Image courtesy of Microcosm Publishing.

If you’ve ever purchased clothing from shops like H&M, Uniqlo, Old Navy, or Forever 21, you’ve purchased fast fashion. It can be hard to resist: Who doesn’t like a $10 logo tee, a $40 pleather jacket, or a pair of $35 jeans at half-price?

The answer? The millions of people — women, mostly — who live in various states of servitude in order to provide this clothing to consumers in wealthy countries like the United States.

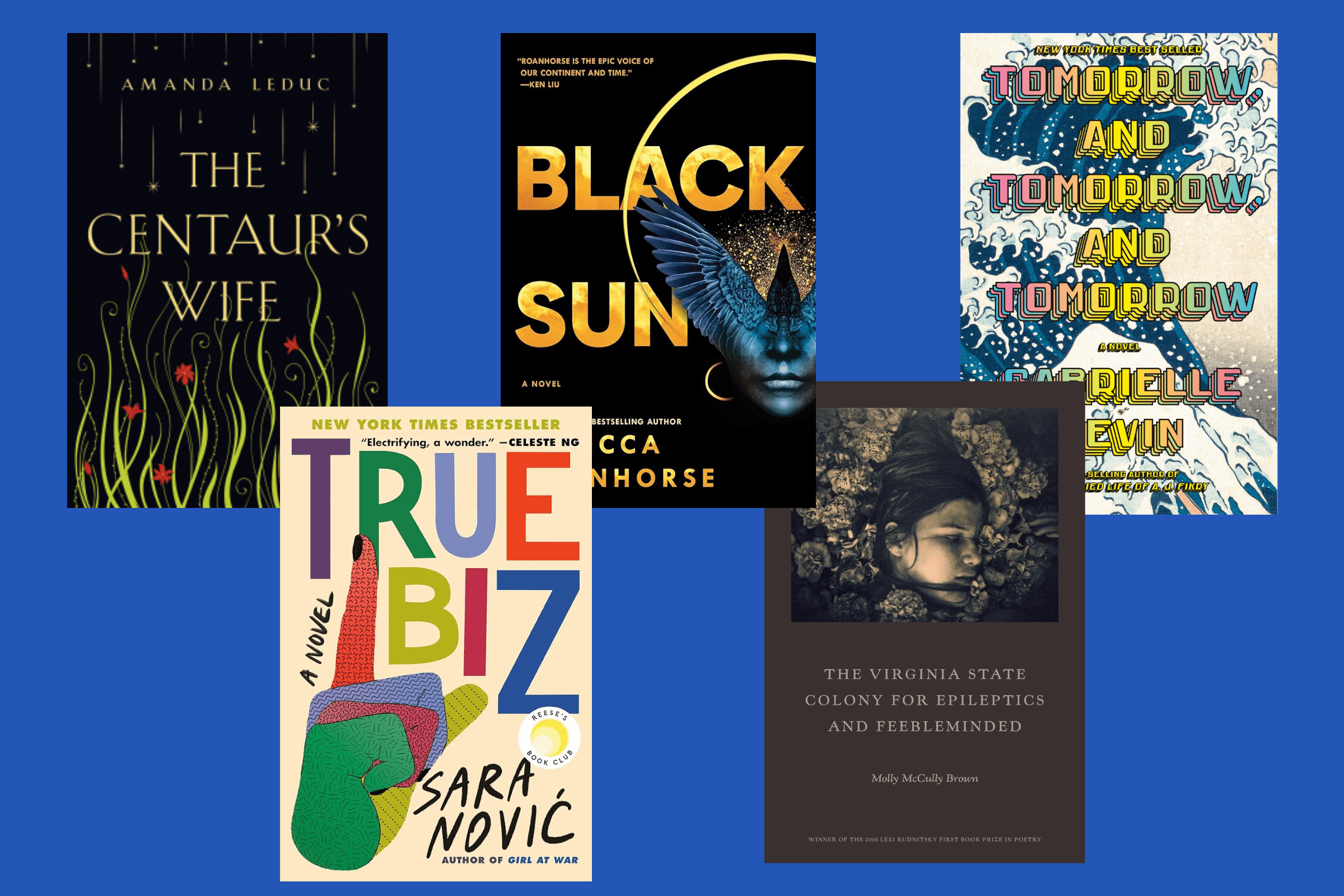

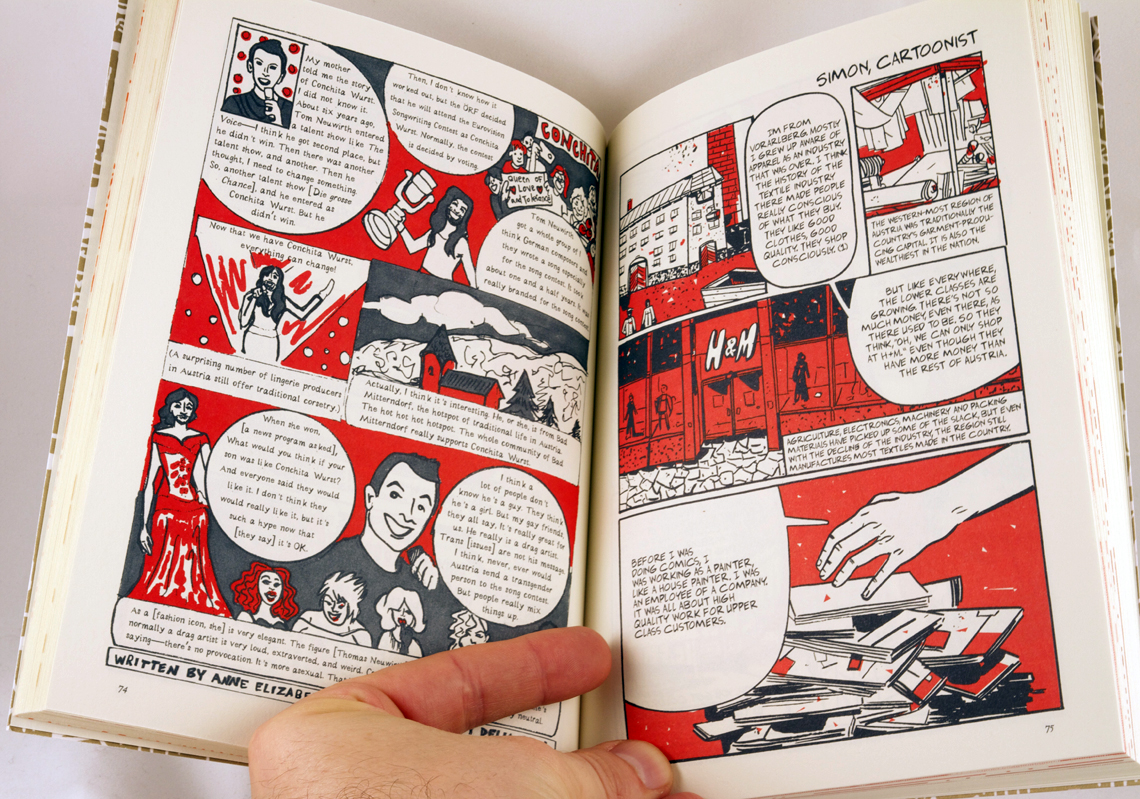

Award-winning journalist and cultural critic Anne Elizabeth Moore’s essential comics report, “Threadbare: Clothes, Sex, and Trafficking” (Microcosm Publishing, 2016), is a thorough and alarming investigation into the various ways fast fashion keeps women worldwide in vicious cycles of destitution and oppression. If you’ve got questions about what fast fashion is and what it’s got to do with you, the dozens of comic narratives in “Threadbare” will provide a sobering education.

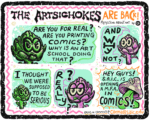

Fast fashion, according to Moore’s definition, “is named for and based on the concept of fast food … [and] has sought to make stylish but affordable clothing available to the consumer.” Moore and her collaborators — Moore’s journalism is rendered in illustration by six different members of comics collective Ladydrawers — use “Threadbare” as a way to explore the ethical cost of this “affordability.” Their view is global: Each chapter of the book focuses on a different part of the world as it relates to the fast fashion market and, as the title suggests, the sex trafficking trade.

For as we learn in “Threadbare,” the two markets are inextricably linked — if you’re on the production end of the $1.2 trillion dollar global fast fashion spectrum, that is. Many women in developing countries feel forced to work in sweatshops, for example, to avoid prostitution in order to feed their families; however, when there are no vacancies, when factories literally collapse, or when a woman’s health cannot tolerate the conditions of the shops, she may turn to sex trafficking as a viable, often highly preferable alternative. When missionaries and NGOs muscle their way into these parts of our globalized world to “help” women out of the sex trade, they often “help” them right back into the slave wages and illness of the fast fashion production line.

The comics in “Threadbare” are rendered with care and the artists must be commended for clear, concise handling of such an extraordinary amount of information. Each chapter has its own, pages-long endnotes section where Moore dutifully cites her sources.

But, as other reviewers have pointed out, much of the book suffers from what feels like a formatting (or printing?) blunder: Some of the comics’ text, such as Chapter 3’s “It’s The Money, Honey,” illustrated by Ellen Linder, is so incredibly small, this reader suffered strained eyes and an actual headache while trying to make out the words. The recommendation of reading “Threadbare” with a magnifying glass nearby is not made ironically.

Moore — who recently moved to Detroit as part of the Write House program but continues to advise students in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Low-Residency program — is a tireless investigator but approaches her subject with great compassion for the individuals under her lens.

“Threadbare” is a grueling journey of facts and figures; were it not for the personal stories offered in each chapter, the book would be far too easy to skim. Whether we’re in the United States, meeting retail workers or sex work advocates, or Austria, where textile producers and tailors have practically vanished into thin air, it’s the people profiled by Moore and drawn by the artists that make the book uncomfortably unforgettable.