“Fur”

There had been rumors of joy; of sugared things and silks; of life and living and those last good things left to us, beyond the village; beyond the forest; somewhere on the edge of everything, and Aster thought every word of it to be true.

But the first ones to go missing were the men. Then the boys.

And the girls and the women were left to themselves. Left to the empty fields and the gravel roads and the sallow shacks of their fading world. The dogs soon vanished; cows, pigs, sheep slaughtered in the night. House sparrows and chapel birds quieted to the whisper of nothing, and not a sound was heard beyond some distant howl or the hollow wind as it ripped through the trees. A woolen silence settled upon their village, and even Aster, despite her plastic hopes, felt the heavy shadow of the inevitable creeping over her.

She was alone, her older sister and her. Their father — who’d been steadfast in his love; his teaching; his service — had disappeared like so many others in the dew of a single night. He’d vanished — bed made, clothes folded tidy and neat on the dresser — and, that morning, the sisters awoke to an achingly quiet house: the only sign of their father’s existence the groan of an open front door.

It was then that the fur came up in the creeks and the rivers, curling in the ripples at the banks, stitching themselves around the reeds in the shore. Thick black fur. Tufts of it. Rolling through the grass; tangled around branches and roots. It swirled out of the woods, tumbling into the village with the grace of so many ghosts.

The first hairs Aster found were laced in the crooked veins of the kitchen table. Then, in her mouth, strung through the gaps between her teeth. Soon she was picking hairs out of the last oatcakes; watching knots of fur roll along the village road; and she pulled more clumps from the garden than any vegetable or weed. It was on her clothes, on her skin, woven here and there into her flesh, and she knew she was breathing it in.

That strands of it were swimming around inside her.

There were even hairs among the bends of her older sister’s body, clusters of it floating past her eyes and landing on her ruddy cheeks. Her sister, Edith, hadn’t moved without the helping hand of another since Aster was born, and so the fur found her like dust on a mantelpiece: clumps of it gathered around her waist and her arms, entwined in the hairs on her shins. As Aster picked her sister’s flesh clean one afternoon, Edith looked at her with a placid smile stretching across her face. “The women and the fur,” she whispered, half-laughing, “All that will remain.”

When the wolves came in droves soon after, trailing out of the woods with sunlight nipping at their heels, Aster and Edith felt rapturous. The creatures seemed to be dusted with sugar, shampooed in gold. Their black fur glistened, and their ruby eyes glowed. Clothed in crisp white dresses, fur teeming around their throats, they moved like gentle-women with the rehearsed delicacy of prey. Their bodies were those of humans: soft-skinned and bare; but their heads were those of wolves: matted fur, pointed ears, sharp teeth, long nose. They trailed past each house in the village, jubilant and joyous, raucous and inviting. They danced and hummed and sang — their howls, once sinister in the distance, now melodic and divine. The sisters saw themselves outlined in the beasts’ existence; witnessed, within their gloved hands, something they’d always craved — and a revived hunger sited within them, one which had never before been sated.

For a moment, the sisters forgot all about their father, lost to the woods; about their mother lost to birth and despair, and they pictured themselves crowned queens of bliss, seated on a throne of fur.

The other women left in the village shuttered their windows and barred their doors. They observed the same hunger in the wolves’ eyes but saw nothing to be shared in it. They whispered to their friends, hid away their pearly daughters, took nails to doorframes, took husbands’ guns for their own, and peeked through the sunken slats of their shacks at what they thought to be their doom. They bided their time. Waited for the beasts to go.

But Aster and Edith had made up their minds. They would not wait to rot away with the others. They would not step willingly into that mouth of traditioned decay. Instead, they followed the procession at a distance, Aster pushing Edith along in her wheelchair. It was a day of walking — of hearing just up ahead the soft-padded feet of the wolves waltzing through the brambles and the branches and the bonesets. At each step, they felt an electricity run through them — a sweet shock that Edith could only recall feeling at the creek when the other village girls her age would gather there in the summer years ago. She remembered watching out of the corner of her eye as they undressed; as each budding limb broke free from the clutches of aprons and men, the sun exalting in their momentary abandon. Edith remembered Mara, the oldest of the girls then, slipping into the water, her body reflected in the creek. O, how she’d longed for her; wanted her. But such things, young Edith knew, could never be.

It was only once the sun had set, the burning light dripping into shadow, that the caravan before them halted, and the sisters saw a stark-gray tower looming up ahead of them. Edith thought wildly of castles and princesses and fairytales she’d been told as a child, colors rushing through her head, dreams twisting into the blunt point of reality. Thoughts of summer, of women and girls, of the men and the boys lost to the forest evaporated from her mind, and all that lingered there was thirst. The wolves — Edith realized now — had noticed her and Aster following them. Had, she thought, known they were there all along, and they welcomed the sisters with the silence of cats and the amiable eyes of kinsfolk.

Edith studied each face as they passed through the pack. Crooked noses and bloodshot eyes, big teeth and lips glistening with spit. The wolves helped them up the stairs of the tower and onto the terrace, guided them into the hall and up another set of stairs that flashed before Edith’s eyes with a luxury fine and blinding. Visions of pink, of taffeta, of marble women, and pillows stuffed and bursting with down played before her like a mirage.

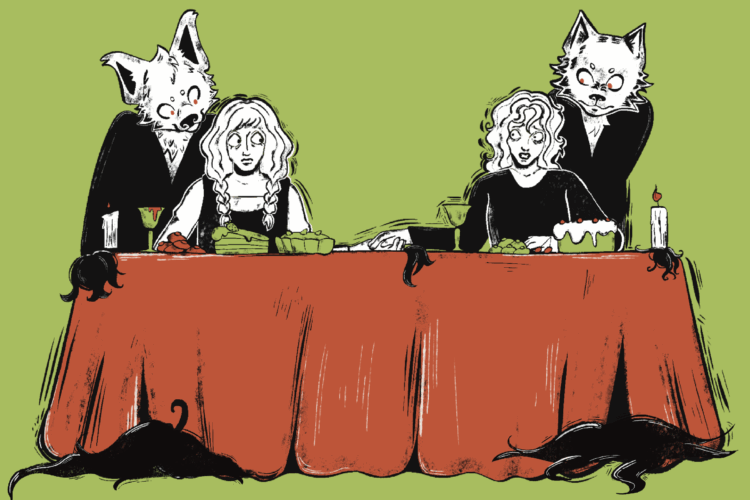

It was through no ability of their own that the sisters found themselves sitting in the grand spoils of the dining hall. The table was long and set with a mountain of tumbling sweets — finger cakes and jelly cookies, fruits and tea, cherries dipped in liqueur with goblets of wine, and chocolate orange tarts that crumbled to pieces. There was fine china, napkins edged with spidery lace, and, all around them, the ruby eyes of the wolves watched each move they made.

It was quiet. The room pounded with a brittle hush. Aster reached for Edith beside her, grasping her hand. Anticipation filled their lungs. The beasts were waiting, but for what Edith feared to know. The hunger inside her ached. She felt it in every muscle, every bone and watched tuffets of fur dance before the flickering candlelight.

It was then the wide, white doors of the kitchen burst open and a succession of covered silver trays was carried out into the dining hall. The wolves-in-waiting were dressed in stiff black coats, and they rushed into the room with the practiced precision of routine; stood by each diner, dish in hand. They placed the covered trays on the table, and Edith saw her reflection in the silver dome, could see the twisted warped finery of the room around her. She thought she saw black hairs beginning to burst from her skin — clumps of it, like the wolves, thick and full — and the hunger banged inside her

With a flourish, the wolves-in-waiting removed the silver cloches, and a triumphant roar started out from the wolves: a delicate, giddy whimper that sprouted into howls and cheers. Edith looked down at her plate and saw the crisp golden head of one of the missing village boys, baked and garnished with frosting, candied strawberries, lemon, and cherries where he’d once had eyes and cheeks. She gazed around the room and then at her sister beside her. Aster’s lips were spread into an undeniable grin. Her slim fingers twitched in Edith’s palm, and Edith stared wide-eyed as Aster’s hands urgently skittered to her knife and fork.

Again, the wolves howled. Edith felt the hunger stronger than she ever had before. She stared into the cherry eyes of the boy on her platter and remembered Mara; how the girl had not even lived to be sixteen before her hand was given, her belly swelled, and her person mutated into a vessel that served every purpose but her own. The wolves growled with anticipation, famished faces fixed in waiting, drool dripping down exposed fangs. Aster licked her lips ravenously, leaning over her own plate. A wolf-in-waiting hovered by Edith, cutlery ready, prepared to assist her in any way.

There was nothing left to do now. Nothing more but to eat. So, Edith opened her mouth and, with each bite, the hunger faded away.