Of cafes and dancers

by Mark Krisco

Returning to school this fall, you may have looked up and over at The Art Institute of Chicago’s front facade and noticed that instead of the usual three exhibition banners there is one three-sectioned banner advertising a single exhibition: Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre. On some mornings, you might have noticed a long line of people stretching north on Michigan and east on Monroe or perhaps seen television, radio and newspaper reviews and advertisements for this exhibition. These phenomena certainly beg the question, “Does this exhibition live up to the hype?” The answer is most assuredly a resounding “yes.”

The layout of the exhibition space is broken into small corridors. These become alleyways opening onto larger spaces that allow the viewer the experience of a Montmartre local making his or her rounds to various cafes, cabarets, bars and brothels. The cool and nocturnal colors and lighting of these galleries add to this effect.But more important than form is the content of the exhibition, brilliant in its breadth. For this exhibition is not that predictable Art Institute formula of a single Post-Impressionist (or Impressionist), but the recreation of an entire milieu, embodying Montmartre’s famous places and infamous people. The Art Institute recently tried such an approach in their “Manet and the Sea” exhibition without success.

No matter how eloquent Manet’s pictures, he was aesthetically and artistically upstaged by many of the other artists in this exhibition, especially Whistler and Morisot. In Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre, Lautrec is the star and focus of this exhibition except for two instances that I will later point out.

One enters the foyer of the exhibition amid crowds—literally, by fellow exhibition viewers and visually, by Moulin Rouge patrons seen in flanking interior photographs. From here you enter and see, on your left, five photographs of Toulouse-Lautrec and one caricature of him by Charles Lucien Leandre that make clear Lautrec’s personality—that of a sexually and culturally cross-dressing clown with an unerring sense of the importance of public persona. This is then painterly manifested in Lautrec’s retake of himself, pissing in Puvis de Chavannes “Sacred Grove: Beloved of the Arts and Muses” (1884-1889). Puvis’ flying angel as painted by Lautrec now carries a tube of paint, and one gets a clear sense that Lautrec designed in a new order, one that would address and define modern life.

Leaving this room you briefly pass through a small room of posters depicting pedestrians dominated by Steinlen’s formidable “La Rue” (1896) to come face to face in the next room with a mural-sized black and white photograph of the Moulin Rouge’s front facade and namesake: a red windmill.

This room has a surprising selection of artists, many of which are generally unacknowledged. Ramon Casas is one, represented by his more realistic depiction of “The Sacre Coeur, Montmartre” (1890), which orchestrates a wonderful play of dusty rose and tart green tints amid a generally warm blue-grey tonality. The color highlight of this composition is the orange square in the center. Overall, this delightfully fresh painting lends its soft brilliant light to the room with such quiet force that it is hard to imagine this room without the presence of the Casas.

This is, in fact, precisely what is so brilliant about this exhibit: a balance is always kept between Lautrec’s more strident works and those by more “pedestrian” artists, such as Casas, Eero Jarnefelt and Santiago Ruisinol.

Certainly the Art Institute’s Van Gogh depicting “The Terrace and Observation Deck at the Moulin de Blute Fin in Montmartre” (1886) is a truly great work that can stand against any: first, for its play of complementary blue and orange and, secondly, for its poignant expression of Van Gogh’s loneliness. You are led into the work by two pairs of lampposts and then spot, on the observation deck, two standing couples while below them is a seated faceless single figure.

Although this room is dominated by Adolph Leon Willette’s fantastical mural on canvas, “Parce Domine” (1884)—depicting the primary people and haunts of Montmartre—it is Lautrec’s early painting, “Ballet Dancers” (1885-1886), that catches your attention. This is primarily because of Lautrec’s adept usage of the compositional cropping techniques of Degas, Lautrec’s idol at the time. Degas in turn borrowed such novel techniques from the Japanese and was one of the first to do so.

The next room, “Monmartre Places and People”, conveys Lautrec as a young artist searching for his place amid Monmartre’s artistic scene. This room starts with Lautrec hitting a bull’s-eye in the pastel portrait of his friend Vincent Van Gogh. This pastel amply demonstrates that Lautrec’s approach possessed a mature individuality at an early date, 1887. It is a masterwork that stands up beautifully against all the other artists and pictures seen in the room: Manet’s delectable “Plum Brandy” (1877), Van Gogh’s “Agostina Segatori at the Cafe du Tambourin” (1887), and Degas’s “Woman Brushing Her Hair” (1884), which are paired with similar paintings by Lautrec.

On the far wall is a wonderful selection of Lautrec’s portraits. The best of these, the photographer Paul Sescau standing in Lautrec’s studio, illustrates Lautrec’s early pursuit of Japanese aesthetic. This painting is in the kakemono (i.e. exceedingly vertical) format. Lautrec’s addition of three strips of paper to extend the vertical dimension of this work speaks of his embrace of this Eastern format and aesthetic. There is an example of just such a Japanese work directly behind Sescau, which verifies Lautrec’s collections and awareness of Japanese aesthetics.

The next section, “Advertising Montmartre,” conveys in a concise way that Lautrec had a formidable rival in Jules Cheret, who was considered the leading poster artist in Paris and who would be considered the father of modern advertising. However, Lautrec was quick to spot Cheret’s Achilles heel: his predictable, wispy women. Lautrec used this observation to fire back in his Moulin Rouge poster. It was a work that advertised the Moulin Rouge as the luxuriously seedy place that it actually was. Large in scale and broad in technique—especially in its masterful Japonist approach—this image announced Lautrec’s genius to the world and established Lautrec as the most masterful and avant-garde poster artist in fin de siècle Paris.

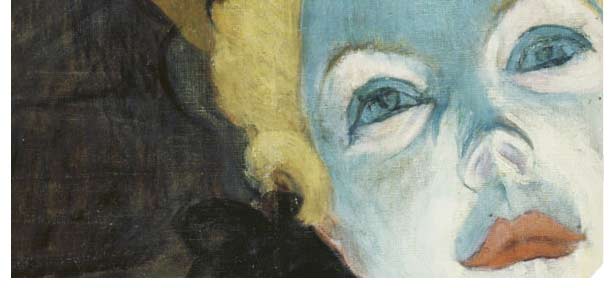

The next room, dominated with the Art Institute’s “At the Moulin Rouge” (1892-95), suggests just how expressionistic and theatrical Lautrec had become. Surely Lautrec’s repeated use of a bright, sickly green was a major influence for the German Expressionists in the early twentieth century.

Then one encounters the first place where Lautrec is upstaged by an unlikely candidate: Edouard Vuillard. Vuillard’s painting “Paul’s Sin” is a work that frees him from the conception that he was a painter of small, “homey” pictures. “Paul’s Sin” was composed on large physical and psychological scales. The seductress’ deceptive candy red smile, accompanied by her lecherous and leaning arabesque, fully suggest that like the dark red wine on the table she shall indeed tarnish the delicate white flowers of “Paul’s” formerly civilized behavior.

The room that follows has little to do with Lautrec but everything to do with Montmartre. Documenting the “Chat Noir” cafe and its shadow puppet theater, the space features the artist Theophile Alexandre Steinlen. His paintings, particularly his mural “Apotheosis of Cats” (1897), make one realize that we today (of the Broadway musical “Cats” generation) are not unique in our fascination with this emotionally illusive and primarily nocturnal creature.

The next room features the Montmartre celebrity Aristide Bruant, followed by the Cafe’s concert room. These two rooms set a cadence that remains intact for the remainder of the exhibition: one where Lautrec repeatedly rises above as the true star. While little has been made of La Goulue’s personality as a major Moulin Rouge presence—she did have to be ordered to pose for Lautrec—other rooms are given to each of the Montmartre personalities: Lautrec repeatedly depicted Aristide Bruant, Yvette Guillbert, Jane Avril, Loie Fuller and Marcelle Lender.

The result of this string of galleries makes abundantly clear how it was Lautrec—not these performers—that primarily created the mythic proportions that these flash-in-the-pan Montmartre performers now have. In this way, Lautrec can be compared to Andy Warhol in our day. Of these “entertainer” rooms the very best is that of Loie Fuller. The organizers of this exhibition did a great service by rematting and reframing all but one of the fourteen one-of a-kind Loie Fuller prints.

In the “Maison Close” room Lautrec is again temporarily upstaged, this time by Degas, whose sparsely colored, small monotypes are brilliant and sexually frank portrayals of humanity. Lautrec’s paintings in this room, except for the humorous “The Laundryman” (1899), simply do not measure up to Degas’. In this room one begins to feel the waning of Lautrec’s abilities and energy.

In the next room, however, he produces a brilliant portfolio titled “Elles.” This portfolio, like the Japanese printmaker Utamaro’s “Green House,” depicts the daily life of prostitutes in a series of twelve prints. Lautrec’s portrayals of these prostitutes have an intimacy that conveys a less idealized image than his Japanese source and predecessor.

The penultimate room is brightly lit, and predominantly displays Lautrec’s late circus-themed drawings. While these drawings may have proved Lautrec’s sanity—their true motivation—they do not compete with his early primary circus painting, “Equestrienne” (At the Cirque Fernando)”(1887-1888).

Lautrec’s large painting sweeps the viewer into the arena to reveal the tensions between the whip-cracking ringmaster Master Loyal and the female circus rider, modeled by Lautrec’s mistress at the time, Suzanne Valadon. Lautrec adds comic relief with a clown on the left border. Lautrec’s circus painting seems to speak of a series of tense and comic moments.The last room of the exhibition contains a single Lautrec painting, the cynical “At the Rat Mort,” and a wall with two early Picassos: a drawing and watercolor promoting the “Jardin de Paris” and the oil “The Blue Room.” Lautrec’s poster of “May Milton” is seen in Picasso’s oil.

In summary, one leaves this exhibition with a sense of Lautrec’s genius and of his influence on the artists of his and our day. This is Lautrec’s formidable achievement and is all the more amazing given the biographical facts that suggest Lautrec’s brilliant light was the result of burning the candle of his life at both ends.

This exhibition closes on October 10th, and it is strongly suggested that you make the effort to attend this very special exhibition for its layered approach, sensitive handling, and breadth of content. You are sure to be rewarded and inspired to return again and again. Toulouse-Lautrec and Montmartre is indeed something rarely seen today: a public blockbuster that has much to teach even the most artistically learned visitor.

October 2005