The text of this article was read aloud and recorded for your greater accessibility and viewing pleasure:

Audio PlayerAudio voiced by Sisel Gelman and recorded and edited by Gren Bee.

What is it like being a formerly undocumented writer?

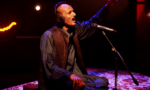

Wangeci Gitau is a formerly undocumented writer from Kenya. They identify as Black, Indigenous (they are of Kikuyu, a Bantu ethnic group that are native to Kenya’s central highlands), and queer. The intersection of all these identities inform their art practice and activism.

féi hernandez (who doesn’t use capital letters when spelling her name), is a trans formerly undocumented writer from Mexico. She is a multidisciplinary artist and writer whose work focuses on indigeneity and the undocumented experience.

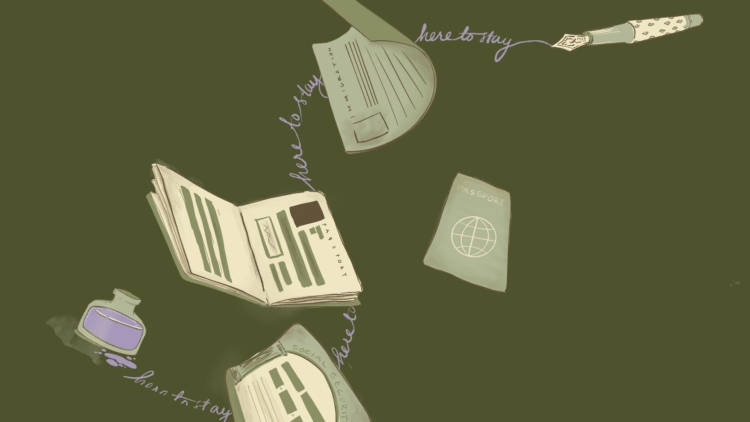

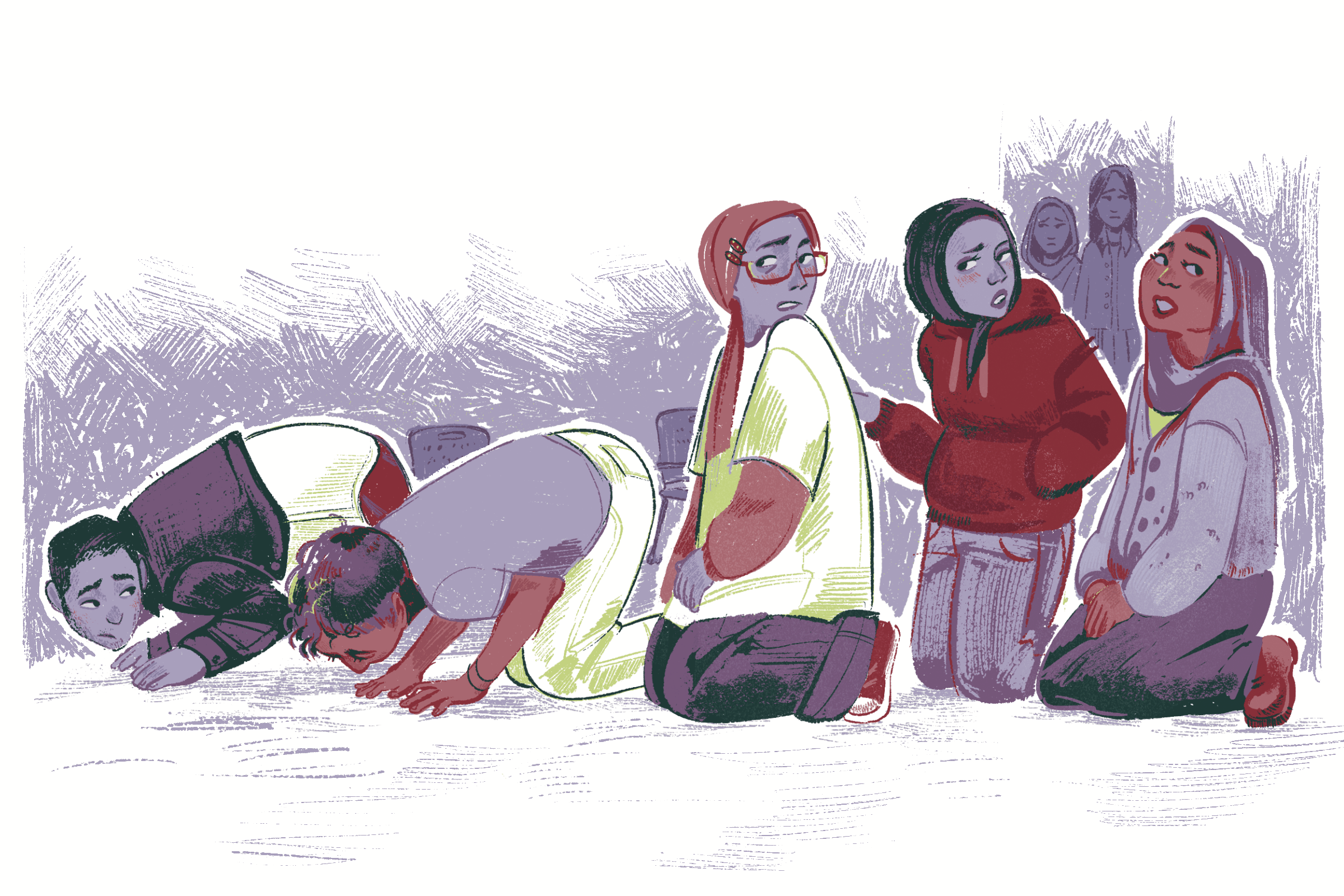

“Here to Stay” (Harper Collins 2024) by the Undocupoets is a collection of poems, streams of consciousness, and visual text-based art that accompany a personal reflection from their authors. The Undocupoets are a group of undocumented writers who mainly operate online until they activate in physical readings and workshops. They try to grapple with the dissonance of being so simultaneously visible and invisible — undocumented people receive so much visibility and critique as a targeted monolith, but the individuals themselves fall through the cracks of society. The choices of form and narrative in the Undocupoet community communicate that dissatisfaction with limitations, and yet, a need to play by the rules to survive.

Both Gitau and hernandez identified finding information on navigating their legal status as one of the most difficult aspects of being undocumented.

“Of course there is shame and stigma — both interior from yourself and exterior from the outside world — but there are also legal issues,” Gitau said. They added that people are hesitant to publicly talk about the topic in fear that they will be putting themselves or their friends at risk.

“It’s not easy, because I can’t forthright say all the things [I want to say]. So how do I write about undocumentedness, and the nooks and crannies of it, without outing myself?,” hernandez said.

There are many hardships to being an undocumented writer, said Gitau, and they range from the bureaucratic to the ideological.

“As undocumented, you can’t work. You can’t travel to see family in other countries. You can’t study at some colleges — and the colleges that do accept you are because of undocumented activists who have fought hard for that opportunity. You can’t drive because you don’t have a driver’s license. Part of the undocumented experience is seeing other people hit milestones that are barred from you,” Gitau said. They added that it is logistically difficult to find funding or payment for a writing project, or to apply for a grant, without a social security number.

“I couldn’t leave the state; I was afraid to. I was paranoid of cops. [I] became very law-abiding because I couldn’t be the reason my family got deported if I was ever caught [commiting a crime],” hernandez said.

Ideologically, Gitau touched upon the concept of how “Black Excellence” and “Migrant Excellence” — the internalized belief from the perspective of a marginalized person that they must work harder than others to prove their worth to the community — compounds with “Undocumented Excellence.”

Gitau said they have had difficulty finding marginalized writing spaces that fully understand their perspective.

“There are not a lot of stories about Indigenous African Black people in America,” they said. Their experience has been that most undocumented spaces in the United States are Latino spaces, and most of these spaces operate in Spanish. And although Gitau experiences the struggles of being Black in America, this Black space is not an undocumented space. Gitau’s compromise in navigating this is to write about being an undocumented Kikuyu in a way that resonates with people who are queer, Black American, or Latino.

“Only delusional people want to be writers, but this is magnified for undocumented people. To document the undocumented is a paradox,” Gitau said.

“I think publishing is my way of documenting the undocumented experience. I don’t give a fuck about being a literary award winner; I’m doing this for my people,” hernandez said.

hernandez considers archiving to be evidence that she and others like her are here and taking up space. There isn’t much text on undocumented individuals, so she considers it her responsibility to create that archive. She also sees the responsibility of discerning what needs to be brought into the future. What stories and histories are we taking with us?

Gitau also considers themself an archivist and spent the summer of 2024 doing research on their heritage at Oxford University.

Gitau said “Here to Stay” was an accessible way for an undocumented person to be published by one of “The Big Five” publishers. The submission process was a simple Google Form with no querying, and the writers received monetary compensation for their work.

Gitau and hernandez see art as an important place for political work. Art is the bridge between activism, creativity, critical thinking, and micro and macro experiences. What allies of undocumented people can do today is educate themselves on the topic of undocumentation and vote in support of laws proposed by undocumented people. As undocumented people in the United States cannot vote, allies hold the responsibility to magnify marginalized voices and embrace the privilege of being able to vote as a United States citizen.