Youth art in the new millennium

Story by Amber Smock

If you were a creatively talented teenager in the Renaissance, the first step to becoming a successful artist was to serve as an apprentice to a master artist. Michelangelo Buonarroti, at the age of thirteen, obtained an apprenticeship with the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio. At fifteen, Leonardo da Vinci became an apprentice to Andrea del Verrochio.

Today, many young artists are still serious about art, but today’s framework for youth art is shaped largely by our laws and social values. We now have child labor laws, public school systems and social beliefs that value childhood. Yet as kids get older, they leave behind the colorful classrooms of elementary school for the more “serious” environments of junior high and high school. Whether they pursue their artistic inclinations or not depends on a number of factors.

As SAIC Arts Education professor Drea Howenstein points out, art education models vary wildly from school to school, from community organization to community organization. Teachers help students realize their artistic potential at the individual level. Jorge Lucero, a SAIC alum who teaches art at Northside College Prep, points out that “high school art needs to stop being an intermediary between being a student and becoming a ‘real’ artist. Learning skills and finding a voice can coexist and don’t have to follow each other.”

In Chicago, as in other major cities, it hurts to consider the sheer volume of issues schools must negotiate: neighborhood isolation, the need for diversity sensitivity, teacher burnout, student dropout, immigrant/refugee adjustment, teen health, gangs, drugs, and more. Still, many Chicago youth who want to make art do make it, do find art mentors, and do go on to college to study an art-related field. As well, many young people who usually wouldn’t think twice about art are getting a chance to open their minds.

Magnet schools

As one option, Chicago offers magnet schools for students interested in “majoring” in a particular course of study, such as art. Students must apply and be accepted to enroll. They come from all over the city. Lane Tech High School, a magnet school and one of the largest Chicago schools with an enrollment of nearly five thousand, offers the most extensive arts-focused curriculum in the Chicago Public School District.

At Lane Tech, the art department has seven art teachers and architecture classes taught through the technology department. The classes taught include painting, photography, computer design, and graphic design. Amy Moore, Lane Tech’s ceramics teacher, acknowledges that working in the public schools can be “enormously difficult.” Regardless, she adds, “Art is a subject that is highly regarded and supported by administration and staff, which makes the art teachers and students very happy.”

Magnet schools that focus on other subjects can still offer excellent arts opportunities. For the past four years, Jorge Lucero has taught art at the selective Northside College Prep, which focuses on tech skills. Lucero and his colleagues offer students the opportunity to investigate art as an alternative path. As a result, Northside Prep students often take up to four art classes a year. The school also offers a senior project program that allows students to develop a full-year art project under the guidance of a mentor. Lucero currently mentors a poet and a sculptor.

The Northside Prep art department also extends its offerings by collaborating with community arts organizations such as Chicago Arts Partnership in Education (CAPE), Transcultural Exchange and Performing Arts Chicago, through whom the school has formed an ongoing partnership with the performance groups Goat Island and Lucky Pierre. In addition, Northside offers after school art clubs, so kids can spend even more time being creative than their peers at other schools.Public schools

For students who don’t attend a magnet school, what sorts of arts opportunities can they expect? While there are 83 high schools in the district, take a look at, for example, Amundsen High School in Andersonville. Its Chicago Public Schools profile notes that as of 2003, Amundsen enrolls about 1,500 students, 90.4 percent of whom come from low-income families. Teacher Janet Fennerty notes that its most recent rate of graduation is 51 percent. The majority of the students live in areas outside of the gentrifying Andersonville neighborhood, and Amundsen has an active gang presence.

Students speak over 40 languages, with 18.6 percent having been identified as having limited English skills. To better serve the diverse educational needs of the students, seven years ago Fennerty helped start Global Village, a school-within-the-school. Incoming freshmen are selected randomly for Global Village classes, whose teachers work together to integrate the curriculum. Students stay together through each grade, providing a better opportunity to know one another and learn to break cultural barriers. The administration has lately dispersed Global Village juniors and seniors through regular classes, somewhat dissipating the original full integration. Still, 62 percent of Global Village students graduate.

Global Village students work on art projects for 45 minutes a day, and community partnerships, as at Northside, boost their range of artistic opportunity. Once a week, Drea Howenstein brings in her art education students from SAIC, who develop ongoing projects with the kids. Last semester, they worked on an environmental/art project called “I Am Nature,” which culminated in a show at 1926 N. Halsted. This semester, they’re focusing on the theme “I Am,”which lets the high school students tell about their families and cultures. “I Am” is opening at the Hot House gallery on April 30.

Though Fennerty notes that a few Global Village students have taken art very seriously, going on to pursue art-related majors at college, but for the majority of the students art is just part of school. Or is it? Art lets kids share their uniqueness, their emotions, and their sensitivity to the world around them.

Nationwide, opportunities for kids in the arts are particularly uneven. President Bush’s No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 promises money for arts education as a “core academic subject,” but the arts haven’t seen any funds. Instead, the Act’s most striking effect has been to create public school environments where every step a teacher takes is made with the standardized “ability” tests in mind. Integrating the arts into the classroom is still desirable, still mandated, but teachers’ necessary freedom of mind is being slowly throttled.

Community organizations

Besides working at Lane Tech, Amy Moore also teaches at Marwen, an exceptional community organization in River North that provides free art classes to underserved Chicago youth, grades 6-12. At Marwen, all supplies are free. There is a library, a career center, spacious studios, and when you enter the main lobby, you’ll find yourself in a warehouse-style gallery as hip as any big-name gallery in the area. Students can take up to two classes a semester, classes being on average two hours long.

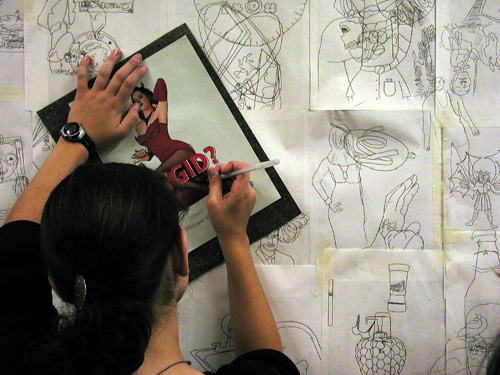

Students who go to Marwen have a strong interest in becoming artists, and Marwen caters to their seriousness by providing career advice, school trips, and even a career development class. Classes are taught primarily by professional visual artists, who tend to set high standards in the classes. Though serious, within the studios, the kids are free to experiment along with other experimental artists.

This past winter semester, Moore taught “3-D Me,” a ceramics class that taught students to make life-sized busts of themselves. Other classes offered included Maria Gaspar’s “Art in a Box,” Benjamin Jaffe’s “Digital Developing” and Darrell K. Roberts’ “Drawing Studio.” Guillermo Delgado taught “The Human Form: Advanced Mixed Media,” a figure-drawing class concentrating on the nude human form, which requires parental permission.

The winter semester classes held the opening of their art exhibit at the beginning of April, and the most captivating sight, beyond the school-open-house/professional-art-opening mood, was to see the moments when students would drag a parent up to a painting or drawing or sculpture, only to say, “That’s mine!” at which the parent would whip out a camera, or smile with only half-hidden pride.

Delgado, the figure drawing teacher, kept arranging students in front of their drawing for photographs. He explained later that the students in his class arrive “hungry for an intense experience,” which he tries to provide through the figure drawing sessions. Besides helping them to build their portfolio, Delgado believes teaching figure drawing helps the kids learn respect for the human body. It’s hard to imagine a class like this getting a green flag in the public schools.

Cyd Engel, Marwen’s Director of Education, points out that Chicago community art organizations do not face the same stress of testing standards that public school teachers face. Marwen serves kids from 58 zip codes and is much more like a school than an after-school group. It also offers professional development art classes to teachers, for a fee.

Eighty-five percent of Marwen students go on to college, many to art schools like SAIC and the Rhode Island School of Design. Many go to UIC. Alumni often continue to be involved at Marwen, which offers many their first opportunities for a one-man show. The same night as the winter semester opening, a group of alumni held a show on the second floor of works two feet by two feet in size.

Throughout Chicago, other organizations also serve the needs of youth artists: from Street-Level Youth Media in the Ukrainian Village to Little Black Pearl on the South Side, from umbrella organizations like Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education to institutions like the Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum. Art opportunities in Chicago communities have vastly improved over the years, according to Delgado, but the thing with young artists is there’s a new crop every year, which means new connections to be made.

Art educators

Art educators, as mentioned, come in many stripes. Marcy Sperry, a graduate student in the Art Education department at SAIC, points out that many art ed students want to teach in community organizations or museums or alternative education settings, not just schools. In addition, many of the art teachers now involved in art education never thought they would be teachers. For most, it’s a matter of connecting with and helping people.

For instance, Amy Moore says, “Did I always want to be an art teacher? No way! Teaching to me is more important than art in the sense that I would rather teach math than work at an art gallery.” Jorge Lucero of Northside Prep remarks, “I never intended to be a teacher but the meaning of my name, which is the Spanish version of the English George, is farmer, one who plants seeds.”

For some, it’s about community: Delgado says that as a kid, he constantly looked for ways to bring people together. At one point he wanted to be a magician; at another, he wanted to be a priest. Today he is neither, but when a teacher first asked him to come to speak in front of a classroom about his art, he discovered that he loved bringing art into kids’ lives.

With so many opportunities, it’s tempting to streamline them into a single art standard for everyone, but this would cause the youth art scene to lose some of its vitality. The urban landscape creates so many school situations, and there are so many students, that the very diversity is a strength. Plus, there will always be students who don’t want to make art, and there will be students who really, really, really want to.

Even back when Michelangelo at thirteen signed up as Ghirlandaio’s apprentice, he did it because he really wanted to: he defied his father, who was horrified. And yet he was, even then, a great artist. Today, art opportunities for young people are multiplying, and still making art is just about making art. It’s about the individual. Five hundred years after Buonarroti senior tried to stop his son from learning more about art, art classes thrive, even on budgets of zero, even in the worst neighborhoods. Through art and the people who teach art, young people continue to leap barriers: cultural, educational, and personal.

For further information, please visit:

The Chicago Public Schools website at www.cps.k12.il.us/.

Jorge Luceroís Northside College Prep website through www.northsideprep.org.

Marwen at http://www.marwen.org.

The City of Chicago’s Gallery 37 at www.gallery37.org.

A particularly good site to learn more about arts education in Chicago is the Chicago Arts Partnerships in Education at www.capeweb.org. Visit its links page to find like-minded organizations.

Remember back in junior high and high school when you were just a kid who liked art? How often did you get to make art in school? Did you know any other young artists? Did you know any adults who made art for a living?

Lots of young people take art seriously, but very few opportunities exist to participate in an art community that extends beyond the boundary of school. For many, college is their first chance to be part of a community making art. Yet if a young person has talent, why shouldn’t he or she develop it right now?

Part of being an artist, particularly at SAIC, is helping to revitalize the art community. That includes reaching out to young artists in the schools. Every day, dozens of SAIC students, faculty and alumni work with young people in art classes and workshops all over the city and beyond.

As part of our own commitment to the art community, F News is proud to announce the development of Fzine.com, our new online division devoted to covering news about young artists and their teachers. We will be featuring profiles of youth artists and the people who work with them, as well as offering career advice, art resources, a calendar and an art gallery.

Fzine.com’s main goal is to serve as a news site where any young artist from any school and any walk of life can see what other artists their age are doing. In addition, Fzine.com will offer perspectives on what it is like to study for an art degree and go on to work in an art-related career. In addition, art teachers will be able to use Fzine.com to network and evaluate practices in other schools.

When you visit F News this spring at www.fnewsmagazine, take a moment to check out Fzine.com, www.fzine.com, to see how we’re coming along.

Freelancers, please note: Fzine.com desperately needs writers, artists and computer wizards who would be interested in helping to develop this website, particularly over the summer. If you would like to learn more, or you know someone who works with youth artists, please contact Amber Smock at [email protected].