Taking it to the streets

Despite the fact that art and politics have historically been intertwined – think Daumier’s persuasive political caricatures, and Jacques-Louis David’s instrumental role in the French Revolution, for example – it is hard to see nowadays just where art functions in the political process. While sardonic and damning political critique in contemporary art is pervasive, and direct commentary on the current candidates and system has become par for the course, art (in the stricter sense of the word) sometimes seems to be speaking from outside the political arena, preaching to the converted, and therefore unable to participate effectively.

However, the current wave of street art interventions, particularly in support of the Obama campaign, is reinserting art’s presence into the political sphere. Shepard Fairey’s now ubiquitous red, beige and blue silkscreen posters of a solemn, yet dreamy-eyed Barack Obama gazing off into the future, have become a hallmark of this presidential race. Beyond the many forms of election paraphernalia it now appears on (t-shirts, buttons, etc.), Fairey’s design has resulted in imitations, parodies and attacks. From Baxter Orr’s reddish-brown offensive re-imagination of the image to read “DOPE” instead of “HOPE”, to the anti-McCain “FEAR” adaptations and the Hillary Clinton spin-offs, his design has managed to enter into and alter the political rhetoric.

As only a part of a greater movement, which includes such notables as curator Nancy Spector, musician Moby, and artist Ross Bleckner, who were instrumental in the exhibition and art contest Manifest Hope that coincided with the DNC in Denver last month, Fairey represents a resurgence of our culture’s investment in (or at least awareness of) the power images have to inspire and inform the public’s consciousness.

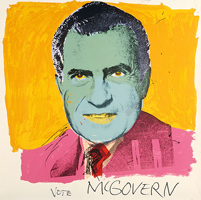

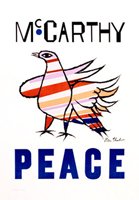

Although it is reminiscent of political posters designed by artists in the past that abandoned conventional campaign advertising compositions in favor of more rousing imagery (could you get more redundant than another poster of a candidate in front of a flag or with an eagle in the background?), Fairey’s design is actually much more conservative than many people realize. As Steven Heller points out in his New York Times column, when compared to Ben Shahn’s pro-McCarthy poster of 1968 or Warhol’s “Vote McGovern” silkscreen of a green-faced Richard Nixon, Fairey’s red, white and blue, Social Realist inspired designs mimic the layout of the prototypical campaign poster and seem to be something of a throwback, rooting Obama’s rhetoric about change and the future in a tradition drawn from the past.

In addition to Fairey, other street artists, such as SAIC alum Ray Noland (a.k.a. CRO), have covertly been plastering the walls of cities across the country with images that range from conventional stencil-like portraits to slogans and more radical designs. While the Obama campaign only officially endorses a few designs (including Fairey’s “HOPE”, “PROGRESS” and “CHANGE” trio), which tend to remain relatively traditional, they have purchased one of Noland’s unorthodox designs to promote a rally in New York City. While not as extreme as his “The Dream” (which has been nicknamed the “Obama-as-Messiah poster,” due to its golden hues and the radiating halo behind his head) or his “Obamahood” poster depicting the senator as a latter-day Robin Hood bestowing health care upon the nation, it certainly is an unexpected image in its less-than-serious appearance and message, as well as its near divergence from the anticipated patriotic color scheme.

While “Obama Art” as a whole may not be quite as avant-garde as one might hope political art to be – in that it is both rooted in advertising or graphic arts and aligned with a party line and a candidate – the Situationist-like intervention techniques of many of its producers, and its break with conventional aesthetics, while managing to engage with a mainstream (liberal?) audience, is at least encouraging to artists who really want their art to make a difference in society.