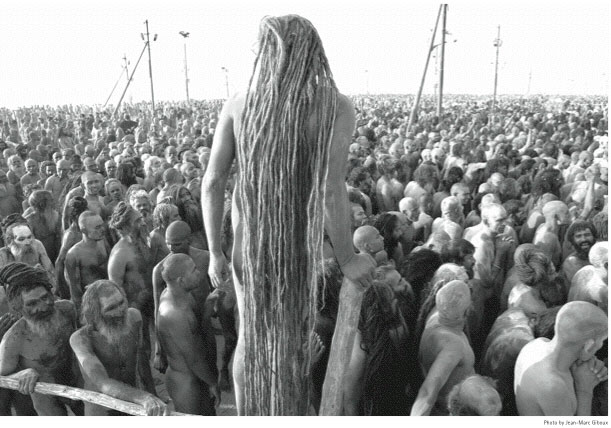

Photos of faith in movement

“Sacred Waters” at the Field Museum

“The independence of the journalist is a myth,” says Jean-Marc Giboux, over a café au lait in Wicker Park’s Café De Luca. I cannot remember if he said it in English or in French, but I am excited because that is a great, sweeping quote and I have never really interviewed anyone before. He is speaking about his photography work, which is stunning. “You have to be in the moment to take photos, you have to feel things…” he follows up.

Mr. Giboux’s photography exhibition, “Sacred Waters: India’s Great Kumbha Mela Pilgrimage,” opened at the Field Museum on March 5 to a small crowd of cultural relations people. It is one of the few shows to have opened in the Marae Gallery on the second floor of the Field, in which the work actually seems too big for the space. Giboux’s photography is riveting. It displays a worshipful veneration of humanity, of a magnitude that is not often witnessed in the Western world.

The photos document the Kumbha Mela, Hinduism’s biggest event, and the largest religious gathering on earth. The pilgrimage spans four different holy sites, with one visited every three years, following a 12-year cycle. Giboux’s involvement with it began in 1998 when he went to shoot it with the Gamma-Liaisons photo agency, for whom he was working at the time. He tells me he went four times and was supposed to stay for a week, but he was so taken with the experience that he ended up staying for a month. What attracted him, he says, was “the India of villages, traditional India.” He speaks of socializing with people to gain their trust so that the photos would be honest. “At first, when you come to India as a Westerner you’re the center of attention,” he explains, but with time people get used to the interloper, which is when he starts to take pictures.

He deplores the trend among the younger generation, mostly brought on by the incursion of Western companies on tribal land, to reject their cultural attachments. “Looking into Indian culture,” he told me, “the kids spend so much time in the virtual world, and they create stories there, as if the real world had nothing rich enough for them.”

There is something of the turn of the century adventurer in Giboux, though he tells me repeatedly that what he does is not glamorous. He likes projects with a wider scope, because they present him with the unique opportunity to step out of day-to-day modern life and into an experience that is utterly alien. While shooting the pilgrimage, he tells me, he lives on the ground. He sleeps on it and eats on it like everyone around. He spends a month away from the Internet—which to most of us is hopelessly exotic—and keeps a hotel room not for himself but for his photo material and the occasional shower. “People idealize this sort of life, but most people probably couldn’t do it.”

Giboux started taking pictures in high school after a drawing instructor gave him a demonstration. The gift of a Nikon F from an uncle cemented his fate, and he learned as much as he could on his own, due to the dearth of photo programs in France at the time. In the mid-80s, he relocated to the United States—Los Angeles specifically—in order to cover news, social issues and cultural trends in LA for various European publications. Giboux worked with current events—specifically gang violence and societal problems—for several years. America, he says, was like a laboratory for Europe at the time.

France was perhaps a decade behind the U.S. and picking up all its bad habits, so being on hand to watch as the cultural force behind the modern world developed was a singularly privileged experience. Doing news work was draining however, “because you have to do it all the time, you can’t turn it off.”

His interest in people and cultural phenomena seems to have lingered however, because while he began to work on more large-scale projects his strong humanist bent brought him to several humanitarian endeavors: for Doctors Without Borders he shot immunization campaigns, and for the World Health Organization he documented the attempt to eradicate polio. Throughout his photos and in his manner of describing what he does, the most obvious trait is a strong sense of integrity, coupled with a deep compassion and genuine interest for his subjects. “There needs to be meaning in your art,” he tells me. “I need emotion in my photography. Good light, good composition and emotion.”

When I ask him about funding, he smiles and tells me that that was obviously the most difficult part. Outside of a major grant he got from the Rotarians to shoot the polio project and a couple of excursions with Doctors Without Borders, his projects are mostly self-funded in a poetic Robin Hood sort of way, by his corporate work done in the States. He does not particularly enjoy shooting corporate events (he says he prefers to be an adventurer), but his attitude is that you do what you have to do in order to get to what you love.

I tell him about my own attempts to find balance between my professional life and my artwork, and he tells me that there has to be some compromise, but that anything is possible. That sort of statement usually sounds patronizing, but I believe him because he reminds me a bit of Indiana Jones, and his photos are so honest that I cannot help but think he might be onto something. After all, the work in “Sacred Waters” feels real; presenting a working artist doing it right.

I’m privileged to know Jean-Marc and his job for some years. Great artist, great humanist, amazing work of integration in different cultures, resulting in colorful emotional images that I love so much. Unfortunately, I don’t know if I’ll be able to see his pictures in the walls of this Museum, but I’ll do my best to attend.

I’m very please to read the words of the interviewer (whom I don’t know) as he speaks very well about Jean-Marc, his work and vision of life. This is the guy!

I wish all success to the exhibition and I hope Jean-Marc will get more means out of it, to continue to build his testimony, witnessing of things we probably wouldn’t be able to live and that he does on the humanity behalf.

[…] an interview with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Jean-Marc told the interviewer that funding was […]