M*A*S*H gives a D*A*M*N

Before anyone recoils in horror, let me remind you that Robert Altman’s 1970 masterpiece has very little to do with the preachy wreck Alan Alda wrought later in the TV show’s existence, which is the period most of us are familiar with.

The movie is insane. In the best possible way, but it is insane. In fact, it wasn’t even directed—in true late sixties spirit, Robert Altman allegedly proceeded to confuse, bully, and alienate his lead actors (a particularly gorgeous and disaffected Donald Sutherland and Elliott Gould) until they were on the brink of mutiny. He then filmed it and sent that to his editor. I’m not certain that most of the film even had a script. The actors were encouraged to improvise and talk over each other, and do things like punch each other in the face without warning, which resulted in brilliant chaos—the sort that you couldn’t direct if you tried. And that was perfect, apparently, because it was the best commentary anyone could make on the debacle that Vietnam had turned into by the time the movie was being shot.

M*A*S*H, is the story of an army mobile hospital unit during the Korean war, was deliberately made to feel like Vietnam, down to the cone-shaped hats worn by the passer-bys in the one scene taking place in Seoul. The characters were closer in attitude to the kids being shipped off to ‘Nam than to the older soldiers who had been in Korea. The film follows the exploits and cheeky high jinks of Captain Hawkeye Pierce (Sutherland), who doesn’t care, and his fellow army surgeons, nurses, and radio operators, who similarly do not care because they can’t care without going insane. The one character who attempts to take himself seriously, Major Burns (Robert Duvall), is carted off midway through the film in a straightjacket; there is no respite from the constant aimless ridicule that angles all the way through the film and touches everyone from the harassed chaplain to the rigorously disciplined but ultimately defeated head nurse.

A series of bizarre and seemingly unrelated events happen over the course of Hawkeye’s one-year tenure in Korea: he steals a jeep, he plays golf, he drives his tent-mate insane, he passes himself off as a heart specialist and gets airlifted to Japan, he saves a few lives and loses a few lives, and then he hops into another stolen jeep, leaving everyone behind. The only cohesive element in the film is a series of preposterous loudspeaker announcements where a stuttering news operator reads out and mispronounces events, entertainment, news, high-pitched warbly Korean pop music, including a public service announcement about the dangers of marijuana, as well as a suggestion for army personnel to stop using it.

The film doesn’t try to make a point of the general pointlessness of the conflict the denizens of MASH #4077 are involved in (despite the uplifting “Suicide Is Painless” theme song), it just embodies it. It does exactly what good filmmaking is supposed to do: it doesn’t tell you something, it lives it. When asked how such a specimen as Hawkeye came to be in the army, the Sergeant in charge answers with a surprised, “He was drafted.” There is no reason, just a blind lottery. And there’s not much we can do to change that.

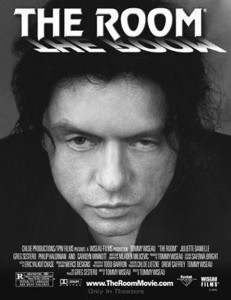

The Room with a view to crazytown

For those of you unfamiliar with the phenomenon The Room, by Tommy Wiseau, let me explain to you its cinematic importance. Wiseau, writer, producer, director, and star of his own great tome, opens his chef-d’oeuvre with loomingly epic ’90s synth-rock, festooned with Baroque flourishes. The camera pans from a pale blue sky to the Golden Gate Bridge, coming in over San Francisco, majestically, insinuating that you are about to be privy to a story. More than a story, a fable. We see a flash of the hero as he rides by, dressed all in black, on a streetcar. In the next cut, we are in the living room of the hero. As he enters, he greets his fiancée, Lisa, with an obtuse, “Hi BABE.” He gives her a newly purchased red dress. He tells her how “sexy she looks.” Then, a young college boy comes into the room. Johnny (Wiseau) spurts an equally obtuse, “Oh, hey Denny” at him, and we are off into the world of The Room.

Wiseau is either the world’s biggest fool, or a visionary—either way, he has produced something magnificent. This film, a romantic tragedy of friendship, betrayal and death, somehow manages to disrupt the normal sympathetic response of the viewer, thereby negating the expected, and producing hilarity. Wiseau’s use of symbolism is cliché to the point of gaudy greatness: red dress, de-petaled roses, over-played soft-core porn scenes that showcase some globular silicone lumps and Wiseau’s own pert butt cheeks. All these “tools” of various stylistic origins are brought together in an asinine but somehow endearing and confounding mash-up. Wiseau’s character, Johnny, seems to be a tabula rasa himself, presented as a foreigner with no discernible roots, who seeks to mimic his surrounding culture. This is made explicit in his dialogic style: parced phrases, spoken disjointedly as if they were remembered from some TV sit-com’s colloquial banter. Johnny is a socially alienated individual, which echoes how the film feels: like it is painfully distant from the viewer.

Through the course of this film, Johnny’s fiancée hooks up with his best friend, goes crazy, and fakes a pregnancy. His best friend deserts him, starts smoking pot and almost shoves a minor character off the roof of a building. The young college boy gets caught up with a drug dealer, and confesses his sexual love for the mother-like figure of Lisa. At the end of it all, Johnny blows his brains out the back of his skull due to Lisa’s erratic, manipulative and abusive love. With so much action, it is hard to imagine not getting caught up in the story.

This reviewer cannot help but notice that all these tired themes seem to be placed next to each other like an assemblage. It almost seems that Wiseau substituted the representations of the representations of emotions, actions, etc. for primary portrayals of them. This is both what causes verisimilitude to fail, and what makes the film a visionary comedic masterpiece. Simply put, this is a horribly made film but

a fantastic artifact.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly squints its way into your heart

Sergio Leone’s 1966 The Good, the Bad and Ugly is the last installment of the epic Dollars Trilogy. Leone’s final chapter is assuredly the most successful of the Spaghetti Western genre. Shot in Spain, this film treats with both reverence and a most potent sort of parody (or even caricature) the quintessential American Western. The film incorporates slap-stick humor, exaggerated—if not cartoon-like—violence, and some of the best one-word lines, delivered by the strapping young Squint Eastwood.

Eastwood stars as the Good (aka Blondie, aka The Man With No Name), alongside a shifty smooth-talking Lee Van Cleef as the Bad (aka Angel Eyes) and Eli Wallach as the Ugly (aka Tuco, aka Benedicto Pacifico Juan Maria Ramirez). Tuco and Blondie have established a mutually beneficial partnership, through which they come to depend on one another like the Wiley Coyote and the Road Runner. The consistency with which they maim, torture, and nearly murder one another, is the routine of their high desert matrimony. Anvils aside, the two become involved in a violent sort of brinksmanship, in which fortunes, luck, and the upper hand change possession as quickly as Blondie can light up his trademark cigar and squint into the oppressive sun—a move that says more than any line in the script, and can melt the heart of even the most hardened graduate student. (The squint heard cross the world, one might say.)

The Good and the Ugly form a camaraderie of mutual assured destruction and affection (despite being brazen, cocksure loners) in a hunt for hidden gold, of course. Blondie and Tuco wind their way through a nightmarish vision of the Civil War era West and encounter the heartless mercenary Angel Eyes (the Bad), who proves to be a good match for the skilled, yet hapless pair. At one point they even inadvertently pledge allegiance to General Lee when they mistake an oncoming company of Union men in desert encrusted Union Blue, as Rebs. This misstep places them in the sadistic hands of the Bad who poses as a Union General in order to shake down POWs and generally beat the crap out of people.

The futility of lost causes, arbitrary justice in the western wilds, and scads of obviously Italian extras in uniform (the Union Army never looked so Italian!) punctuate their journey toward the treasure of colossal proportions. Speaking of colossal, the final duel is among the longest and, dare I say, best of the Western genre. This film is at once gorgeous, hilarious, silly, sincere, and poignant—as well as boasting the pinnacle of 60s pulp and pop in its score and opening credits. The poetics and jocularity of the homosocial bond struck by hardship, the desire for autonomy or wealth, and a constant race against one’s own past and identity (and everything else I’ve mentioned) render this film a masterpiece.