It is no secret that the arts in this country have been on the defensive for years. Across the board, the arts have been the first line on government spending budgets to be slashed. From arts education programs at elementary and high schools to its pathetic give-and-take policy of endowing then-unendowing the NEA, government policy has shown that it (dis)regards the Arts as expendable.

The devaluation of the arts in the U.S. has forced arts professionals and organizations to rely on ingenuity and argument to survive, forcing the art world to develop into the commodified system that artists constantly bemoan (cultural Darwinism, can we say?). But now, as we find ourselves firmly entrenched in a financial crisis, the arts have found themselves under targeted, brutal and often stealthy attack.

On February 6, the U.S. Senate approved by overwhelming majority (73-24 votes) the Coburn Amendment to the economic recovery bill under its consideration, which states: “None of the amounts appropriated or otherwise made available by this Act may be used for any casino or other gambling establishment, aquarium, zoo, golf course, swimming pool, stadium, community park, museum, theater, art center, and highway beautification project.”

Besides the egregious correlation made in this amendment between gambling, highway beautification, golfing, art, theater, and animal refuges—i.e. the collapse of luxury entertainment and culture into one—this amendment assumes that bolstering the arts would do nothing to bolster the economy. It also displays an utter disregard for the well-being of these foundational institutions, myopically marking the arts with the stereotypical, regressive and ignorant stigma that they are superfluous and self-indulgent.

This amendment has since been amended, and the final version of the economic-stimulus bill approved by Congress on February 13 removed the arts organizations from the clause. However, the argument made to rescue the arts organizations from the grouping by Representative David R. Obey (Dem., Wisconsin): “There are five million people who work in the arts industry. And right now they have 12.5 percent unemployment—or are you suggesting that somehow if you work in that field, it isn’t real when you lose your job, your mortgage or your health insurance?” implies that the arts have no intrinsic value and does not explain why the poor zookeeper still doesn’t seem to matter.

In a separate but ideologically parallel move, during the last week of January Brandeis University—whose reputation is based on its expansive liberal arts offerings—betrayed its legacy, when its board of trustees voted unanimously to close the school’s Rose Art Museum and sell off the 6,000 works of art in its collection.

Treating its priceless and historic collection of art as disposable assets, Brandeis made a stark statement about its priorities and an astonishing value judgment about the place and worth of art.

There is a lot more to be said about this decision, the reactions of and effects on the students and museum employees, the legal issues regarding by-laws and the subsequent backpedaling of the administration, as well as the dire financial situation in which the university has found itself (due to the fallout of the Bernie Madoff scandal). However, the statement their actions made is clear, and it has forever changed the perception of Brandeis’s commitment to the arts. But more so, it reflects and supports the widely held, but rarely explicitly stated, belief that the arts are dispensable.

Now, I realize that to argue for the pure value of the arts, as an Art Historian for whom they are a life blood—inspirational, motivating, and, most of all, essential—I will never convince anyone of their merit who believes that they are superfluous and self-indulgent. That is just their loss, though. However, if we are entrenched in a battle that prizes money and economic stimulation as its holy grail, then I am more than happy to argue that arts organization are among the most important, immediate and mutable agents for kick starting our economy.

Public art projects, museum exhibitions, non-profits and many other arts institutions create jobs across all industries: they demand catering for events, various forms of fabrication (steel, paper, electronic, etc.), the assistance of technicians, designers, lawyers, printers, accountants and brokers, and provide steady employment and income for numerous individuals and families. Their needs are flexible and the events they generate are either cyclical or singular ones that can be quickly put into production.

Need historic proof that the arts can bolster the economy? Look no further than the WPA. In addition to creating numerous jobs during the Great Depression, the artists employed by the WPA shaped an ideology and imagery that gave voice to a disenfranchised and downtrodden generation. The iconography they created has become integral to our understanding of what it is to be American; a historical imagery that we cannot imagine ourselves without.

If the majority of Americans want to send culture to the waste basket, I say they are just quickening our clip towards an idiocracy. But, if we want a strong, intelligent, moral, critical and well-informed populace—a true land of the free and the brave—then we must defend the arts with all our strength,

because they are our backbone, our foundation. As Dana Gioia, the chairman of the NEA, recently said, “The purpose of arts education is not to produce more artists, though that is a byproduct. The real purpose of arts education is to create complete human beings capable of leading successful and productive lives in a free society.”

When all else is taken away from you, all you have left is your education. Math and science just are not enough: who pursues happiness through them alone? What kind of heritage do we have without art? If burning books would give us some extra cash to throw around for the next couple of years, would you be willing light the bonfire? So why would you be willing to prevent their production—especially when the publishing companies increase circulation in the economy?

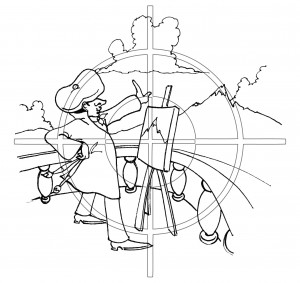

Illustration by