John Coltrane’s sweet sounds swirl around the space.

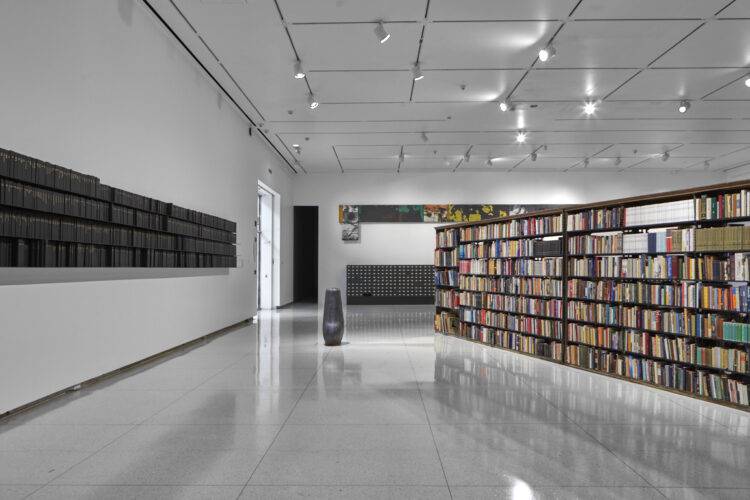

There is something precious about this moment, my eyes closed, in front of a sound system with a vinyl record rotating on a turntable. When my eyes open, there are nothing but African artifacts piled from the floor to the ceiling. Hundreds of objects, piled high, a dense forestry of material obstruction. Together, the music and the works make up “African Still Life #3: A Tribute to Patric McCoy and Marva Jolly,” a double feature of acquired collections that spills out from the exhibition’s two assigned rooms into the museum’s lobby.

What connects this grouping? Probably nothing. Presumably something. Perhaps everything. For any artist, the prompting question would be credible, if not downright necessary, but for a multihyphenate creator like Theaster Gates, known for his artistic chicanery, it’s unnecessary. In Gates’s work, stylistic conundrums, performative complexities, and object-based quandaries are a given.

In his complete presentational return to Hyde Park, a neighborhood of unequivocal significance for its role in artist’s notorious “Plate Convergence” at Hyde Park Art Center , “Theaster Gates: Unto Thee” at the Smart Museum of Art marks Gates’s first solo museum show in Chicago. For those familiar with Gates, the exhibition is as on-brand as ever, a congratulatory marker to his well-lauded status as an activator of the archive. Above all else, this is what Gates has become known for, accruing titles like steward, collector, protector, caretaker, and the artist’s own self-designation as a “keeper of objects.” In fact, it now seems almost impossible to make your way through Gates without first discussing or prompting imagery that beckons forth this part of his identity. The exhibition is neither new nor exciting for its continuance of this trend, despite its positioning of notable archives that Gates has come to represent out of his relationship with the University of Chicago. The novelty might then lie in this very fact: a motley collection of recent acquisitions and unique first-time groupings.

However, here is the thing about Gates’s archival posturing, it is often without recourse or scrutiny. Pairings of objects and archives, seemingly unrelated, are left critically unattended, in part, because of Gates’s pursuit to hone a network of social, political, and cultural relations to engender meaning. A penchant for this leaning into a constellation of references remains an aspect equally frustrating as it is imaginative. Instead of relying upon simple singular definitions or objecting to a hazy atmosphere of possibilities, Gates welcomes in a density of complexity at every turn. Complicating the archive further, Gates’s authorial prescription of meaning and value, accrued through artist talks, interviews, and written statements within exhibition catalogs, produces a labyrinth of interpretation. Meaning and value in Gates’s archival practice, therefore, are continuously reordered and renegotiable. But unlike any old labyrinth, the goal here is not simply the opening at the end of the maze but the process of finding a way out.

For an artist dedicated to archival activation, a great disservice is done by not pressing with force into the collections he puts forth. It is not that the work that he does is lackluster or indefensible, but rather that indetermination sweeps across writings about the artist with disappointing fervor. More often than not, one finds an innocuous tendency to speak about the artist and not about the art, leaving to the wayside a systematic or careful approach to Gates’s work itself.

Frequently, scholarship (and here, curation) apprehensively arrives at Gates’s art only to walk around it – bypassing and tiptoeing – and rarely entering into it, crystallizing its complexity further. My point is not to suggest that a level of precision is necessarily absent but rather to insist that it is often misplaced; the gravity of Gates’s stature as an artist, innovator, and creative – his performativity – is inextricably linked to his pieces. Critically interpreting works by Gates thus follows a logic that demands a parsing through not only subjective regard but also authorial intent. So, when archives are pressed together with no maneuverable room, there is inevitably no way out; and, like most living things, breathing is needed, and within the curatorial layout at the Smart Museum, proximity stifles and chokes the life out of Gates’s work. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, for the institution, the lesson to be learned is simple: less is more.

Indeed, Gates’s archival decisions deserve respected consideration and criticism in large part due to their representation and elongation of human life. Gates is at his most dynamic and provocative when objects/archives/works stand out more like an odd exclamation mark at the end of a bewildering turn in a sentence. The artist shines even when perplexity is the only resounding murmur heard at the heart of his art. When delivered correctly, Gates calls forth a plethora of questions that not only adhere to the practice of his projects but also raise topical concerns facing contemporary artists today. While at times these gambits can fail, more often than not they succeed brilliantly.

If testing interpretational parameters is the wellspring of Gates’s practice, then legibility is his gavel. “‘The death of the author’ has meant not ‘the birth of the reader’, as Roland Barthes speculated, so much as the befuddlement of the viewer,” Hal Foster would go on to write in his famous essay, “An Archival Impulse.” Is Gates’s eagerness for topic coverage and seemingly expansive reach in theme, coupled with authorial suggestion, not the heightened version of the authorial absence to which Foster speaks? That is, Gates’s archives fall prey to a far more deleterious aspect of contemporary artistic practice, a desire and suspension of critical determination, a disturbance of authorial voice so absolute that the only thing left standing is the viewer and the deluge of language muttered around us to shepherd us, proverbially, home. Eclipsed by persona and artistic relevance, contemporary art relies on viewer discernment, struggling to solidify its identity. By opening the boundary of interpretative parameters so widely, artists like Gates invite a vacuous space that consumes conclusions and emits apprehension.

Object labels across the exhibition offer an uneasy example and no convenient answer. Strung together, often with multiple paragraphs, the texts position institutional relevance over artistic ingenuity. Explaining the use of Pietra Luna (“moonstone”) granite in the exhibition, one label extols a narrative about the construction of the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, whereupon its completion, Gates received the surplus material. History does not bestow fundamental logic a priori. There is no clear indication why Gates was interested in the material or even its connection to the works around it. In fact, the exhibition utilizes two different forms of labels, one dedicated to descriptive analysis of archival material and another for the works themselves. Compared side by side, the show makes a clear indication which to pay attention to, regardless of its intentionality one way or the other.

In paying homage to the history of the material, one loses sight of Gates’s choices and consequently his purposeful pairings. Archives lust for the potentiality of being fashioned. They ascribe, subvert, remake, order, and enumerate. Kaleidoscopic in use, archives have limitless potential. To prioritize their originating history is to simply incorporate them as they were, and to do so would be perfectly alright. But to do so with Gates would be to fundamentally misunderstand what the artist does and its consequential value.

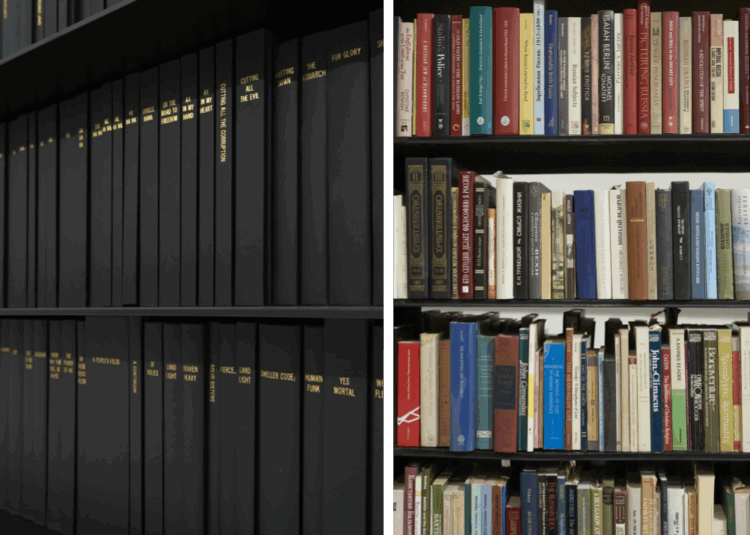

Take, for instance, “Walking Prayer” set against the Robert Bird Archive, a collection of more than 4,500 books from the late professor who taught and was beloved at the University of Chicago. Bound in black cloth, “Walking Prayer” features a swarm of literature on the Black experience, lined on four levels, each with a golden embossed title. Read back to back, the titles form either a succinct stanza, depending on one’s attention, or one long single poem. They can be read right to left, or reversed, making for punchy but nonetheless understandable fragments. It is a kinetic force that stimulates the work. Viewers must move and read for the piece to come to life, a joint effort that needs a catalyst. The presentational installation of Bird’s library is no different. Composed from books and magazines on Russian and Soviet modernism, film, and more, the archive blossoms cathartically in response to visitor engagement. In reading title after title, the experience mirrors that of “Walking Prayer,” and in doing so, opens the space to conceive the conceptual parallax formed between the two works. The similarity drawn between the two, gently indicated in the label text, concretizes through the objects themselves. It is entirely irrelevant whether a visitor elucidates a commonality between, as the label says, “communist ideologies and the Black radical tradition.” What matters, above all else, is that the possibility exists. Placed “Unto Thee,” viewers can scrutinize and then decide for themselves.

A sense of peripheral histories surrounds the exhibition. But for viewers, the continued evocation of histories untethered and unanticipated pervasively troubles the material entities that substantiate their inclusion. While Gates is never championed as the contemporary art world’s most ecologically friendly artist, the shocking misnomer recalls the catchy slogan, “Reduce, Reuse, Recycle,” which aptly describes his material reconfigurations. If the known phrase provides an apt conceptual frame of Gates’s material use, so does its simultaneous extension of embedded histories point to an ethically masterful attention to how histories can continue. Images from the Johnson Publishing Company Archive prolong and old glass lanterns from the University of Chicago’s Department of Art History transition into a digital afterlife in “Art Histories: A Reprise.” Sampled and remixed, these histories undoubtedly seek communicative threads, but a generalized history – a shared lineage to the University of Chicago – used as a blatant defense or justification for inclusion in the show does not grant a work artistic or conceptual carte blanche. Forced similarities are almost always found out to be just what they really are, smoke and mirrors. When there is room – a visual, material, or aesthetic gap just big enough to be formed – be patient. Let the viewer take a leap of faith; Gates does.

For all the meaningful confusion that arises out of Gates’s projects, there is an unparalleled effect that leaves both calamity and clarity. If it is a wondrous performativity of archives and an unwillingness to acquiesce to a final determination you are after, then you will find resonance with Gates. But at the Smart Museum, blink and you will miss it. Such a misstep, however, is easily remedied, for present failures can reflect absent successes. All you have to do is make the connections yourself, even when the institution offers you no help – a belief in the mutable potential of archival objects to be in an evolutionary state awaiting their next assignment. This is exactly what Gates would do.

Caught within the archive’s labyrinth, ascension is the only way out.

Very interesting analysis. Whatever the conclusion, each time I visited the exhibit (3 times!), I felt the weight, the solidity, material reality of it.